INTRODUCTION

The client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ-8)1 has been used in many settings, including healthcare to obtain feedback on services. Its use in the current study is timely as Qatar is witnessing an exponential growth in population and infrastructure projects. This is characterized by a large influx of expatriate workers to fill the many job opportunities in the construction, service, and healthcare sectors. Faced with the challenge to meet the healthcare needs of a growing population, Qatar’s healthcare system is undergoing tremendous transformation and modernization in terms of buildings, equipment, medical procedures, staff recruitment, training and professional development.2 This transformation, led by the Ministry of Public Health aims to provide high quality healthcare, including wound care of international standards. This is in accordance with Qatar’s National Vision 2030, the framework of Qatar’s future development.

Providing such high quality wound care requires that healthcare workers work effectively with their colleagues across other disciplines. This is often referred to as Interprofessional collaboration (IPC). There is evidence to support that employing a multidisciplinary team strategy in healthcare can lead to improved outcomes for patients.3,4,5,6,7 One study that examined the outcomes of IPC8 found that interprofessional team work decreases medical errors, improves patient satisfaction and patient care, and improves the knowledge and skills of professionals. In another study, the authors9 argue that the growing prevalence of non-healing acute and chronic wounds is a major concern. Additionally, the lack of united services aimed at addressing the complex needs of individuals with wounds is a major challenge. According to these authors, IPC in education and practice is very important in being able to provide the best patient care, enhance clinical and health-related outcomes and strengthen the healthcare system. These authors9 show that a review and analysis of 18 years of literature related to managing wounds as a team showed increasing evidence to support a collaborative team approach in wound care.

Another study,10 illustrated the importance of IPC in the treatment of wounds. The authors found that IPC can potentially reduce prevalence of wounds and improve wound care more efficiently. Therefore, IPC between healthcare providers should be encouraged as it facilitates appropriate assessment, diagnostic investigations, treatments and care for the patients with wounds.

Some authors11 infer that wound healing can be a complex process, and as such, patients with chronic ulcers require a systematic team approach from healthcare professionals. These authors argue that the wound care team members may vary based on the individual patient’s requirements. The interdisciplinary team therefore has to work both with the patients and their families to address the complex treatment requirements of patients with chronic wounds. Through this approach the healthcare professionals can positively influence healing of the chronic wounds by promoting, collaborating and participating in interdisciplinary care teams.

According to some researchers,12 IPC is very important for preventing pressure ulcers. As such, collaboration with interprofessional teams has been identified as one of the most commonly reported facilitators in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for wound care. Therefore, IPC as an approach to wound care is necessary for translating research into practice. These authors further explain that in order to prevent pressure ulcers, healthcare providers need consistent, vigilant, and interprofessional approaches. Accordingly, interprofessional workgroups, evidence-based approaches and system-level support will result in a decreased number of pressure ulcers in patients overall.

Researchers13 have found that a multidisciplinary structure of the healthcare team is one of the most important components of wound care. This approach would enable healthcare professionals to provide patient care, and work with others to achieve the best possible patient care. These authors also suggest that a multidisciplinary team approach has become an essential component of evidence-based management for both inpatient and outpatient cases of chronic wounds. Such a multidisciplinary team approach aims to combine the important disciplines that contribute to wound healing and to provide a holistic service to patients with multiple needs. This is accomplished through applying the best available evidence-based care. According to these authors, a multidisciplinary team approach results in improved wound healing and reduced amputation rates, reduced length of hospital stay, reduced number of home visits and a reduction in the incidence of pressure ulcers, thereby reducing the overall cost of care.

Gottrup3 argues that the idea of multidisciplinary teams has become very important in providing wound care. Multidisciplinary wound care collaborations have resulted in a reduction of required home visits, and the range of products used in treating wounds. This author also stresses the importance of the team approach and collaboration between all healthcare professionals to facilitate high quality holistic care for patients.

According to some researchers,9 adopting an interprofessional approach in wound management seems logical. However, the literature has failed to clarify terms such as multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary. As a result of lack of consensus on terminology, healthcare providers are confused as to what this approach to wound care means.

Patient satisfaction is a key indicator for healthcare quality, and for many years, a measure of health outcomes. The main aim of measuring consumer perception of quality of healthcare services is to utilize these measures to enhance and improve the delivery of care and in the last 40 years, the many instruments used to measure patient satisfaction have evolved.14 According to others15(p.972) “patient satisfaction is an individual’s perception and evaluation of the care they receive in a healthcare setting”. According to the authors, it is very important to understand patient satisfaction because of its association with retention to care and medication adherence, which in turn impact the health and quality of life (QoL) of the patients. Patient satisfaction is an important component of patient-centered care, aimed at improving health outcomes by reducing the gaps between patient perceptions and healthcare needs.16

This study assessed patient satisfaction in a hospital setting. The overall objective of this research study was to determine the level of patient satisfaction with wound care services provided through interprofesstional team approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Setting

To complete this research, a cross-sectional research design was chosen. Patients who received wound care services from an interprofessional team between January 2015 and March 2016 in the outpatient wound care clinic at Hamad General Hospital (HGH) in Doha, Qatar were asked to participate in the study. These patients were surveyed to determine their level of satisfaction with the wound care services received as they were delivered through an interprofessional team approach. HGH, located in Doha, Qatar, is a 600 bed inpatient adult tertiary hospital that receives and treats about 40,000 patients annually. Of this large number of patients seen, 30% are admitted. The rest are treated as outpatients and discharged. In 2014, a total of 165 patients came to the HGH outpatient clinic to receive wound care services. This number was confirmed through the outpatient clinic patient registry.

As the wound care service maintains a service user registry of all patients treated in the outpatient wound care clinic for planning purposes, this registry was the ideal place to obtain contact information for potential participants for the research study. After obtaining consent from ethical boards and prior to starting the research, a letter asking permission to conduct the study, accompanied by a summary of the study protocols, was sent to the executives in charge at the outpatient wound clinic. A meeting was then held with the executives to further explain the purpose of the study and to answer questions regarding the research.

Ethical Approvals

Prior to starting this research, ethical approval was first sought from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID: REB15-2811). A later amendment was obtained from the CHREB requesting that patient recruitment be done retrospectively through the wound care out-patient registry rather than asking patients to participate as they revive care at the clinic. Additional local ethical approval was equally sought and obtained from the Hamad Medical Corporation, Medical Research Center (Ref. No.: MRC/1457/2015).

Study Population

The study sample for this research was one of convenience. The convenience sample included all patients who have accessed wound care services from an interprofessional team approach at the Outpatient Wound Care Clinic at HGH between the time periods of January 2015 to March 2016. According to the patient registry at the Out Patient Wound Care Clinic, the complete patient sample of convenience could be as many as over 200 patients who have been treated at the clinic over this one year time period. The goal for sampling was to have as large a sample as possible for this data collection period.

Access to the patient registry to obtain contact information for the patients treated during the set time frame was coordinated through the head nurse for wound care at the Out Patient Clinic. Patients from the registry were called and asked if they would be willing to return to the wound care clinic to participate in a follow-up survey. Often the patients returned for treatment and the time of the survey was coordinated around the treatment times. When patients returned to the clinic, the researcher met with each patient to explain the purpose of the research and to invite the patient to participate in the study. An information letter about the study was provided at this time. The two ethical approval certificates were also available for presentation. Participants were invited to participate in the study and it was made clear that their participation was voluntary. They were also informed that they could drop out of the study at any time without penalty.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Patients were required to speak and understand English as the survey was conducted in the English language. Patients who were unwilling or unable to participate, who were under 18 years of age and who did not have the required English language skills were excluded from the study.

Survey Instrument

Patient satisfaction was assessed using a CSQ-8.1 Permission had been obtained from the developer to use the questionnaire for this study. The questionnaire had been used to measure satisfaction in numerous studies, some of which include: satisfaction with childbirth-related care among Filipino women17 satisfaction with hospital psychiatry services18 client satisfaction with psychotherapy,19 caregiver satisfaction with support services.20 The CSQ-8 has a known reliability factor as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, ranging from 0.83-0.931,21 and a validity factor of 0.8 on average; a significant correlation with other instruments measuring satisfaction.22 Additional questions were added to gather background information about patients including causes of wound, referral sources and socio-demographic characteristics.

Data Collection

Data collection was completed over a period of 3 months from December 2015 to March 2016. The CSQ-8 was administered through face-to-face interviews with each participant who agreed to participate in the study. The questionnaire was completed under the direction of the researcher in a private room at the Wound Outpatient Clinic at HGH. Eligible participants were scheduled for a set time to come and complete the survey during clinic hours. If the participants were scheduled to receive wound care services, the time to complete the questionnaire was coordinated with this time. Three wound care nurses and a head nurse assisted in scheduling the participants. The researcher conducted the survey as she ensured the standard process of the actual gathering of factual information was consistent.

Patients who received wound care treatments were asked to voluntarily participate in the study. After obtaining a signed consent participants were provided with clear instructions on how to complete the CSQ-8 questionnaire. The researcher was available to assist the participants who needed interpretation of the questions or who had questions about the questionnaire.

It became very obvious at the beginning of data collection that only soliciting patients who came to the clinic for wound care services would not provide a sufficient sample group. It was observed that there was a very small number of current patients and the target population would not be achieved. The decision was made to complete the data collection retrospectively from patients who had already received healthcare services at the clinic. As such, the researcher sought approval from the ethics boards to modify the data collection protocol. Once approved, patient contact information was traced from the clinic registry retrospectively.

Overall, 49.3% of study population were deemed ineligible to participate in the study and were then excluded. An additional 14.6% of eligible individuals were unable to come to the clinic to complete the questionnaire and as such, they did not participate in the study. At the completion of data collection 36.1% of the target population (N=219) participated in study. The total study population, those participants who completed the questionnaire was n=111.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was preceded by cleaning and verification of collected data to ensure a valid dataset for conducting analysis. Next, labels were assigned to response options for each CSQ-8 question. For example, question No. 1 on the CSQ-8 asks participants, “How would you rate the quality of service you received?” Response categories included 4-Excellent, 3-Good, 2-Fair, and 1-poor. The labels were assigned to each response option to facilitate interpretation of output from analysis. This process was repeated for all question items, making sure that the rank order was maintained. For example, question No. 8 on the CSQ-8 has four categories of responses including 1-No, definitely not; 2-No, I don’t think so; 3-Yes, I think so; 4-Yes, definitely. Though different in label and ordering sequence, the rank order is same for all questions on the CSQ-8 such that response option 1 is “less favorable” and response option 4 is “most favorable”. Previous studies have used varying methods to categorize CSQ-8 data using various cut off points for differing levels of satisfaction.23 As the authors could find no such consistency in methods of presenting data they used percentages to present CSQ-8 scores by the 4 levels of satisfaction.

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 20). Data analyses involved descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation and frequencies) for all eight question items assessing satisfaction with wound care services, as well as to describe study sample by socio-demographic characteristics. Subsequently, t-tests were used to compare mean satisfaction scores for study variables. For each CSQ-8 item, mean differences between subgroups were deemed significant at the 0.05 level of significance. The findings were summarized and presented in Tables and Figures.

RESULTS

In total 81 of the 111 eligible participants responded to the survey, giving a response rate of 73.0%. The average age of respondents was 44.5 years. A majority of respondents were male (65.4%), born outside of Qatar (75.3%), married (70.4%), had a college or university degree (40.7%) and were employed (61.7%) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants, Wound Care Service Users, HGH, Qatar, 2016 |

| Variables |

Frequency (%) |

| Age (years)

Mean (SD)

Range |

44.5 (15.6)

19-83

|

| Gender

Male |

53 (65.4) |

| Place of birth

Qatar

Outside Qatar |

20 (24.7)

61 (75.3)

|

| Marital status

Single

Married

Divorced

Widowed |

19 (23.5)

57 (70.4)

3 (3.7)

2 (2.5)

|

| Level of education

Primary or less

Secondary school

High school

College/university |

13 (16.0)

12 (14.8)

23 (28.4)

33 (40.7)

|

| Employment status

Employed

Unemployed

Retired

No response |

50 (61.7)

17 (21.0)

12 (14.8)

2 (2.5)

|

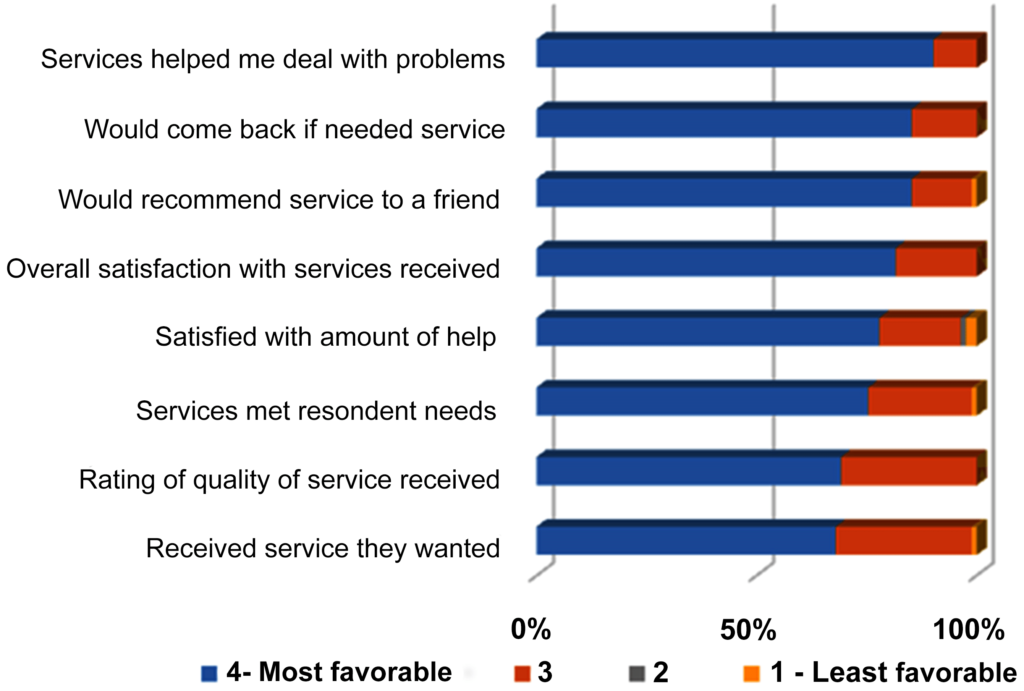

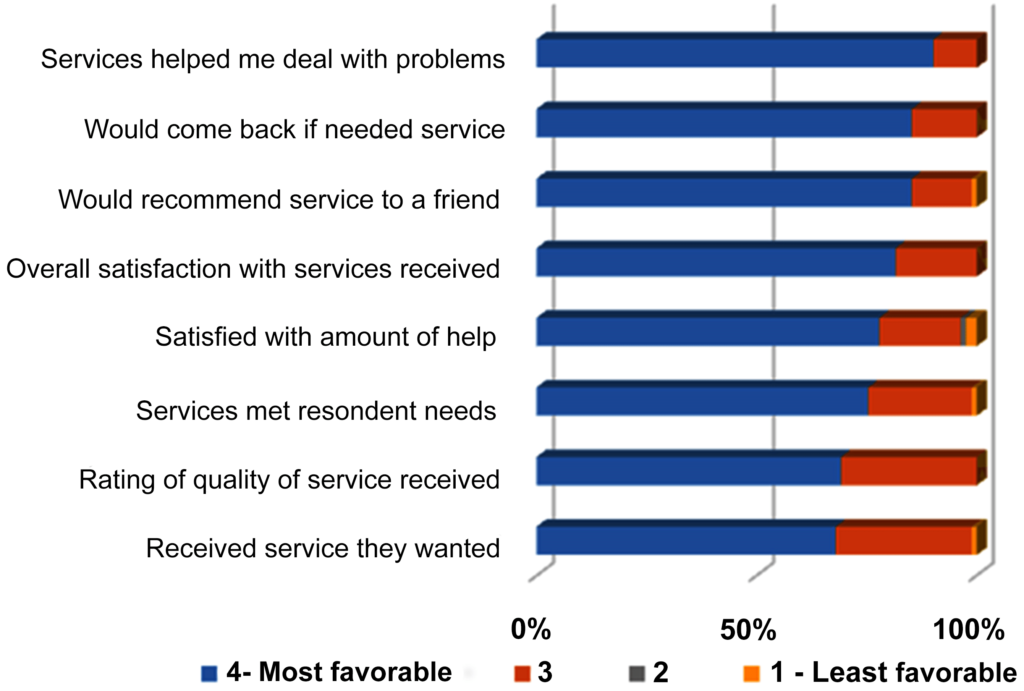

The results presented various levels of patient satisfaction with wound care services at HGH. In summary, all respondents (100%) rated the quality of service they received as “excellent” or “good” and a majority of respondents (98.8%) reported receiving the kinds of service they wanted. A majority (98.8%) of respondents indicated that the services provided met “most” or “almost all” of their needs. Most of the respondents (98.8%) would recommend the services provided by the wound care unit to a friend that needed help and 96.3% indicated that they were “very satisfied” or “mostly satisfied” with the amount of help they received. All respondents (100%) reported that the services they received helped them “a great deal” or “somewhat” in dealing with their problems. As to overall satisfaction, 100% of respondents reported “very satisfied” or “mostly satisfied” with the services they received overall, general sense. Finally all respondents (100%) reported that they would return to the wound care service if they needed help again. Figure 1 is a detailed summary of all the responses to the CSQ-8 questionnaire, ranked from most favorable (4 highest rank) to least favorable (1 lowest rank) response, for each question.

As shown in Figure 1, there are variations in favorability ratings (percentage of responses attributed to rank 4 on the CSQ-8). The most favorable area of client satisfaction on the CSQ-8 was, “Have the services you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems” with 90.1% of respondents reporting that, “Yes, they helped a great deal”. In contrast, the least favorable area of the CSQ-8 was, “Did you get the service you wanted?” with 67.9% of respondents indicating, “yes, definitely”.

Figure 1: Summary of Measures of Client Satisfaction with Wound Care Services

A comparative analysis of patient satisfaction scores by subgroups did not portray relevant information worth reporting. However, Table 2 illustrates mean satisfactions scores for CSQ-8 by sex. No statistically significant differences between male and female in terms of reported satisfaction with wound care services at HGH. Nevertheless, a noticeable pattern emerged. Compared to women, men reported higher levels of satisfaction for CSQ Q1, Q2, and Q3; and lower levels for CSQ Q4 to Q8.

| Table 2: Comparison of CSQ-8 Satisfaction Scores by Sex, Wound Care Service Users, HGH Qatar, 2016. |

| CSQ-8 |

Sex |

N |

Mean |

Std.

dev |

Mean

Diff. |

t-test for equality of means |

| t |

df |

p-value |

| Q1 |

Male |

53 |

3.68 |

0.471 |

-0.024 |

-0 .220 |

78 |

0.826 |

| Female |

27 |

3.70 |

0.465 |

| Q2 |

Male |

53 |

3.62 |

0.596 |

-0.081 |

-0.617 |

78 |

0.539 |

| Female |

27 |

3.70 |

0.465 |

| Q3 |

Male |

53 |

3.64 |

0.591 |

-0.247 |

-2.023 |

78 |

0.046 |

| Female |

27 |

3.89 |

0.320 |

| Q4 |

Male |

53 |

3.85 |

0.496 |

0.071 |

0.637 |

78 |

0.526 |

| Female |

27 |

3.78 |

0.424 |

| Q5 |

Male |

53 |

3.72 |

0.601 |

0.013 |

0.090 |

78 |

0.929 |

| Female |

27 |

3.70 |

0.669 |

| Q6 |

Male |

53 |

3.91 |

0.295 |

0.017 |

0.234 |

78 |

0.816 |

| Female |

27 |

3.89 |

0.320 |

| Q7 |

Male |

53 |

3.85 |

0.361 |

0.108 |

1.169 |

78 |

0.246 |

| Female |

27 |

3.74 |

0.447 |

| Q8 |

Male |

53 |

3.87 |

0.342 |

0.053 |

0.623 |

78 |

0.535 |

| Female |

27 |

3.81 |

0.396 |

DISCUSSION

This study examined patient satisfaction with wound care services in Qatar. The overall objective was to determine the level of patient satisfaction with an interprofesstional approach to wound care service at the Outpatient Wound Care Clinic at the HGH.

Overall, findings from this study were very positive, with often high ratings of patient satisfaction. Though high, variations in favorability ratings emerged, suggesting there are still areas that need improvement, therefore cannot be ignored. The observed findings are comparable with other studies,3,4,5,6,7,8 that found that employing a multidisciplinary team strategy in healthcare delivery can lead to improved outcomes for patients. Subgroup analyses of satisfaction levels revealed no differences worth reporting. This is a welcomed finding for a healthcare system that seeks to reduce inequities in healthcare services utilization, an important surrogate indicator for health system performance.

This study had a few limitations. It involved a convenience sample drawn from one of several hospital sites providing wound care services in Qatar. Thus, the findings have to be interpreted with caution as they may not totally reflect the situation at all sites providing wound care services. Second, the study used a cross sectional design where participants had to recall their experiences receiving care. This may subject some participant responses to recall bias.Third, the CSQ-8 used in this study was administered in English; and in some cases, the questions were read out to participants and their responses crossed out on the questionnaire. Though not all respondents needed help completing the questionnaire, socially desired responses might have been collected from others who received help.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first of its kind in Qatar to examine patient satisfaction with an interprofessional approach to wound care services in Qatar. The researcher encountered some difficulties with recruitment but did overcome them to complete data collection. Overall, results show that patients were mostly satisfied with wound care services and this can be improved. The strength of this proposed study is that study results could have major implications for Qatar, especially as there are known efforts to introduce interprofessional practice to other areas in Qatar. To date there is limited published literature on the advantages of interprofessional practice for patients living in Qatar and the Middle East.

The Qatar SHC has openly expressed support for innovations capable of helping to achieve its prescribed goal – to provide high quality healthcare of international standards in accordance with Qatar’s National Vision 2030. Thus, this proposed study is timely, and its implications could be far reaching as the results will inform the design, implementation and adoption of interprofessional practice in healthcare delivery as a way to improve patient care in Qatar. Building on the evidence from this study, more research can be generated to fill the knowledge gap on the subject especially in the Middle Eastern countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is drawn from a Master of Nursing theses, University of Calgary by Ms. Shaikha Ali Al Qahtani. An electronic theses with the same title is uploaded on the website of the University of Calgary under the link: http://theses.ucalgary.ca/handle/11023/3431

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.