INTRODUCTION

What makes for a good leader? At one level of discourse, it may appear to be a simple question, yet the literature on the subject suggests it has not been an easy one to answer. Indeed, there continue to be competing perspectives on what constitutes an effective leader. The prototypical alpha male leader is often the first leadership style that stands out—such a person is often a man who leads with an emphasis on a top-down hierarchy, independent action, and self-centeredness.1 Schein’s2,3 “think manager—think male” stereotype illuminates the tendency for people to think of masculine, agentic males when considering candidates for leadership positions. However, due to public outcry after highly publicized ethical breaches by leaders who fit the alpha male stereotype (e.g., Enron’s Kenneth Lay and Tyco’s Dennis Kozlowski), many leadership theorists are now focusing on ethical and communal styles of leadership.4,5

One influential perspective, especially in organizational psychology, is the transformational leadership theory and model.6,7 A transformational leader is one who inspires their followers to realize their fullest potential.8 While admirable in its intentions, a transformational theory of leadership has important limitations. Researchers developed the theory based upon Eurocentric notions of a charismatic leader. In fact, transformational leadership is associated with higher levels of extraversion.9 One of the problems with the theory and model is that its effectiveness depends heavily on a cultural context.10 The authors note that researchers have studied transformational leadership across cultures, and the behaviors which define it are different depending upon the cultural background of the leaders and followers. For example, they cite Bass’s11 study which demonstrates that a leader being prideful and vocal about their accomplishments is beneficial in Indonesia but looked down upon in Japan. Furthermore, transformational leadership is not only culturally specific, but it also has mixed results in multicultural environments. Even in the United States where extraversion and charisma are valued, members of ethnic minority groups may not endorse this style.12

The concern with multiculturally competent leadership is important as we strive to develop leadership ideals and practices for the future. The world will experience drastic population diversification and thus multicultural changes in the coming decades. According to Schwartz,13 humanity is now entering its third Great Transformation, the rise of revolutionary science and technology which will radically change the way our world functions and how humans exist together. The author argues that these changes are occurring because of a multitude of societal shifts happening simultaneously, such as changes in human migration patterns, advances in technological capability by orders of magnitude, and the willingness of countries to work together in solving global issues.13 He argues that these factors will render our society unrecognizable in the span of thirty years.

Population demographics will drastically change as we undergo the transformation proposed by Schwartz. The United States Census Bureau (USCB)14 predicts that by 2044 the United States population will exceed 600 million and current ethnic minorities such as Latinos, African-Americans, Asian-Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Pacific Islanders will comprise the majority population at just over 50%. This shift will mark the end of the centuries-long tradition of white, Eurocentric individuals representing the majority demographic in America, and contexts in which leadership occurs will look very different than they have in past generations.

As this change occurs, the effectiveness of homogeneous styles of leadership will continue to decline. Connerley and Pederson15 address the dangers of multiculturally incompetent leadership within such diverse populations. They explain that when a leader cannot understand the varying viewpoints of their followers, they tend to misattribute the intentions of their followers. These false assumptions cause defensive disengagement on the part of both the leader and the follower, which leads to negative workplace outcomes. Indeed, it would seem multiculturally competent leadership will be necessary to adapt and be successful in a 21st century work environment.

Avolio16 explains that authentic leadership was developed to address the multicultural limitations of promising communal leadership models like transformational leadership. According to Walumbwa and colleagues,17 authentic leadership consists of four dimensions: self-awareness, balanced information processing, relational transparency, and an internalized moral perspective. This style takes into consideration the dynamic relationships between the leaders, their followers, and the cultural situation in which the leadership is taking place.16 Researchers have found a positive relationship between authentic leadership and positive workplace outcomes around the world.18,19,20 For example, Olaniyan and Hystad21 found that employees with authentic leaders tended to be more satisfied with their jobs and less likely to quit. These results indicate that authentic leadership may be a strong option for future leaders and successful organizations in our rapidly changing world.

Furthermore, as countries become more diversified than in previous generations, it may be time to seriously consider assessing leadership styles from different parts of the world. Daoist leadership, for example, is one prime example of an Eastern leadership style that is highly communal and ethical. According to Ma and Tsui,22 Daoist leadership originates from the traditional Chinese philosophy, Dao De Jing, written by Laozi, a contemporary of the Chinese philosopher Confucius. The authors explain that while there is no explicit leadership training defined in Daoism, the Dao De Jing advises a leader to only act when necessary in positions of leadership.22 The logic behind this mandate is that people are inherently good and moral workers, but when they are ruled by an authoritative power rather than left in peace they can become “cunning thieves”.22

Leadership scholars have different ideas about the applicability of Daoist leadership in Western settings. Some have linked Daoist leadership with contemporary leadership styles, such as the laissez-faire style of leadership.22 Originally defined by Bass,23 leaders who adopt a laissez-faire style tend to be passive and avoid making important decisions in their role as a leader. Research has shown that laissez-faire leadership is ineffective in Western Euro-American societies as it is negatively correlated with follower satisfaction and the perceived effectiveness of leaders.24 Daoist leadership resembles laissez-faire leadership because the leader allows their followers to have more autonomy in decision-making, preferring to remain in the background and avoiding the use of punishment. Because of this similarity, those who view the world as a competitive and hierarchical place may discount Daoist leadership as impractical in the Western world, as they have done with laissez-faire leadership.

Lee25 proposes an alternate way of viewing Daoist Leadership by describing such leaders as highly altruistic. He argues that the teachings of Daoism encourage leaders to be “water-like,” allowing them to flexibly adapt to the needs of the situation while maintaining humility.25 Given Schwartz’s13 claims about the Great Transition humanity will undergo in the next 30 years, this type of flexible leadership seems to hold a lot of promise, as their flexibility may allow them to be more well-liked and effective in their positions. However, the characteristics and behaviors of leaders are not the only relevant factors for successful leadership. Leadership has often been defined by prevailing cultural norms, much in the same way that, as Winston Churchill allegedly claimed, history is written by the victors.26

While people commonly refer to the United States as a “melting pot,” the zeitgeist of the 20th century privileged homogeneity and “whiteness” at the expense of genuine cultural diversity.10 This pattern extended to positions of leadership, as leaders often emerge because of privileged status within society. Traditional ideals in the Western world prescribe the Eurocentric, white, heterosexual male as a beacon of what leadership should be. According to Zaccarro,27 much of this stereotype may be due to ideas put forth by late-19th century authors such as Thomas Carlyle and Francis Galton. Galton’s28 Hereditary Genius and Carlyle’s29 On Heroes and Hero-worship and the Heroic in History, depict the ideal leader as a “Great Man” who is divinely-appointed and displays stereotypically masculine traits such as aggressiveness, dominance, and assertiveness. These authors based their books’ themes on extenuated observations of history told through a masculine lens rather than empirically supported research. Nevertheless, researchers through the mid-20th century continued to study leadership by examining those who already held leadership positions, and the theories developed from this research affirmed the masculine “Great Man” stereotype of leadership.30

However, there is a disconnect between the pervasiveness of the “Great Man” stereotype of leadership and its effectiveness in practice. Research has shown that top-down authoritarian styles of leadership are much less effective than other styles.31,32 Given the lack of support for the effectiveness of top-down authoritarian styles, we are interested in why these leadership styles remain so pervasive. Avolio16 provides a possible explanation by arguing that leadership theories often focus on the leader at the expense of the people they are leading. He uses Triandis’33 description of the difference between allocentric and idiocentric followers to illustrate the difference that a follower’s personality can make in shaping their attitudes towards leaders. He describes allocentric followers as those who are focused on the good of the group above the good of the individual.33 These followers tend to prefer leaders who make decisions that are in the best interest of the group. Idiocentric followers, by contrast, are more interested in the good of the individual (themselves) over the good of the group. These followers tend to prefer leaders who make decisions that are in their own best interest.

Considering that followers rate leaders differently based on their idiocentric-allocentric orientation, our ongoing research activities have given attention to the personal characteristics of followers and how they relate to leadership style preferences. To promote effective multicultural leadership theories, we will need to better understand American citizens’ attitudes towards different leadership styles. We have chosen to focus on individual differences in follower social dominance orientation and their relationship to attitudes towards alpha male, authentic, and Daoist leaders.

Social dominance orientation refers to a person’s general desire for hierarchy between social groups and is in many ways at odds with trait agreeableness.34,35,36 Agreeable people tend to have lower levels of social dominance orientation and endorse communal values rather than competition.34 Disagreeable people, in contrast, are oriented towards social stratification and hierarchy. Interestingly, a meta-analytic literature review found that transformational leadership is closely related to authentic leadership and positively correlated with agreeableness.9 Authentic leadership and Daoist leadership both emphasize diversity and treating every member of a group equally. As people adopt more egalitarian modes of leadership (e.g., authentic, transformational, and Daoist) they seem to exhibit higher levels of agreeableness. When a disagreeable person who is high in social dominance orientation is exposed to authentic or Daoist leadership, they are confronted with a leadership style that contradicts their temperament in a manner that may not be well received. For this reason, the current study tests the ability of social dominance orientation to predict attitudes towards communal leaders.

We hypothesize that participants who are low in social dominance orientation will most prefer authentic leadership and Daoist leadership, while participants high in social dominance orientation will most prefer alpha male leadership. Furthermore, we expect that participants will prefer authentic and Daoist styles of leadership over alpha male leadership. Our aim is to contribute to the field of leadership psychology by furthering our understanding of how follower characteristics relate to attitudes towards influential leadership styles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Western Washington University (Protocol #: EX17-075). Using an Amazon Mechanical Turk sample, we collected 117 participants, each of whom we paid 80 cents for taking part in our study. The mean age of participants was 33.41, with a range from 20 to 77. Sixty-three percent of the sample identified as male, and 37% identified as female. Eighty percent of the sample identified as white, 9.4% identified as Asian-American, 7.7% identified as African-American, 2.6% identified as either mixed ethnicity or other, and 0.9% identified as Native American. Seventy-five percent (75.2%) of the sample were paid employees, 13.7% were self-employed, 6.0% were looking for work, 1.7% were retired, and 3.4% of identified as not working (other) and listed such responses as “student,” ‘homemaker,” and “stay-at-home parent.” Seven percent (7.7%) of the sample were high school graduates, 24.8% had some college but no degree, 14.5% had their Associate’s degree, 41.9% had their Bachelor’s degree, 7.7% had their Master’s degree, and 3.4% indicated having a Doctoral or professional degree.

To be eligible to take part in our study, participants had to be from the United States and have a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) acceptance rate of at least 90%. The HIT acceptance rate refers to the percentage of online tasks a worker has completed with the approval of the requester. This selection criteria assists in assuring the reliability of the survey responses. Research has shown that participants with higher HIT acceptance rates tend to pass attention check questions more frequently than participants with lower rates, and they generally provide higher quality data.37 We excluded five participants from our analyses because they took less than 2 minutes to complete the study.

We administered the survey via Qualtrics surveying site, and each participant read an informed consent form which indicated that by continuing with the survey they were giving consent for participation. After giving informed consent, each participant read a paragraph which described either a Daoist leader, an alpha male leader, or an authentic leader. We counterbalanced the order in which the descriptions were presented to participants so that each would read all three leader profiles in a randomized sequence to reduce possible order effects. Descriptions were a paragraph long and had no identifying demographic information to minimize bias towards gendered descriptions.

After reading the profile, we asked participants to rate 12 different adjectives on a 5-point Likert-type scale regarding how well each adjective described the leader whose profile they had just read relative to the other adjectives. The response options ranged from 1(One of the best) to 5(One of the worst).Next, participants rated how likable and competent they found the leader from the profile they had just read. The likability scale ranged from 1(Very Unlikable) to 5(Very Likable), while the competence scale ranged from 1(Very Incompetent) to 5(Very Competent). After reading the first leader description and rating the adjectives as well as the likability and competence of that leader, participants repeated those steps for the other two leadership styles.

Next, we presented participants with all three of the leader descriptions and prompted them to rank the leaders based on who they would most want to follow. We then asked participants two open-ended questions about why they chose the profiles they most preferred and least preferred respectively. After this, participants completed the Social Dominance Orientation Scale Short Form (α=0.93).35 This scale measures a person’s general endorsement of inequality between social groups. The scale prompts participants to rate the degree to which they favor or oppose eight different statements. A representative scale item states, “We should work to give all groups an equal chance to succeed.” Response options ranged from 1(Strongly Oppose) to 7(Strongly Favor). Finally, participants answered demographic questions and read a debriefing statement.

RESULTS

We examined whether followers view authentic leadership as viable. Furthermore, we investigated the relationship between attitudes towards communal leaders and follower characteristics. Unfortunately, our sample lacked variability with regard to ethnicity such that any analyses we conducted using ethnicity were generally uninformative. However, we were able to conduct several exploratory analyses. These analyses provide insight into the relationship between gender, social dominance orientation, and leader preferences.

What is the relationship between follower’s level of social dominance orientation and their attitudes towards communal leaders?

Using SPSS 24, we examined the bivariate correlations among social dominance orientation and the reported likability and competence of each leader. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations and Table 2 for bivariate correlations. Social dominance orientation had a negative relationship with ratings of the authentic leader’s competence. Participants’ ratings of the Daoist leader’s competence had a near statistically significant negative relationship with social dominance orientation. Also, we found a positive correlation between social dominance orientation and competence ratings of the alpha male leader. The data indicate that high social dominance orientation is linked to perceiving communal leaders as less competent than alpha male leaders.

| Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Social Dominance Orientation and Leader Likability and Competence Ratings (N=117) |

| Variable |

M |

SD |

| 1. Social dominance orientation |

2.59 |

1.56 |

| 2. Authentic leader likability |

4.11 |

0.84 |

| 3. Authentic leader competence |

4.15 |

0.72 |

| 4. Daoist leader likability |

4.07 |

0.83 |

| 5. Daoist leader competence |

3.68 |

0.90 |

| 6. Alpha male leader likability |

2.63 |

1.19 |

| 7. Alpha male leader competence |

3.68 |

1.06 |

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations Between Social Dominance Orientation and Leader Likability and Competence

Ratings (N=117) |

| Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| 1. Social dominance orientation |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Authentic leader likability |

-.15 |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Authentic leader competence |

-.29** |

.60*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

| 4. Daoist leader likability |

-.19* |

.29** |

.28** |

– |

|

|

|

| 5. Daoist leader competence |

-.18+ |

.14 |

.27** |

.49*** |

– |

|

|

| 6. Alpha male leader likability |

.44*** |

-.07 |

-.16+ |

-.19* |

-.19* |

– |

|

| 7. Alpha male leader competence |

.20* |

.17+ |

.12 |

-.03 |

-.10 |

.48*** |

– |

| +p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; two-tailed. |

Daoist leader likability was negatively related to social dominance orientation and unrelated to reports of authentic leader likability. Social dominance orientation was positively related to alpha male leader likability. In fact, social dominance orientation explains nearly 20% of the variance in alpha male leader likability. Those with high social dominance orientation seem to find alpha male leaders more likable than communal leaders. In sum, participant’s level of social dominance orientation tended to be negatively associated with their perceptions of communal leader’s likability and competence.

Do followers view authentic leadership as viable when compared to other prevalent leadership styles?

We asked participants to rank the three leadership styles from most preferred to least preferred. Using this ranking system, we were able to assess participants’ preferences for authentic leaders relative to other prevalent leadership styles. We conducted a one-way chi-square test comparing the frequency with which each leadership style was ranked most preferred. Results indicated a statistically significant difference in participants’ ranking of each leadership style as most preferred, X2(2)=28.62, p<.001. The Daoist leader was ranked number one most frequently (n=57), followed by the authentic leader (n=38), and the alpha male leader (n=12). Having assessed which leadership styles are most preferred, we then examined the ones that are least preferred.

We performed a one-way chi-square on the frequency with which participants ranked each leadership style least preferred. The data indicated a statistically significant difference regarding the leadership style participants least preferred, X2(2)=34.11, p<.001. Alpha male leaders were ranked least preferred most often (n=64), followed by authentic leaders (n=24), and finally Daoist leaders (n=19). Both chi-square tests converge on the idea that authentic leadership is more preferred than alpha male leadership but less preferred than Daoist leadership.

To examine participants’ attitudes towards multiculturally competent leaders, we compared the likability and competence ratings of authentic leaders to the other leadership styles. A within-subjects t-test revealed that the mean likability of authentic leaders was greater than the mean likability of alpha male leaders, t(116)=10.66, p<.001, d=.99. There was no difference between the mean likability of authentic leaders and the mean likability of Daoist leaders, t(116)=.47, p>.05, d=.04. The mean competence rating of authentic leaders was greater than the mean competence rating of Daoist leaders, t(116)=5.24, p<.001, d=.48, and alpha male leaders, t(116)=4.21, p<.001, d=.39. Authentic leaders were rated as most competent when compared to Daoist and alpha male leadership styles. Participants viewed authentic leaders as more likable than alpha male leaders, but not Daoist leaders.

What is the relationship between social dominance orientation, gender, and attitudes toward communal leaders/alpha male leaders?

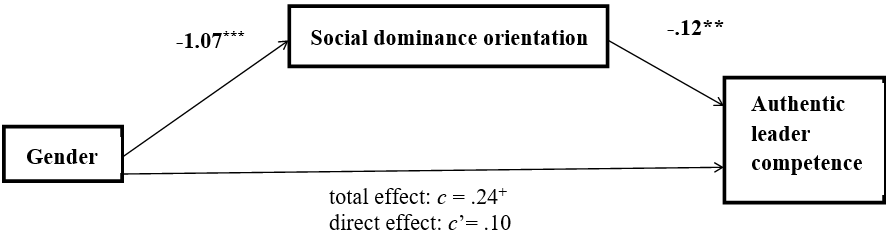

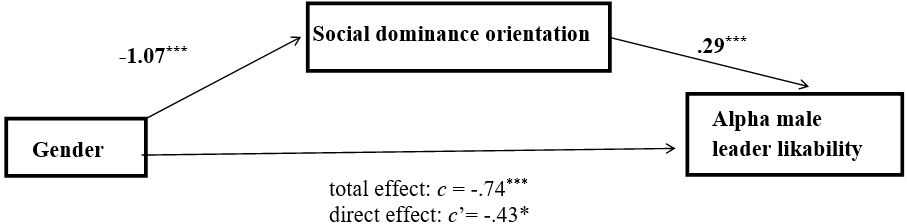

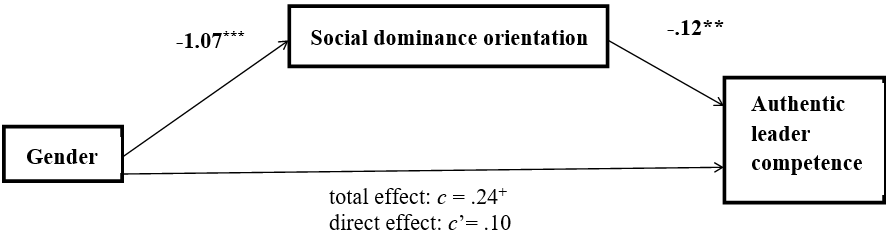

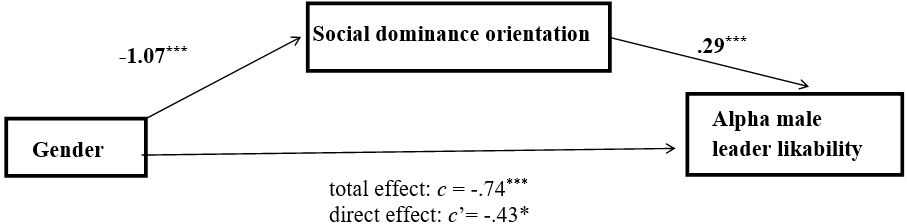

In a series of exploratory analyses, we investigated the role of social dominance orientation as a mediator of the relationship between gender and attitudes towards alpha male/ communal leaders. We conducted our analyses using the Hayes’38 PROCESS macros (Model 4). We chose to have indirect effects bootstrapped 5000 times and dummy coded gender such that a score of 1 indicated male and 2 indicated female. In our first model, the independent variable was gender, the mediator was social dominance orientation, and the dependent variable was authentic leader competence ratings. That is, we tested whether gender exerts its effect on authentic leader competence ratings through social dominance orientation. Figures 1 and 2 depict the mediation models that follow using unstandardized regression coefficients.

Figure 1. Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for Social Dominance Orientation Mediating the Relationship between Gender and Authentic Leader Competence Ratings

Gender is Dummy Coded such that 1 Indicates Male and 2 Indicates Female. +p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Figure 2. Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for Social Dominance Orientation Mediating the Relationship between Gender and Alpha Male Leader Likeability Ratings.

Gender is Dummy Coded such that 1 Indicates Male and 2 Indicates Female. +p<.10; * p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Gender was a positive predictor of social dominance orientation, b=-1.07, SE=.28, p<.001. Furthermore, gender was a near statistically significant positive predictor of authentic leader competence ratings, b=.24, SE=.14, p<.10. That is, participants identified as female tended to find the authentic leader more competent when compared to men. When we controlled for social dominance orientation, gender was no longer a near statistically significant predictor of authentic leader competence ratings, b=.10, SE=.14, p>.40. These findings are consistent with the idea that social dominance orientation fully mediates the relationship between gender and perceptions of authentic leader’s competence. The combination of gender and social dominance orientation explained 9% of the variance in authentic leader competence ratings, F(2,114)=5.54, MSE=.47, p<.01, R2=.09. A Sobel test indicated a small positive indirect effect of gender on authentic leader competence ratings, b=.13, SE=.06, Z=2.21, p<.05. Identifying as female predicted lower levels of social dominance orientation when compared to identifying as male which, in turn, predicted perceiving authentic leaders as more competent.

In our second model, we tested whether social dominance orientation mediated the relationship between gender and ratings of alpha male leader’s likability. Gender had a statistically significant negative effect on alpha male leader likability ratings such that women tended to dislike alpha male leaders more than men, b=-.74, SE=.22, p<.001. When we controlled for social dominance orientation, gender remained a statistically significant predictor of alpha male leader likability, b=-.43, SE=.22, p<.05. These findings suggest that social dominance orientation partially mediates the relationship between gender and alpha male leader likability. The combination of gender and social dominance orientation explained 22% of the variance in alpha male leader likability, F(2,114)=16.25, MSE=1.11, p<.001, R2=.22. Using a Sobel test we found that gender had a small negative indirect effect on alpha male leader likability, b=-.31, SE=.11, Z=-2.81, p<.01. In other words, identifying as female predicted lower levels of social dominance orientation when compared to identifying as male which, in turn, predicted perceiving alpha male leaders as less likable.

Finally, we noticed that some participants displayed a gender bias in their qualitative responses; they assumed the leaders they read about were male despite the profiles being gender-less. For example, when asked why they chose the leader that they ranked #1, one participant said, “He inspires people to do well. He is open-minded and strong and respectful of differences.” When asked why they chose the leader they ranked #3, another participant said, “I think this leader would put succeeding in a competition over his group members.” These gender-biased responses were present in 19 out of 117 participants (16.24%). Interestingly, no participant displayed a gender bias in the opposite direction by assuming that the leader was female.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to further our understanding of American citizens’ leadership preferences and how those preferences relate to the personal characteristics of followers. We hypothesized that participants would prefer communal leaders to alpha male leaders due to their emphasis on diversity and relationship-building. We further hypothesized that authentic leadership would be the most preferred style because of its unique strengths when compared with Daoist leaders and alpha male leaders. While prior research tended to focus on the personal characteristics of leaders,39,40 the current study focused on the personal characteristics of followers. That is, we adopted an individual difference perspective regarding how followers perceive leaders.41

The data support our hypothesis that participants prefer communal leaders to alpha male leaders. The greatest number of participants ranked the alpha male leader as least preferred, and the least participants ranked the alpha male leader as most preferred. Furthermore, participants ranked the alpha male leader statistically significantly lower than the authentic leader in likability and competence. Surprisingly, the Daoist leader was the most preferred style according to participant rankings, receiving the most preferred ranking by the most participants and the least preferred ranking by the least participants.

One possibility is that participants prefer the Daoist leaders because of their ability to promote trust and cooperation.42 However, participants rated authentic leaders as statistically significantly higher than both Daoist leaders and alpha male leaders on competence. These ratings suggest that participants notice the unique competencies of authentic leaders such that authentic leadership may still be most beneficial overall. This perception of authentic leaders as highly competent may be due to their effectiveness in leader-member exchanges, which predict positive leadership outcomes.43 Furthermore, authentic leaders express multicultural competence by creating inclusive environments where employees feel comfortable expressing their opinions.44 Finally, authentic leaders display a great deal of emotional intelligence, especially in the dimension of self-awareness.45 A combination of these factors may be contributing to the competence of authentic leaders above Daoist leaders.

We examined how social dominance orientation relates to evaluations of alpha male, Daoist, and authentic leaders. In accordance with our hypotheses, individuals with dominant and anti-egalitarian tendencies,35 were less likely to rate authentic leaders as competent. Followers with higher levels of social dominance orientation may be less likely to appreciate the multicultural competencies of authentic leaders. In subsequent exploratory analyses, we found that identifying as female predicted lower levels of social dominance orientation which, in turn, predicted more positive attitudes towards authentic leaders and more negative attitudes towards alpha male leaders. The gender difference in social dominance orientation is consistent with some prior research46; however, there remains debate regarding why such gender differences exist.47 Our analyses indicate that gender differences in social dominance orientation are important predictors of follower’s attitudes towards alpha male and authentic leaders.

CONCLUSION

One limitation of the current study is that it was correlational such that we are unable to make causal claims. Future research should consider experimentally manipulating social dominance orientation (see Huang & Liu48 for priming paradigm) and then assess its impact on follower’s attitudes towards authentic leaders. Given that some participants exhibited a gender bias in their qualitative responses, the effect of adding gender to hypothetical leadership profiles would constitute a valuable contribution to existing literature.

Our sample was unrepresentative of the population in terms of gender, ethnicity, and education. For example, our sample over-represented men and was more educated when compared to the national average.49,50 Future research may utilize quota sampling techniques to ensure a representative sample on these dimensions. A study investigating the influence of follower ethnicity on leadership preferences seems essential given the importance of multiculturally competent leadership. However, it is important not to conflate ethnicity with cultural identity when surveying members of a single population with different ethnicities. Given our research questions, an analysis of ethnicity went beyond the scope of our study. Future studies exploring the relationship between leadership preferences and ethnicity would benefit from asking participants questions about their cultural identity.

Additionally, we used single-item measures for the likability and competence of each leader that may have questionable reliability. Future research may use multi-item measures of likability and competence that more fully capture people’s attitudes towards communal leaders.

Ultimately, the potential of authentic leadership will only be realized if followers view communal leadership as viable. The current study advanced an individual difference approach to understanding follower’s attitudes towards leaders. Understanding why certain members of society are reluctant to endorse authentic leadership is a pivotal part of breaking down barriers for communal leaders in the coming years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The corresponding author Dr. Joseph Trimble received a $500 faculty research grant which funded this research from the Department of Psychology at Western Washington University Bellingham, WA, USA.

We received Institutional Review Board approval from Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA, USA, on May 25, 2017. (Protocol #: EX17-075).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors further declare that they have no conflicts of interest.