INTRODUCTION

Early-onset scoliosis is an umbrella term coined to describe any form of scoliosis that starts before ten years of age.1 The first decade of life is characterized by significant growth and development in body organs and functions. Abnormal spinal curvatures at this critical age may adversely impact the growth and expansion of the thoracic cage and the lungs, as the growth of both is interdependent. There is mounting evidence suggesting that patients who develop scoliosis before ten years of age are at increased risk of developing respiratory failure secondary to thoracic insufficiency syndrome, the inability of the thorax to support normal lung growth and development.2,3,4,5 In other words, treating early-onset scoliosis transcends correcting the aesthetic part of the deformity to preserving lung development and improving patients’ survival.

Both conservative and operative measures are used to treat early-onset scoliosis. Physicians often resolve to bracing, serial casting, and even traction to postpone or sometimes obviate the need for more aggressive surgeries. If done at such young ages, traditional fusion surgery might lead to undesirable consequences ranging from failure to halt curve progression to severely stunting growth.6 All in all, neither conservative means nor fusion surgery is flawless, with each having its trade-offs and drawbacks.

Recently, significant momentum has been seen in using what is now called growth-friendly implants.7 These devices offer the opportunity to treat spinal deformity while maximizing growth potential and thoracic expansion at the same time. Based on the forces exerted by these implants on the thoracic cage and vertebral column, three systems have been recognized8 :

1. Distraction-based systems like growing rods and vertical expandable prosthetic titanium ribs (VEPTR).

2. Compression-based systems like staplers and spinal tethers.

3. Guided growth systems like Shilla and Luque trolley.

Whether used as single or dual constructs, conventional growing rods have shown that they can curb spinal deformity progression, proving to be a useful delaying tactic for spinal fusion in patients with early-onset scoliosis.9 Occasionally, this effect can be so dramatic, obviating the need for fusion surgeries altogether.

However, the need for sequential lengthening surgeries can remarkably add to the physiological, psychological, and aesthetic burdens that patients with early-onset scoliosis must go through.10,11 Consequently, magnetically controlled growing rods were introduced as a means of providing growing implants with less frequent lengthening procedures.

Magnetically controlled growing rods, widely known as MAGEC after the implant produced by NuVasive®, are placed in a similar manner to conventional growing rods. They are composed of titanium rods with a middle telescoping part that can be periodically expanded by an external remote controller. With the advent of magnetically controlled rods, many of the comorbidities associated with conventional devices were lessened. On the other hand, unfamiliar problems were introduced with these novel devices.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 8-year-old girl was diagnosed with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hips during infancy and underwent multiple hip surgeries to correct her hip problems. At the age of four, she was diagnosed with scoliosis in another hospital and referred to our institution for further management after failing conservative management in the form of bracing. The chief complaint was the presence of spinal deformity with a left thoracic hump. Her developmental examination findings were appropriate for her age. The neurologic exam showed normal motor and sensory functions. No significant abnormalities or deficits were noticed.

Radiographs including anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral standing spine X-rays were ordered. They showed a left thoracic curve with a Cobb angle of 88 degrees measured between T3 and L1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scoliosis X-Ray of the Patients Showed that Cobb Angle of 88° Measured between T3 and L1

Due to the early onset of scoliosis and the presence of left thoracic curve, an MRI study was ordered. It showed no tethered cord nor vertebral abnormalities.

A decision was made to proceed with a growth-friendly implant, magnetic expandable rods, to control her curve progression. Dual 4.5 rods were inserted, with the proximal foundation being at the T3-4 level and the distal one at L2-3. Both rods were secured in the submuscular/subfascial plane. The procedure was uneventful. The postoperative x-ray showed a well-seated system. The Cobb angle measured 38° (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Post-Operative X-Ray Showed a Well-Seated System.

The Cobb Angle Measured 38°

Four-months after the index surgery, her first elongation was attempted. The magnetic gear was expanded by 4 mm. Three months after that, she underwent another successful elongation. The Cobb angle was 48°, and 9 mm were added in length (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Post Elongation X-Ray Showed the Magnetic Gear was Expanded by 4 mm

However, three subsequent elongation attempts failed, with (Figure 4) depicting the latest. After discussing the case with the parents, a decision was made to exchange the rods with conventional ones using the same foundations. A month later, the conventional rods were inserted (Figure 5).

Figure 4. X-Ray After Three Subsequent Attempts for Elongation

Failed, and the Gear Lost Elongation

Figure 5. X-Ray Showed the Exchange of MEGEC System with Conventional System

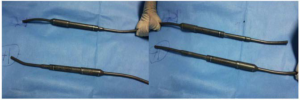

We evaluated the rods after removal. Both magnet gears had failed. We found that the rods could be elongated and shortened manually with no force. They could not maintain expansion in the telescoping movement. We called this a catastrophic failure (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The MAGEC Rods Could Not Maintain Expansion and Both have Telescoping Movement., We Named that Catastrophic Failure

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Early-onset scoliosis represents a group of conditions that cause scoliosis before ten-years of age regardless of the etiology. Four main etiologic categories have been described: congenital, neuromuscular, syndromic, and idiopathic.6 These are grouped together because they all carry the risk of developing thoracic insufficiency syndrome. Early-onset scoliosis represents a management conundrum for physicians and families alike. Management options are diverse, ranging from conservative to operative, with most carrying the same goal, delaying or avoiding fusion surgery until ten years of age or older.

Observation is usually the only management that is needed for curves less than 20°. Serial casting can be used for patients with curves larger than 20°. Mehta et al showed that serial casting could be a definitive treatment option for patients with idiopathic curves if started before two years of age.12 Bracing can also be perused as a delaying measure, but problems with compliance and secondary sagittal plane deformities have been reported. Halo gravity traction has been used to treat early-onset scoliosis.

Great interest has been seen in using growth-friendly implants such as conventional growing rods. Growing rods are commonly used for early onset scoliosis (EOSTM) as they have the advantage of correcting the deformity while allowing the spine to grow. However, the need for frequent lengthening surgeries has never been a pleasant occurrence to the patient, their family, or the physician, with each subsequent surgery carrying an increased medical, financial, and psychological burden of its own.

Magnetic expandable rods managed to overcome the issue of multiple surgeries by providing a device that can be elongated in the clinic by an external remote controller. It looks like a promising technology with many reporting good outcomes.13 Disadvantages, however, including costs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compatibility, are not fully explored.14 Akbarnia et al. Reported loss of initial height in three patients after the initial surgery and loss of distraction in 11 out of 68 cases. Nonetheless, the loss of height was regained and maintained after subsequent distraction precluding the need for exchanging the rods.

In our case, distraction was achieved in the first and second attempts but not thereafter. Fifty percent (50%) of the length achieved was lost in the next three months and never regained. Distraction under sedation and general anesthesia were tried but to no avail. No explanation was found for such failure. After exchanging the rods, we found that the telescoping mechanism had failed, a complication we dubbed a catastrophic failure.

Catastrophic failure has never been reported or mentioned in the magnetic expandable rod user manual. Physicians need to pay attention to catastrophic failure as it should always be considered when these types of rods lose their initial distraction without being able to regain it anymore.

In conclusion, magnetic expandable rods are a promising technology that allows spinal growth while correcting the deformity. Nevertheless, more attention should be paid to investigating these novel implants regarding their potential complications.

CONSENT

The authors have received written informed consent from the patient.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.