INTRODUCTION

Examination of the small bowel lesions represents a great challenge for gastroenterologist due to its length and inaccessibility using natural orifices. It is the only part of the gastrointestinal tract that is not accessible by non-surgical endoscopy. On the other hand, radiological techniques are relatively insensitive for diminutive, flat infiltrative or inflammatory lesions of the small bowel.1,2,3

As currently available diagnostic methods are far from satisfactory results regarding diagnostic yields, patient comfort and technical ease. The video capsular endoscopy has been developed to allow direct examination of this inaccessible part of the gastrointestinal track in a safe, non-invasive and well-tolerated manner making it superior to the conventional methods, with minimal limitations in the presence of small bowel strictures or obstruction.4

Capsule endoscopy is mainly indicated for the evaluation of SB diseases, particularly for the diagnosis of OGIB. CE can be used in a variety of conditions including Crohn’s Disease (CD), malabsorption, chronic diarrhea, and evaluation of refractory iron deficiency anemia, abdominal pain, polyposis syndromes, celiac disease, and detection of small bowel tumors. Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD) is a rare additional indication.

The main risk of CE is capsular retention. The rate of capsule retention varies widely; depending almost on the clinical indications for CE, and ranges from 0% in healthy subjects, to 1.5% in patients with OGIB, to 5% in patients with suspected Chron’s disease5 and 21% in patients with intestinal obstruction.6 Therefore, CE is contraindicated in patients with known strictures or swallowing disorders.

Currently used capsular endoscopy lack the ability to obtain tissue biopsy or provide endoscopic treatment. But the near future foreshadows capsules able to pass actively through the whole gastrointestinal track, to retrieve views from all organs and to reform drug delivery and tissue sampling.7,8,9

The quality of a CE study was found to be largely dependent upon capsular transit time through the stomach and small bowel. In capsular endoscopic procedure, capsule does not always reach the cecum within battery life in 20-25% of cases.10 Long gastric transit time has been associated with failure of CE to reach the cecum. Positioning the patient in lateral decubitus and placement of CE in duodenum using endoscope are some of the methods tried to reduce gastric time.11

This study was conducted to assess the indications, findings, and complications of CE among these patients. It was done to assess the diagnostic yield of the capsule endoscopy and the complications that may occur in such patients. And to evaluate the effect of small bowel transit time on the diagnostic yield of the capsule endoscopy and assess whether longer gastric transit time would decrease the rate of complete examination of the small bowel.

METHODOLOGY

We analysed the clinical experience of the MiRo CE in 119 patients with suspected small bowel diseases in the department of gastroenterology at ibn-sina and Fedail Hospitals in Sudan, during the period from January 2010 to June 2011. It is a retrospective and prospective study – the data of the patients underwent capsule taken either from the hospital records or from the patients performing capsule endoscopy.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data was analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The small bowel transit time of all patients was subdivided to 3 group analyzed to compare the diagnostic yield, P value less than 0.05 was consider as significant.

RESULTS

One hundred nineteen patients, 69 male and 50 female were enrolled. The main indication for capsule endoscopy was OGIB, the CE identified the cause of bleeding in 39 of the 61 patients (63.9%) presented with obscure GI bleeding and Angiodysplasia was the main finding in such patients comprising 31.1%. Other indications for CE were small bowel diarrhea in 21 patients (17.6%), evaluation of Crohn’s disease in 5 patients (4.2), chronic abdominal pain in 18 patients (17.6%), non-responding celiac disease in 3 patients (2.5%) and 4 patients presented with suspicion of small bowel malignancy (Table 1).

| Table 1: Indication for capsular endoscopy and diagnosis cross tabulation. |

|

|

Diagnosis |

Total |

|

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

Normal |

Angiodysplasia |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Celiac disease |

Tumours |

Worms |

Ulcers/erosions |

Others |

| OGIB |

Count |

22 |

19 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

9 |

3 |

61 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

36.1% |

31.1% |

6.6% |

1.6% |

3.3% |

1.6% |

14.8% |

4.9% |

100.0% |

| IBD |

Count |

1 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

20.0% |

.0% |

80.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

100.0% |

Chronic

abdominal pain |

Count |

9 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

18 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

50.0% |

11.1% |

.0% |

16.7% |

.0% |

.0% |

22.2% |

.0% |

100.0% |

| Small bowel diarrhea |

Count |

4 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

21 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

19.0% |

.0% |

23.8% |

23.8% |

14.3% |

9.5% |

.0% |

9.5% |

100.0% |

| Non responding celiac disease |

Count |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

33.3% |

.0% |

.0% |

33.3% |

33.3% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

100.0% |

| Suspicion of small bowel tumour |

Count |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

25.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

75.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

100.0% |

| Others,specify |

Count |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

7 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

42.9% |

.0% |

14.3% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

.0% |

42.9% |

100.0% |

| Total |

Count |

41 |

21 |

14 |

10 |

9 |

3 |

13 |

8 |

119 |

| % within

Indication for capsular endoscopy |

34.5% |

17.6% |

11.8% |

8.4% |

7.6% |

2.5% |

10.9% |

6.7% |

100.0% |

In our study angiodysplasia constitute 31.1%, malignancy 3.3%, inflammatory bowel disease 6.6% in addition to 14.8% diagnosed as ulcers and erosions.1.6% with worms and 1.6% with Celiac disease. Gastrointestinal tumors were identified in 9 patients (7.6%). Of those, two patients were examined for OGIB, the other seven patients were examined for non-bleeding indications. The types of tumors diagnosed included two Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), three carcinoids, one adenocarcinoma, one gastric lymphoma and the histopathology was not available for two patients.

Capsule endoscopy was indicated in twenty one patients presenting with small bowel diarrhea. Of those a young 28 years old female presenting with alopecia, onchyodystrophy and small bowel diarrhea was diagnosed as Cronkhite – Canada syndrome based on CE finding together with the high clinical suspicion of her treating doctor. The CE revealed multiple jejunum and ileum polyps with a prominent big ampulla of vater.

In another young patient presenting with small bowel diarrhea and fever, colonoscopy showed cecal and descending colonic lesions, but the histopathology was not conclusive. Together with the terminal ilial lesions revealed by CE, tuberculosis was suspected. The patient responded well to antituberculous.

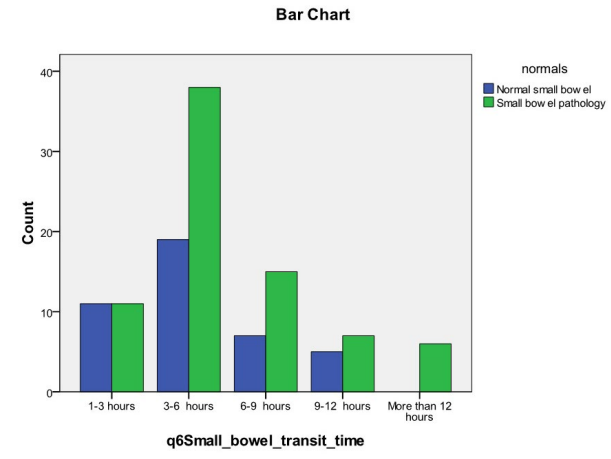

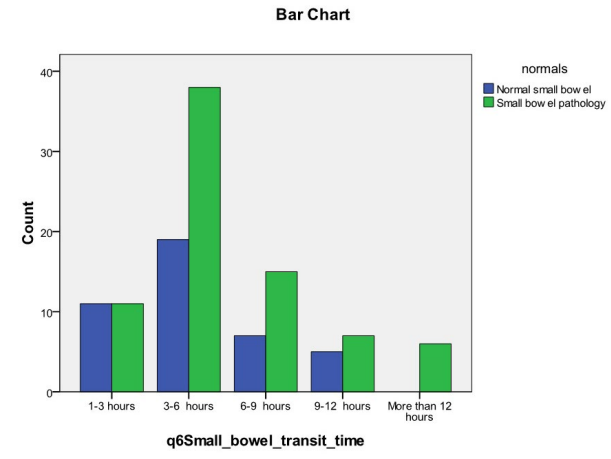

Gastric and small bowel transit time are defined as time interval between the first the last pictures taken in corresponding gastrointestinal tract. The mean small bowel transit time was 5 h 18 min. The duration of the small bowel transit time did not affect the diagnostic yield of the capsule endoscopy. The latter was affected by the underlying indication. The diagnostic yield for small bowel diarrhea, OGIB, and chronic abdominal pain were 80%, 63% and 50% respectively (Table 2) (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Cross tabulation: Small bowel transit time and diagnosis.

| Table 2: Small bowel transit time and normal and small bowel pathology cross tabulation. |

| Small bowel transit time |

|

Diagnosis |

Total |

| Normal small bowel |

Small bowel pathology |

| 1-3 hours |

Count |

11 |

11 |

22 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

50.0% |

50.0% |

100.0% |

| 3-6 hours |

Count |

19 |

38 |

57 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

33.3% |

66.7% |

100.0% |

| 6-9 hours |

Count |

7 |

15 |

22 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

31.8% |

68.2% |

100.0% |

| 9-12 hours |

Count |

5 |

7 |

12 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

41.7% |

58.3% |

100.0% |

| More than 12 hours |

Count |

0 |

6 |

6 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Total |

Count |

42 |

77 |

119 |

|

% within

Small bowel transit time |

35.3% |

64.7% |

100.0% |

Complications occurred in 5.8% of the patients undergoing capsule endoscopy and capsule retention was the main complication. Retention is defined as a capsule remaining in the gastrointestinal for longer than two weeks.

In 10% of patients the capsule examination was not complete as the capsule did not reach the ileocecal valve. The gastric transit time was not associated with complete examination rate. The gastric transit time ranged from 4 minutes to 9 hours. In 5/7 patients (71.4%) the gastric transit time was less than 90 minutes and in the remaining 2 patients it was more than 90 minutes (Table 3).

| Table 3: Gastric transit time in patients in which the capsule did not reach the iliocecal valve. |

| Number |

Gastric transit time |

Capsule retention |

| 1 |

46 min |

Yes |

| 2 |

16 min |

Yes |

| 3 |

14 min |

Yes |

| 4 |

1 hour |

No |

| 5 |

4 hours 47 min |

No |

| 6 |

8 hours 12 min |

No |

| 7 |

21 min |

No |

| 8 |

41 min |

Yes |

| 9 |

1 hour 16 min |

No |

| 10 |

9 hours |

No |

| 11 |

4 min |

No |

| 12 |

9 hours |

Yes |

DISCUSSION

CE has a good diagnostic yield in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding which has been reported from 38% up to 93 %.12 The first clinical trial by Lewis and Swain in 2001 compared capsule endoscopy to push enteroscopy in patients with OGIB. In which twenty patients with OGIB received both capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy. A site of bleeding was found in 55% of patients using capsule endoscopy compared to 30% for push enterscopy (p=NS).13 In our study, CE demonstrated the cause of bleeding in 39 of the 61 patients (63.9%) with obscure GI bleeding. Compared to 73.9% from a study done by Eroy O, et al. in which angiodysplasia comprises 53%, malignancy 6.3% and inflammatory disease 6.3% of the total number of patients presenting with OGIB.4

In our study the tumors were 7.6% cases,9 In a study by Gena M, et al. of 562 patients, 50 patients (8.9%) were diagnosed with small bowel tumors. The types of tumor diagnosed by capsule endoscopy included 8 adenocarcinomas (1.4%), 10 carcinoids (1.8%), 4 gastrointestinal stromal tumors (0.7%), 5 lymphomas (0.9%), 3 inflammatory polyps, 1 lymphangioma, 1 lymphangioectasia,1 hemangioma, 1 hamartoma, and 1 tubular adenoma. Of the tumors diagnosed, 48% were malignant and the pathology results were not available for 10 patients.14 It was also observed by Gena M, et al. that 9 of 67 patients (13%) younger than age 50 years who underwent capsule endoscopy for obscure bleeding had small bowel tumors. In our study 8 of the 9 patient diagnosed with small bowel tumors were above 55 years of age with the exception of 35 years old non responder celiac disease who was diagnosed as gastric lymphoma.

In our study Capsule endoscopy was indicated in 21 patients presenting with small bowel diarrhea, one of those patient suspected to have tuberculosis and treated accordingly. A study done by Dinesh K. Bhargava conclude that even though target biopsy is an effective method of diagnosis, anti-tuberculous chemotherapy may be started on the basis of the endoscopic appearance if there is a high clinical suspicion of tuberculosis,15 5 of those patients with small bowel diarrhea diagnosed with suspicion of Crohn’s disease, a recent meta analysis of 11 prospective comparative studies compared CE with other modalities found that CE had a better incremental yield, ranging between 15-44% compared with other modalities for both known and suspected Crohn’s disease and the ability to detect small bowel mucosal breaks in early Crohn’s disease. Fire man, et al. prospectively evaluated 17 patients with suspected Crohn’s Disease. Capsule endoscopy found evidence of Crohn’s disease (erosion, ulcers and strictures) in 12/17 patients (71%).16 In our study four patients underwent CE to detect small bowel involvement as part of evaluation for IBD. Evidence of small bowel lesions was seen in two patients. One of which was suspected as Crohn’s Disease on colonscopy, but the histopathology was not conclusive. CE revealed small bowel involvement and confirmed the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. In addition, ten other patients were diagnosed as Crohn’s disease, four presented with OGIB; five with small bowel diarrhea and another patient was suspected as Crohn’s Disease during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in which the CE revealed proximal jejunal stricture and underlying Crohn’s disease.

A young patient presenting with abdominal pain and a high eosinophil count was diagnosed as eosinophilic gastroenteritis based on a duodenal biopsy. CE revealed erythematous friable lesions with ulcerations, together with short villi in the proximal jejunum. These CE changes are non-specific and the definitive diagnosis involves histological evidence of eosinophilic infiltration in biopsy slides. The presence of more than 20 eosinophils per power field on microscopy is needed for diagnosis. As infiltration is often patchy, it can be missed and laparoscopic full thickness biopsy may be required.17,18

The MiRo CE used in this study is the smallest CE to date and offers both increased operation time with power saving technology and good image quality. The operation time of MiRo CE is almost 12 hours. A study done by Jeong Youp, et al. demonstrated that the longer the operation time increase the complete examination rate to 90%. A similar percent was obtained from our study (89.9%). Which also showed that the diagnostic yield was not improved by increased small bowel transit time; the p value was 0.1, which was found to be insignificant. A similar observation by Liao, et al. that reducing the capture rate in the stomach increase the complete examination rate, but not the diagnostic yield.19 In contrast to Jonathan, et al. study which demonstrated that prolonged small bowel transit time during CE is associated with an increased diagnostic yield, probably due to a positive effect on image quality during a “slower” study.20

Unlike operation time, diagnostic yield could also be affected by the subjective decision of to whom CE should be utilized. The diagnostic yield of CE would be high with strong suspicion of small bowel disease and low if suspicion is minimal.21 In Our study, the diagnostic yield was 63.9% when the indication was obscure bleeding compared to 70% obtained from Jeong Youp, et al. study. The highest yield was 80% with small bowel diarrhea and the lowest yield was in the three patients presenting with sub-acute intestinal obstruction, in which CE didn’t reveal any abnormalities.22

The use of capsule endoscopy for abdominal pain alone is less clear. Multiple studies have found contradictory results. Several abstracts have found the diagnostic yields to be low as four to 11%, while others found the yield to be as high as 54%. This difference is likely due to the heterogeneity of this study population.23,24,25 In our study, the diagnostic yield for abdominal pain was found to be 50%.

Delayed gastric emptying defined as gastric transit time more than 90 minutes, was suggested by some reports of being a significant factor for incomplete examination examination.26,27 In the past, a gastric transit time longer than 90 minutes meant that about 20% of the capsule’s time was wasted in the stomach, leaving less than 5 hours for small bowel examination. In contrast, the MiRo CE still had 10 more hours to operate after a gastric transit time of 90 minutes.22 In this study, the gastric transit time ranged from 4 minutes to 9 hours. In 5/7 patients (71.4%) the gastric transit time was less than 90 minutes and in the other 2(28.5) patients it was more than 90 minutes. However, even with the MiRo CE, an extremely prolonged gastric transit time still caused incomplete examination. In one case the capsule went into the small bowel after 2 hours for a short time and went back to the stomach and remained for another 7 hours. In another patient, the gastric transit time was also 9 hours leaving almost 3 hours for small bowel examination.

In our study, the CE was repeated in 5 patients, two were due to ongoing OGIB and negative results on CE. In patients with a negative CE and persistent OGB, a second look capsule endoscopy may be considered. If this is negative they should be referred for DBE. (recommendation (grade C)).

The second trial revealed underlying small bowel pathology in 4 of the 5 patients. Jones BH, et al. studied the yield of repeating wireless CE in patients with OGIB. And in ten patients with persistent gastrointestinal bleeding and previously negative capsule examination, a repeated study revealed additional findings in 50%.19

CONCLUSION

Capsule endoscopy is a very useful diagnostic tool, especially in the presence of a strong suspicion of small bowel pathology. The main indication for capsular endoscopy was OGIB, and angiodysplasia was found to be the main underlying cause.

Complication occurred in 5.8 % of the patients undergoing capsular endoscopy and capsular retention was the major complication. In 10% of patients the capsular examination was not complete and the capsule did not reach the ileocecal valve. The gastric transit time was not associated with complete examination rate. The duration of small bowel transit time during capsular endoscopy does not affect its diagnostic yield. The latter is affected by the underlying indication. The diagnostic yield for small bowel diarrhea, OGIB and chronic abdominal pain were 80%, 63% and 50% respectively. Repeating CE in patients with a previously negative capsule examination and a high suspicion of small bowel pathology may reveal addition finding in the majority of patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None of the authors have conflicts of interest.

CONSENT

The authors have obtained written consent from all the patients which includes information and agreement that this data will be published.