INTRODUCTION

Meat derived from wildlife has very significant traditional, economic, medicinal and cultural values to the indigenous people in diverse geo-ecological environments especially in tropical African rain forest terrains.1 The commercial value of bushmeat is being felt everywhere. Bushmeat has a very sentimental and closely guarded social meaning as it is the most appreciated gift rural travelers and visitors offer relatives.2

Some of the wild animals often eaten in West Africa are monkeys, baboons, deer, rats, bats, ground pigs, antelopes, squirrels, gorillas and chimpanzees.3 These animals are considered to have medicinal value and others such as baboons and chimpanzees are believed to transfer their strength and qualities to the humans who eat meat from them.4 The commercialization of traditional wildlife hunting has evolved largely due to rural urban migration, population growth and general economic transformation.5

The rate of wild animal hunting especially of large vertebrates is unstainable. The recent public outcry in Zimbabwe and America over the killing of the famous lion, Cecil for hunting trophies is living testimony of the value put on wild animal and bushmeat artifacts.6 The large-scale wanton harvesting of wildlife has resulted in some species being endangered and leading to extinction of others.6

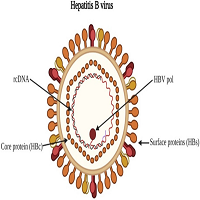

The Ebola disease outbreak in West Africa has been the largest in the history of the disease since the first case in 1976.7 The index cases in the neighboring Mano river states of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone have not been conclusively determined. Circumstantial evidence points to the source of the current outbreak to physical contact with secretions from wild fruit bats and not actual consumption of meat of the suspected reservoir or infected animal.8 The commonest mode of transmission of Ebola disease is through person to person contact.9 Social mobilization and communication has however focused on banning consumption of wild meat instead of breaking the chain of transmission from human-to-human.10

he first epicentres of the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone were in the Eastern Regional area districts of Kailahun and Kenema. These two districts are bordering Guinea and Liberia. The first two Ebola treatment centers were also established in these two districts. Kailahun district is predominantly inhabited by the Mende and the Kissi communities sharing borders with Guinea and Liberia.

METHODS

The study was conducted between June and August 2014. Different research sites, participant populations and methods for data collection and analysis were used. The ethnographic data collection methods consisted of observation of practices associated to risk of Ebola infection and prevention. For example, we carried out observation of bushmeat markets with a focus on meat processing involving human contact with blood and fluids from a diverse range of wild animals.

STUDY POPULATIONS

In the Kissi community, research was conducted in the chiefdoms of Kissi Kana, Kissi Teng and Kissi Tongi, with a more in-depth focus on the villages of Koindu and Foindu. The urban sites focused on were Kailahun city and the suburban communities living around the Ebola treatment center. In Kenema district, investigations followed the pattern of the predominantly urban trend of the Ebola outbreak. We focused on the most affected neighborhood, that of Nyandeyama, and on the town center.

For validity and exhaustiveness-related stakes, we have combined several data collection methods, including those of ethnography, qualitative interviews and in-depth case studies. We also carried out observation of the use of the devices of chlorinated water buckets in rural communities. In urban settings, we also carried out observation of the search for suspected cases as well as of collection and transportation of the dead.

Qualitative data collection was based on informal and in-depth interviews and focus-group discussions. In-depth ethnographic case study investigation was conducted in 2 settings; the village of Njala representing the rural area, and the neighborhood of Nyandeyama representing the urban settings. The case studies consisted of taking the first documented case and following all the cases related to it, with a special emphasis on chronology and social link identification.

Key informants and focus-group participants were selected from among the following populations with numbers in brackets:

• Paramount chiefs, the section and village chiefs, and the elderly male heads of households (7)

• Women traditional leaders: female senior household members, the mammy queens, the female senior members of initiation societies (10)

• The “ordinary” female household members; adult and young women (10)

• The “ordinary” male household members; adult and young men (8)

• Children of both sexes (11)

• Religion leaders; Muslim imams, Christian pastors, catholic priests (9)

• Members of modern women’s organizations, women’s church organizations, women’s NGOs and women’s formal and informal community networks (11)

• Motorbike drivers (15)

• Musicians (3)

• Herbalists and traditional healers (7)

• Blacksmiths and traditional hunters (6)

• Teachers (8)

• Market vendors (6)

• Restaurant and hotel employees, managers and waiters (10)

• Health workers (nurses, physicians and ambulance drivers and members of burial teams, health supervisors and councilors (10)

• Mob in street protest during the Kailahun street demonstration (9).

RESULTS

One hundred and fifty participants played a part in the study. Bushmeat had very significant social meaning as it was perceived to be the most appreciated gift rural travelers and visitors offered to their urban hosts. In locations where the research was conducted, the theme of bushmeat appeared most recurrent. According to medical authorities, the same bushmeat was recognized as the cause of the deadly disease. This interpretation justified the closure of bushmeat markets, as was the case in Kailahun. Unprecedented community resistance characterized by wanton widespread destruction of public property targeting health provision followed the pronouncement.

The researchers found a bushmeat market that was still operating in Kenema in spite of the total ban and also witnessed arrival of a large stock consignment of game intended for sale and consumption in the town of Daru. Observations carried out in Kenema as in Daru clearly showed that women were exposed to blood and other fluids from wild animals while processing bushmeat. Some of the animals from which the bushmeat was harvested included chimpanzees, monkeys, antelopes and wild fruit bats.

These investigations revealed that very often there was no distinction made between contact with fluids from wild animals while processing and eating bushmeat, even cooked. This made it difficult to articulate the cause and effect relationships that would guide targeted intervention.

There were certain details and clarifications to be shared with community members especially their opinion leaders on the biological reasoning that led to incriminating contact with wild animals’ fluids and spread of the infection. One participant had this to glorify the use of use bushmeat “Bushmeat or wild animals are more pure than domestic animals, because God is the one who is taking care of them. Bushmeat is sweet. It has more taste than domestic animal’s meat and is less expensive”.

DISCUSSION

A total ban on consumption of all bushmeat was put in place in Sierra Leone especially in the initial epicentres of Kailahun and Kenemaas means to break the chain of transmission of the disease. The communities studied questioned the justification and timing of total ban of business and consumption of bushmeat which have been the foundation of their livelihoods. The major transmission routes of the disease are through human-to-human through body secretions and especially through handling the dead during burials. Prevention messages emphasized wild animals as being the major cause instead of a more detailed explanation of how contact with fluids and blood may have led to catching the disease; such an explanation would certainly have led to a broader understanding and to prevention measures being taken by the people themselves.

The open-ended banning of the ubiquitous business in bushmeat without engagement of the community leaders about the inevitable change in the prevailing traditional and cultural practices was bound to be faced with community resistance which could have manifested in a variety of ways. In this case resistance was profound with wanton destruction of property.

In reality, this ban was a risky approach that was applied instead of giving all the necessary information to the communities and to trust their ability to agree on safeguards. May be at this level, feasibility of a package of measures that would have been acceptable from a biomedical point of view could have been looked at, as it would have relied on rules of hygiene, the use of gloves and other protection and education means to avoid contact with fluids and blood from those animals in question.11

The very existence and survival of rural lineage and family is being threatened for posterity through the open-ended implementation of the ban.2 In other words, reflection on the issue of bushmeat gift abandonment could be a pretext to talk about the Ebola virus and renew the concept of family continuity between city and rural backgrounds.12

In any case, it seemed urgent to bring together vendors of bushmeat (in Kenema, most of them were women) and the women who took care of its processing in the households, to adopt the most appropriate range of prevention measures. In Kailahun, an almost general opinion was that the public expected a return of mass consumption of bushmeat as soon as the Ebola outbreak was over. The return of the outbreak, due to the renewal of the risk of animal to human transmission, did not seem to be envisioned. This theme should definitely be the subject of songs and other awareness making tools likely to renew attitudes of vigilance needed to fight against the epidemic’s return, if it proved possible to currently get it under control.

Moreover, communication about bushmeat often proved to be misleading. Little importance was attached to human-to-human transmission on this occasion, so that those who did not consume bushmeat might have felt less at risk of catching the disease even if exposed to symptomatic Ebola infected patients. In some cases those who consumed bushmeat were stigmatized against whereas the main mode of transmission was definitely the one between humans. It would surely have been wise to distinguish in the prevention messages the two modes of transmission chronologically and in terms of their magnitude.

Finally, sensitization taking into account the abovementioned precautions, though it must have emphasized transmission from animals to humans, should certainly also have addressed the issue of the ecological dangers of human pressure on the natural environment. Here, the traditional concepts of sacred forest and sacred wild animals could have been incorporated, to emphasize the need to reduce human pressure on wild life.13,14

In Kailahun, the story went that the Ebola outbreak was preceded by the death of a famous ape killed by a hunter. Here, it was not only the contact with wild animal’s meat, blood or fluids that posed problem. It was the very act of killing them that posed a danger to humans. Outreach workers should organize meetings to initiate a dynamic of community consultation and debates between women vendors and women involved in bushmeat processing.

Anthropological research should be conducted to study possibilities of relapse, so that watch can be kept on such possibilities through the adoption by communities of measures to prevent the Ebola virus transmission from animals to humans.

CONSENT

All participants consented to the assessment.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.