INTRODUCTION

Neutering is seen as the primary method for population control and is also routinely conducted by animal shelters to avoid further multiplication of homeless dogs.1,2 There are always controversial discussions about neutering dogs, since such an intervention implicates both advantages and disadvantages. Beside several health effects such as an increased risk for cancer, many behavioural changes such as excessive barking and increased anxiety can occur, as shown in a study of castrated Vizslas.3 Thereby the age at the time of neutering, the breed itself and the sex of the animal are taken into consideration. Accordingly, these effects should be weighed against each other before the decision for or against a castration is taken.4

Neutering, gonadectomy or castration refers to the surgical removal of the reproductive organs, and consequently to a great decrease in the production of gonadal steroids.5 Even though it is frequently recommended and performed however, the full extent of its consequences for the animal remains unclear. Over the last few years, some attention has therefore been given to the long-term health effects of neutering dogs. One repeatedly investigated issue is the influence of neutering on various types of cancer. On the one hand, there is a well-established opinion that the castration of bitches reduces their risk of developing mammary tumours. However, a recent review of this topic by Beauvais et al6 states that currently, the evidence presented in the reviewed papers is insufficient to show a reductive effect of neutering on mammary tumours. On the other hand, an increased risk of various cancers has been shown in several studies. Teske et al7 found that castration favours the progression of prostate carcinoma in dogs, and Zink et al3 state that gonadectomised Vizlas have a higher probability of developing hemangiosarcoma, mast cell tumours, lymphosarcoma and lymphoma as well as other kinds of cancer. A study on Golden retrievers2 as well as one reviewing the cause of death for over 40,000 neutered and intact dogs8 present similar results, stating that neutered dogs have an increased risk for several types of cancer. Apart from cancer, neutering has also been shown to correlate with an increased rate of autoimmune diseases and other diseases such as joint disorders (hip dysplasia and cranial cruciate ligament tear;2,9 and dermatological conditions such as a change in coat or fur quality).10

Adult male dogs are often castrated with the aim to remove undesirable behaviour such as mounting, roaming, aggressiveness and urine marking. However, the degree to which a behavioural pattern is changed via castration is not clearly defined.11 On no account, can neutering replace a proper education and appropriate socialization of the dog. Nor should it be considered as a panacea against all undesirable behaviours, although it may have positive effects on the dog’s behaviour in certain cases.12 The effects of a castration are dependent on the dog’s personality and they do not affect every behavioural pattern, since not all behaviours depend on sex hormones.

The experiences of the dog before neutering should not be disregarded. A dog can occasionally recall its possible positive sexual activities and will continue to show these behaviours, even though they might not be hormonally dependent.5 Nevertheless, all animals should be considered individually with the supposition that the population control should play a subordinate role in relation to the health of the animals.13

Less well understood and perhaps more difficult to investigate are the effects of neutering on the behaviour of dogs. Research in this field has resulted in a better understanding of certain aspects of behavioural alterations in neutered dogs. For one, several studies show neutered dogs to be more excitable and anxious than their intact conspecifics: A review of medical records and online surveys found that neutered dogs are more likely to have separation anxiety and fear of storms than intact animals.3,14 Additionally, an experimental study using 38 test subjects separated into three groups (gonadectomised at the age of seven weeks, seven months or left intact) judged all neutered dogs to be generally more active and males gonadectomised at seven weeks to be more excitable than intact individuals.15 Gonadectomy was also found to be correlated with a higher risk of developing other behavioural problems connected to fear and anxiety as well as hyperactivity.3 Concerning aggression, the public opinion of the effects of neutering seems to clash most severely with scientific evidence. There is a popular belief among dog owners that neutering result in less aggressive behaviour.16 However, a study on aggression in English cocker spaniels found that neutered and intact males did not differ in their likelihood of showing aggressive behaviour in any of 13 tested situations.17 Moreover, females neutered before showing any signs of aggression were more likely to behave aggressively towards children of the same household than intact females. Similar results of increased aggression in gonadectomised dogs were also found in more recent studies.3,18 In addition to various behavioural aspects, neutering may also influence dogs on a cognitive level. This seems especially noticeable at a high age, when intact males show less or less severe signs of cognitive impairments than neutered males.19 This is hypothesized to be an effect of the circulating testosterone, which may cause the progression of cognitive impairment to slow down. If and how the cognitive abilities of a dog are affected by neutering at a younger age is not yet known.4

Furthermore, there are studies in rodents, which indicate that estrogens improve memory and learning behaviour, for example by estradiol, which appears to interact with cholinergic systems. Both estrogens and testosterone reduce accumulation of the beta-amyloid, and testosterone, so it is suspected that it also prevents the phosphorylation of “neuroprotective protein tau”.19 To the surprise of some owners, their castrated dogs even show real sexual behaviour after years, which could also be due to the dopamine level, which can be stimulated by such behaviour.20 The persistence of “male” behaviour after neutering is not due to potential remainders of sex androgens in the blood, since the testosterone in the plasma decreases within six hours after castration onto a low to no longer measurable concentration.11 Furthermore, studies, in which animals were both castrated and adrenalectomised, excluded the possibility that the sexual behaviour of castrated animals is maintained by the adrenal androgens.11

It is a common theory that aggressive behaviour is generally related to testosterone and thus strives for ranking and competition for mating partners. However, for example, fear-related aggression is controlled by stress hormones such as cortisol and this in turn can be inhibited by testosterone. Thereby, a fear-enhancing effect and thus still unsafe behaviour can occur once the testosterone antagonist is no longer present after a castration.20

Some dog owners fear that owning a male dog directly amounts to undesirable behaviour and they are of the opinion to get around this by an early castration.21 But in early castrated males it should be noted first of all that the testosterone is responsible for the healthy development of the penis and thus the penis and the penis bone can remain infantile and the foreskin can remain small and underdeveloped.4

These results are also supported by Beach et al,22 who found that in males who have been castrated at birth, the penis never grew to the normal size. The closing of the growth plates of the bones is partly controlled by sex hormones. Animals that are neutered before this closing of the growth plates thereby experience prolonged bone growth. Furthermore, Zink et al3 investigated the risk of developing cancer in the dog breed Vizsla and they found out that there is an increased risk for this disease in early castrated dogs. In a study of aggressive behaviour the finding was, that prepubertally castrated males are as aggressive as intact ones.11 Also early castrated males seem likely to suffer more frequently from hip dysplasia (HD) than intact dogs, which could also be connected with the extended bone growth. Additionally, the risk of a cranial cruciate ligament rupture occurs twice as much in early castrated dogs.4

Little is known about the consequences of neutering on the social behaviour of dogs. In the first part of our study, the focus therefore lies on the social behaviour of male dogs among themselves. The question to be answered here is whether there are differences in certain behaviours between neutered and intact male dogs. There are several aspects of neutering that may found the assumption of behavioural differences. So the object of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of the effects of neutering on the behaviour of male dogs by way of video recorded trials and two different questionnaires. Therefore, three hypotheses are formulated as follows: (1) Certainly shown in a different frequency by neutered and intact male dogs. (2) Neutered males show confident behaviour less frequently than intact males. (3) Intact and neutered males differ in their frequency of sending and receiving social behavioural responses.

In the second part two different questionnaires about a dog’s behaviour and habits were distributed among owners of intact and neutered males.

In the second part, neutered and intact male dogs are being compared with respect to their trainability, boldness, calmness and dog sociability. Even though there is evidence for gonadectomy affecting a dog’s cognitive abilities, a study on trainability in dogs found no clear correlation between neuter status and trainability.19,23 Similarly, no difference in trainability of neutered and intact dogs is expected in this analysis. However, bearing in mind the findings of previous studies on excitability, fearfulness and aggression,3,14,15,17,18 intact males are expected to be bolder, calmer and more sociable than neutered ones.

Finally, a more general comparison of neutered and intact male dogs is being conducted looking at various habits and behaviours in everyday life, such as restlessness, stereotypies and aggression in different situations; as well as at problems and difficulties owner are having with their dogs. In accordance with the previously mentioned hypothesis, intact dogs are again expected to be calmer and less aggressive than neutered ones. Also bearing in mind the findings of previous studies,3,14 problems mentioned by owners of neutered males are predicted to include fearful behaviours, panic or hyperactivity more often than those mentioned by owners of intact dogs.

Overall, this study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the long-term effects of neutering on the behaviour of male dogs by analyzing the social behaviour of neutered and intact animals as well as by evaluating questionnaires submitted by dog owners.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Video Analyses

Data on social behaviour was collected on groups of dogs consisting in equal parts of neutered and intact males in Germany and Switzerland (some of the dogs already knew each other from the dog schools). The dogs were released together into an enclosure and their behaviour was recorded using focal-animal-sampling with a video camera. Each individual was video recorded for 5 minutes. The first order of the focal animals was chosen randomly. In subsequent meetings, the order was rotated in a way that allowed for every dog to be recorded once in every position. This trial was conducted with six separate groups of dogs (17 intact, 16 neutered). The composition of the dog groups and further information about the participant dogs are shown in Table 1. For all groups, the meetings took place on the terrain of dog schools. In both cases, the dog owners were also inside the enclosures, as well as the owners of the dog school and one or two camera operators.

| Table 1: Overview of the Participants of the Video Trials and their Classification to each Group. |

| Group No. |

Label |

Breed |

Age |

Neutering status |

| 1 |

I1 |

Airedale Terrier |

1 year |

intact |

| I2 |

German Shepherd |

8 months |

Intact |

| N1 |

German Shepherd |

5 years |

neutered |

| N2 |

Kangal mixed breed |

9 years |

neutered |

| 2 |

I3 |

Grand Anglo Francois Tricolor |

1 year |

intact |

| I4 |

Golden Retriever |

1 year |

intact |

| N3 |

Labrador Retriever |

3 years |

neutered |

| N4 |

Mixed breed |

2.5 years |

neutered |

| 3 |

I5* |

Barsoi |

5 years |

intact |

| I5° |

Belgian Shepherd |

1 year |

intact |

| I6 |

Giant Schnauzer |

3 years |

intact |

| I7* |

English Springer Spaniel |

1 year |

intact |

| I7° |

English Mastiff |

6 years |

intact |

| N5 |

Rhodesian Ridgeback |

5 years |

neutered |

| N6 |

Kerry Blue Terrier |

5 years |

neutered |

| N7 |

Australian Kelpie |

2 years |

neutered |

| 4 |

I8 |

Labrador |

4 years |

intact |

| I9 |

Chihuahua |

2 years |

intact |

| I10 |

Shepherd-mix |

4.5 years |

intact |

| I11 |

Boxer |

3.5 years |

intact |

| N8 |

Newfoundlander |

4 years |

neutered |

| N9 |

Schnauzer |

10 years |

neutered |

| N10 |

Dachshund |

4.5 years |

neutered |

| N11 |

Labrador-mastiff-mix |

20 months |

neutered |

| 5 |

I12 |

Labrador retriever – Swiss – Briard – Mix |

5 years |

intact |

| I13 |

Australian Shepherd |

6 years |

intact |

| I14 |

Field Trial Labrador Retriever |

3 years |

intact |

| I15 |

Papillon |

– |

intact |

| I16 |

Bulldog |

– |

intact |

| N12 |

Greater Swiss Mountain Dog |

4 years |

neutered |

| N13 |

Leonberger |

5 years |

neutered |

| N14 |

Labrador Retriever mix |

7 years |

neutered |

| N15 |

Golden Retriever |

– |

neutered |

| N16 |

Mix |

– |

neutered |

| ‘I’ is used for intact males and ‘N’ is used for neutered males. A star (*) is used to label the males participating only in the first meeting of group 1, and the same label with a circle (°) for their respective replacements. |

Questionnaires and Case Studies

The second phase of data collection consisted of the evaluation of a survey first established for a study in Budapest by Turcsán et al.24 This questionnaire comprises a total of 24 questions about a dog’s habits in various situations, which can be evaluated using a preset point system and therefore allows for providing individual scores on the four traits of trainability, boldness, calmness and dog sociability (Table 2). A total of 133 surveys completed by owners of male dogs were available for analysis, 29 of which were submitted by participants of the dog groups of the video analysis trials.

| Table 2: Classification of the 16 Questions of the Questionnaires (based on Turcsán et al24) into the Four Personality Traits (Here it must be Emphasized that in Turcsan et al24 “Boldness” is used as one of the 5 Feactors, Corresponding to the Factor Extraversion, not to the Supertrait “bold” of the Shy-Bold-Concept, e.g., in Behavioural Ecology. |

| Calmness |

Trainability |

Dog Sociability |

Boldness |

| My dog can be stressed easily |

My dog is very easy to warm up to a new toy |

My dog fights with conspecifics frequently |

My dog is unassertive, aloof when unfamiliar persons enter the home

|

| My dog is emotionally balanced and not easy to rile |

My dog is ingenious, inventive when seeks hidden food or toy |

My dog is enthusiastic and animates (encourages?) other dogs to play |

My dog is rather cool, reserved |

| My dog is cool-headed even in stressful situations |

My dog often does not understand what was expected from him/her during playing |

My dog is suspicious (mistrustful? leery?) of other dogs |

My dog is sometimes fearful, awkward |

| My dog is sometimes anxious and uncertain |

My dog is not much interested except in eating and sleeping |

My dog is often bullying with conspecifics |

|

|

My dog is intelligent, learns quickly |

|

|

The questionnaires evaluated in the third part of the study were taken from archived files of dog owners taking part in an animal behaviour consultancy program called Einzelfelle (www.Einzelfelle.de) by zoologist PD Dr. Udo Gansloßer and veterinarian Sophie Strodtbeck. In the course of this program, people seeking advice in the management of their pets were asked to give their reasons for seeking council and to fill in questionnaires consisting of questions about their dog’s environment, health, habits and obedience. The files of 54 participants (27 intact and 27 neutered males) were examined regarding the reasons for participation in the program. They included fully completed questionnaires which were evaluated as to various behaviour patterns in everyday situations (Table 3). None of the neutered dogs referred to consultancy were castrated for reasons of aggression, stress or similar specific “diagnosis”. Instead there were dogs castrated because it was thought customary to do so or for reasons such as keeping with an intact bitch, being prevented to enter dog- daycare facilities otherwise, routinely in animal shelters, etc.

| Table 3: List of Issues Mentioned as Reasons for Seeking Council in Dog Management as well as of Behaviour Patterns Examined in this Paper. The Information of both Reasons and Behaviour Patterns was Obtained from Questionnaires using yes-or-no Questions. The Owners were Asked to fill in these Parts by Ticking for “yes”. |

| Reasons for seeking council |

Behaviour patterns |

| Consideration of neutering |

Restlessness |

| Epilepsy |

Dog is never tired |

| Thyroid abnormalities |

Nervousness |

| Stress/insecurity |

Absent-mindedness |

| Panic |

Shaking |

| Hyperactivity |

Panting without heat |

| Aggression |

Excessive licking/scratching |

| Else |

Stereotypic behaviour |

| Barking/whining |

|

| House-training unsuccessful |

|

| Lead pulling |

|

| Excessive demand for attention |

|

| Aggression against dogs |

|

| Aggression against humans |

|

| Chasing |

|

Data Analyses

The analysis of the video recordings of social behaviour was conducted using an ethogram originally created by Goodmann et al25 and modified by Spitzley and Elsing as well as Feddersen-Petersen (for detailed description of included behaviours see Appendix, Ethogram).26 All included behaviours were recorded as either sent by or received by the focal individual. For behaviour patterns seen as events, the number of occurrences was counted. For state behaviours the total duration of the behaviour was recorded to the nearest second.

Statistical and graphical analyses of the behaviour recordings were performed using the statistical program SPSS.24 Significances of frequencies were calculated using a Mann-Whitney-U-test for two- tailed independent data and a Kruskal-Wallis-Test for dependent data. Additionally a one-way ANOVA (randomization test) of the behavioural states was conducted via the online statistical program “StatKey” (http://www.lock5stat.com/StatKey/). The p-values were calculated by an online calculator (http://www.socscistatistics.com/pvalues/fdistribution.aspx). However, not all 33 dogs, but only the recordings of 26 dogs could be analyzed in the ANOVA.

The results of the BUDAPEST surveys and the Einzelfelle questionnaires were evaluated descriptively and depicted as graphs using SPSS Version 24 as well as Microsoft Excel (2010).

RESULTS

Video Analyses

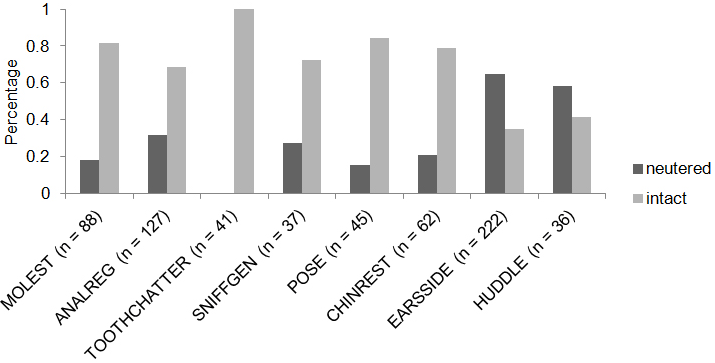

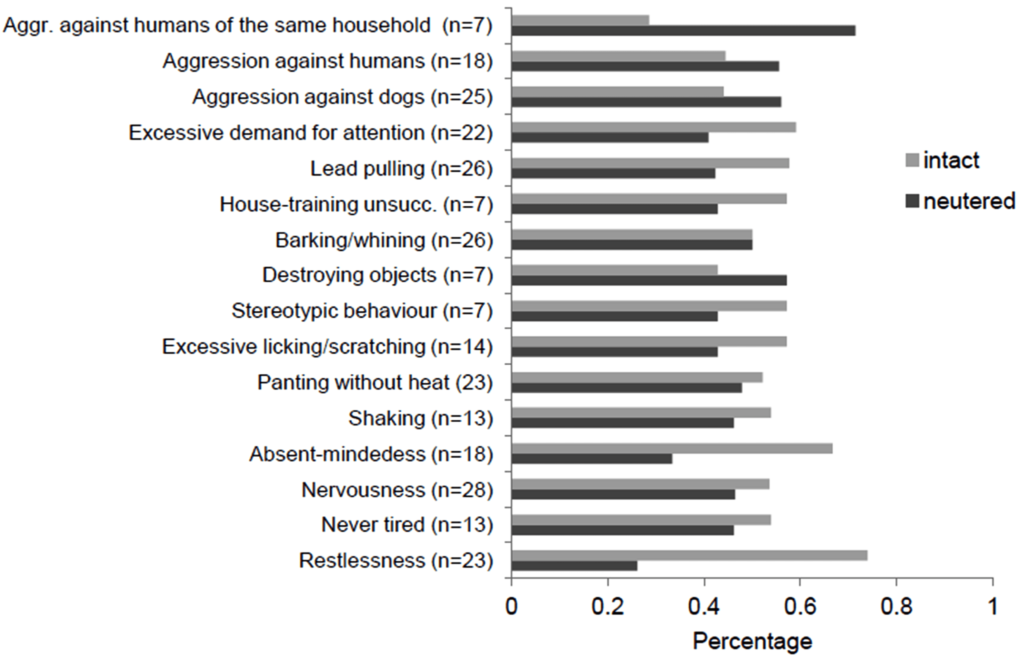

For the evaluation of social behaviour amongst neutered and intact male dogs, an ethogram consisting of 23 behavioural patterns was used. The analysis was conducted in two parts, the first of which was an evaluation of behaviour sent by focal dogs whereas the second part considered received behavioural patterns. There are significant differences among the behavioural patterns ‘molest’, ‘Sniffing of anal region’, ‘Sniff genitals’, ‘Pose’ and ‘Chinrest’ between the intact and castrated dogs. All these behaviours were recorded from more intact than neutered male dogs. Moreover the ’Toothchatter’ represents a behavioural pattern only shown by intact ones (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of the Frequencies of each Behavioural Pattern sent by Neutered and Intact Dogs (n=658)

ANALREG=Sniffing of Anal Region, SNIFFGEN=Sniff Genitals. The Statistical p-Values (Mann-Whitney-U-Test) are as Following: Molest: p=0.001; Analreg: p=0.005; Toothchatter: p=0.006; Sniffgen: p=0.020; Pose: p=0.015; Chinrest: p=0.061; Earsside: p=0.342; Huddle: p=0.488.

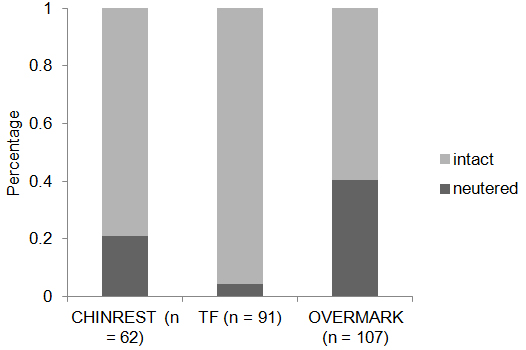

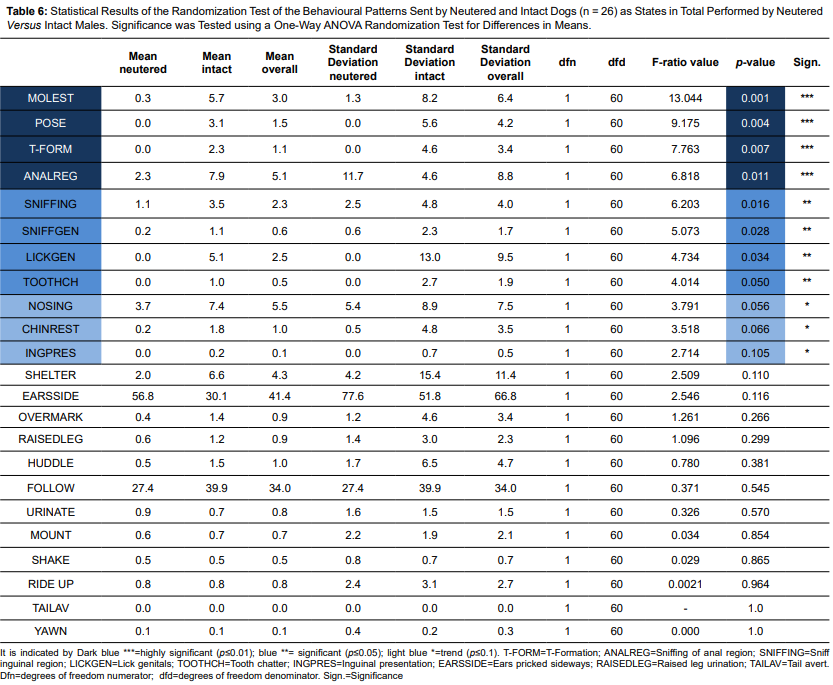

For the confident=assertive behaviours, which were a sample category of our ethogram, consisting of the following elements ‘chinrest’, ‘T-formation’ and ‘overmark’, the plotted data show that there are big differences for the behaviour of ‘chin rest’ between the neutered and intact male dogs. Equally the frequency of sending ‘T-Formation’ is higher by the intact dogs. The same applies to ‘Overmarking’, which also occurred more frequently in intact than castrated dogs (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of Frequencies of the Three Confident Behaviours ‘chin rest’, ‘

T-formation’(TF) and ‘Over Mark’ sent by Intact and Neutered Males (n=260)

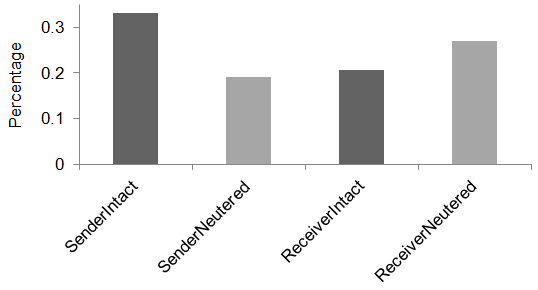

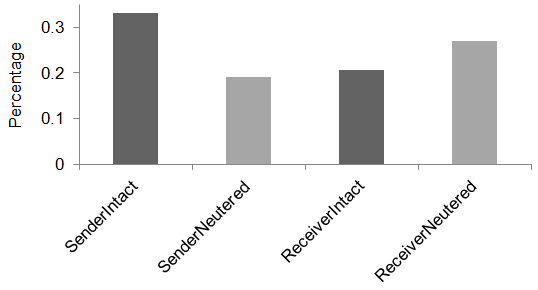

Figure 3 shows that the castrated males have a significantly lower proportion of sending social behaviour (19%) than the intact dogs (33%). Whereas in terms of receiving social behaviours, the percentage of the neutered dogs (27%) is higher than of the intact males (21%).

Figure 3: Percentage of the Frequency of all Behavioural Patterns Sent and Received by Neutered and Intact Dogs

(SenderIntact: n=905; Sender Neutered: n=525; Receiver Intact: n=562; Receiver Neutered: n=738; Total n=2730)

The stastical p-values (Mann-Whitney-U-Test) are as Following: Sender Intact/Sender Neutered: p˂0.0005;

Receiver Intact/ReceiverNeutered: p=0.280; Receiver Intact/Sender Intact: p=0.026; Receiver Neutered/Sender Neutered: p=0.184.

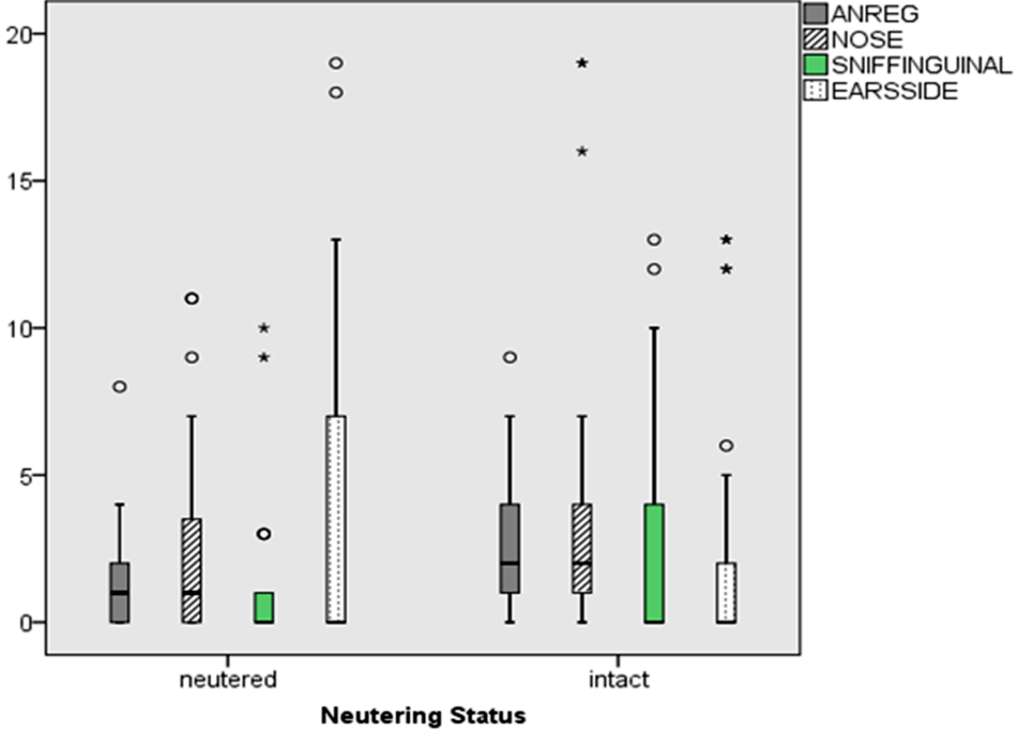

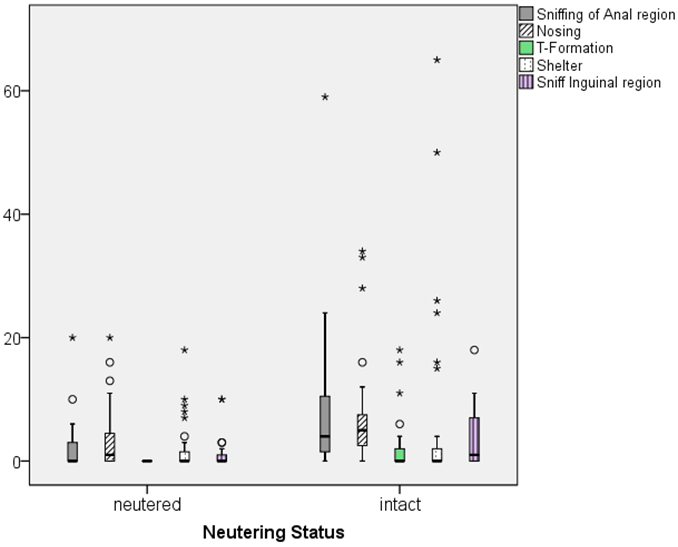

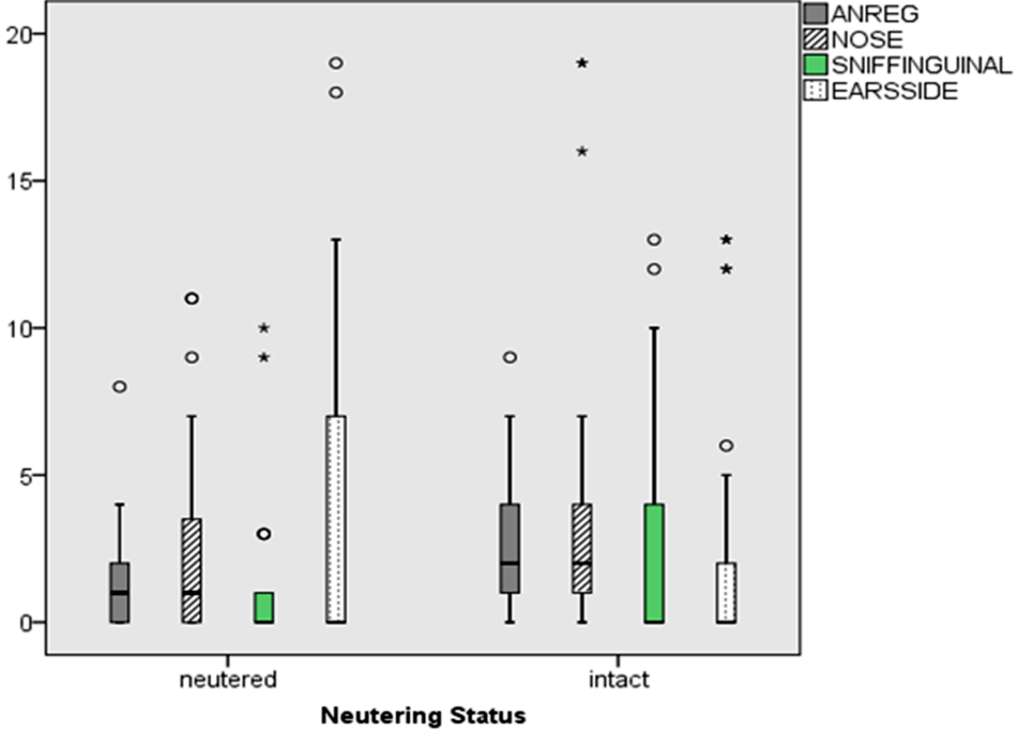

Certain behavioural patterns like ‘Sniffing of anal region’, ‘Nosing’ and ‘Sniffing the inguinal region’, are shown more frequently by intact than neutered males with the exception, that the median is the same for ‘Sniffing inguinal region’ (Figure 4). Keeping the ‘Ears pricked sideways’ can be recorded more for castrates, but here again there is no difference between the median values.

Figure 4: Comparison of the Frequencies of Each Behavioural Pattern Sent by Neutered and Intact Dogs (n=34 Dogs)

ANREG=Sniffing of Anal Region, NOSE=Nosing, SNIFFINGUINAL=Sniff Inguinal region, EARSSIDE=Ears pricked sideways. The

statistical p-values (Mann-Whitney-U-Test) are as following: Anreg: p=0.005; Nose: p=0.077; Sniffinguinal: p=0.158; Earsside: p=0.342.

Statistical Analyses

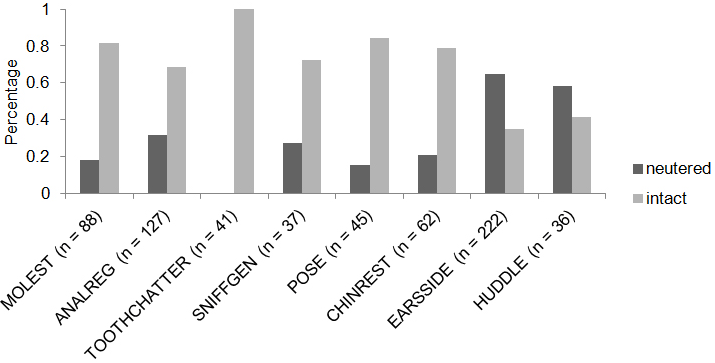

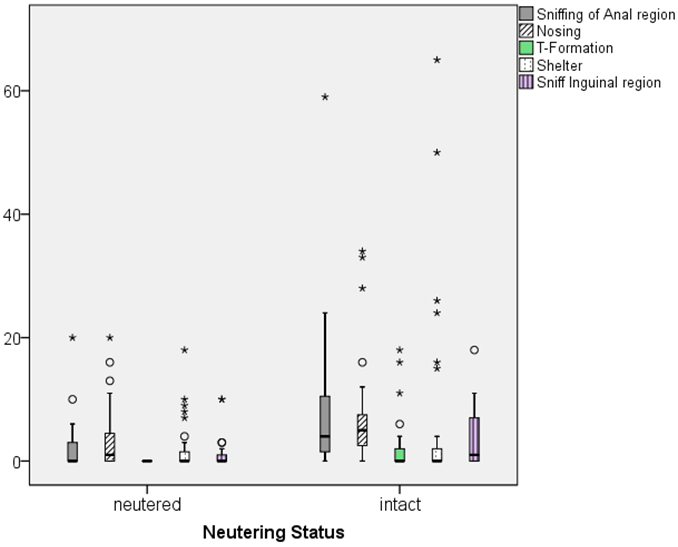

The statistical analysis of the social behaviours frequently sent by the neutered and intact dogs reveals significant differences between the castrates and the intact dogs (Figure 5) (see Appendix, Table 4). Highly significant results can be found in the behavioural patterns of ‘Molest’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=382.000, p=0.001), ‘Sniffing of anal region’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=568.000, p=0.005), ‘Licking genitals’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=475.000, p=0.008) and ‘Toothchattering’ (Mann- Whitney-U-Test, U=575.000, p=0.006). The behaviours ‘Sniffing genitals’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=464.000, p=0.020), ‘Pose’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=492.500, p=0.015) and ‘T-formation’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=475.500, p=0.018) differ significantly. At last the two behaviours ‘Nosing’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=465.000, p=0.077) and ‘Chinrest’ (Mann-Whitney-U-Test, U=492.500, p=0.061) reflect a trend among the castrated and non-castrated dogs. When looking at the statistical analysis of the behavioural patterns as ‘states’ (see Appendix, Table 5), significant differences or at least trends can be found for the same behaviours as those as shown in the analysis of the frequencies (see Appendix Table 6). But apart from these nine behavioural events (molest, sniffing the anal region, licking genitals, tootchchatter, sniff genitals, posing, T-Formation, chinrest and nosing), two other behavioural patterns are statistically relevant, if the video trials are analysed for their duration. These behaviours are ‘Sniffing the inguinal region’ (F=6.203; p=0.016) and ‘Inguinal presentation’ (F=2.714; p=0.105).

Figure 5: Comparison of the Duration of each Behavioural Pattern Sent by Neutered and Intact Dogs (n=34 dogs)

The Statistical p-Values (by an ANOVA Randomization Test) are as Following: Sniffing of Anal Region:

p=0.011; Nosing: p=0.056; T-Formation: p=0.007; Shelter: p=0.110; Sniff Inguinal Region: p=0.016.

Questionnaires

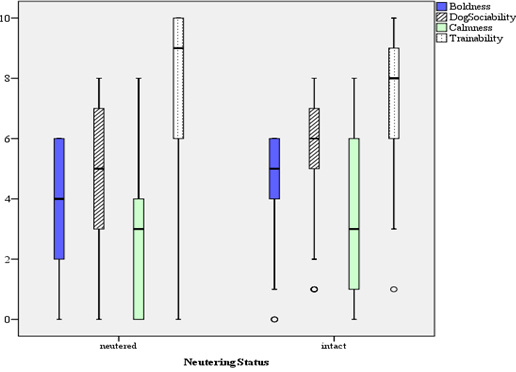

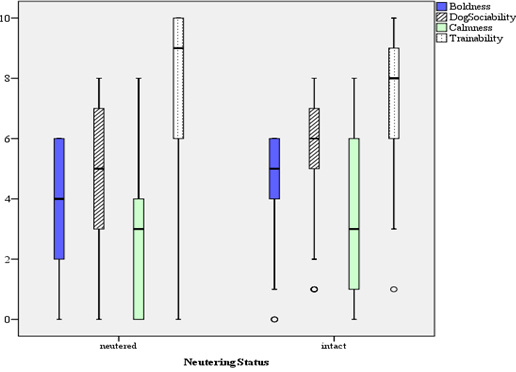

The results of the BUDAPEST Questionnaires for the 67 intact and 66 neutered males reveal that the intact males show a higher median for boldness (Here it must be emphasized that in Turcsan et al24 “boldness” is used as one of the 5 factors, corresponding to the factor extraversion, not to the supertrait “bold” of the shy-bold-concept, e.g. in behavioural ecology.) (median=5) than the castrates (median=4) (Figure 6). For the category ‘Sociability to dogs’ the scores of the neutered dogs are also lower (median=5) than the values of the intact males (median=6). Regarding calmness no difference can be noticed between the median values of both the neutered and intact dogs (median=3). The situation is different with the feature trainability. Here, the neutered males have a higher median value (median=9) than the non-castrated dogs (median=8).

Figure 6: Evaluation of the BUDAPEST Questionnaires Regarding 67 Intact and 66 Neutered Dogs (n=133 dogs)

Case Studies

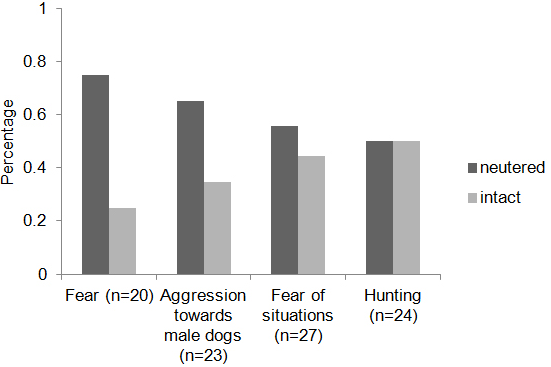

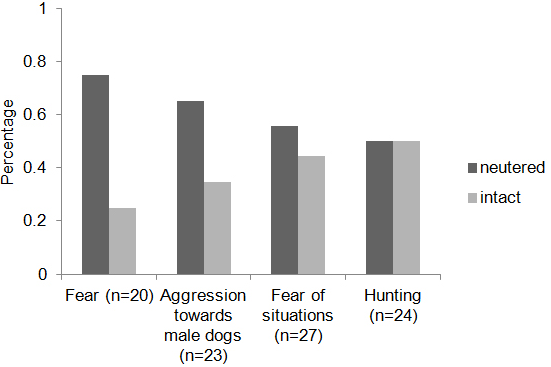

A percentual comparison of intact and castrated males regarding behaviours selected from the anamnesis questionnaires is shown in Figure 7. The biggest difference between castrates and intact males can be found for fearful behaviour. Here, 15 of the 17 castrated dogs show anxiety during the walk. By contrast, this has been noted only for five intact dogs. Aggression towards other dogs can also be counted for more castrated and less intact dogs. Twelve intact males show fear of situations and among the castrates 14 exhibit such a behaviour. Hunting behaviour occurs to the same extent in the castrated and intact males.

Figure 7: The Percentage of Selected Behaviours of 34 Questionnaires of the 54 Case Studies (n=94)

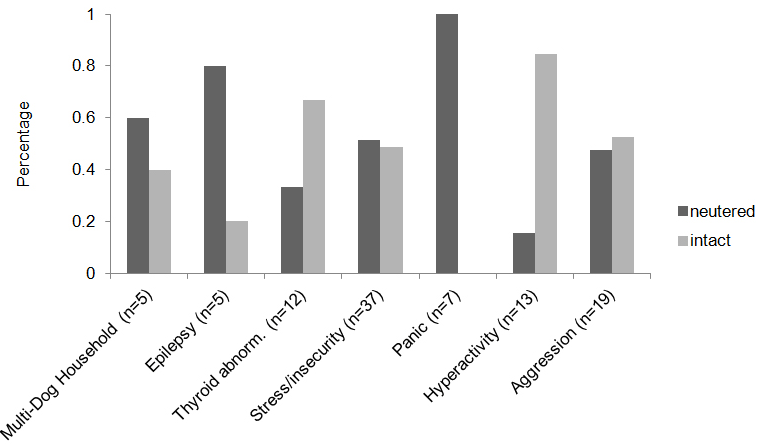

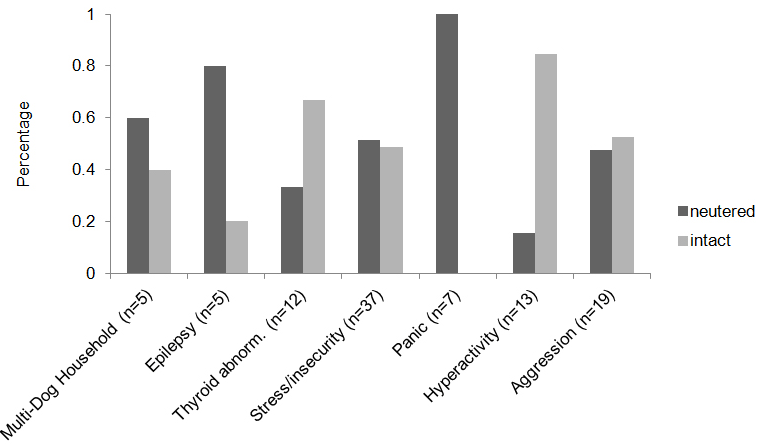

The reasons of dog owners giving rise to contact Udo Gansloßer and Sophie Strodtbeck are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Comparison of Reasons for Seeking Council Given by Owners of Neutered and Intact Male Dogs (n=133 dogs)

Concerning multi-dog household, there are more owners of castrated dogs than owners of intact males, who decided to get a behavioural medical recommendation. Epilepsy can also be noticed for more intact than neutered males and the thyroid gland represents the reason for three castrated and for twice as many intact dogs. Stress or insecurity is indicated for both ten neutered and intact dogs. Panic can be noticed only for neutered and for none of intact males. Hyperactivity is shown significantly more by intact than neutered dogs. Finally, aggression can be recorded more frequently in the castrated males.

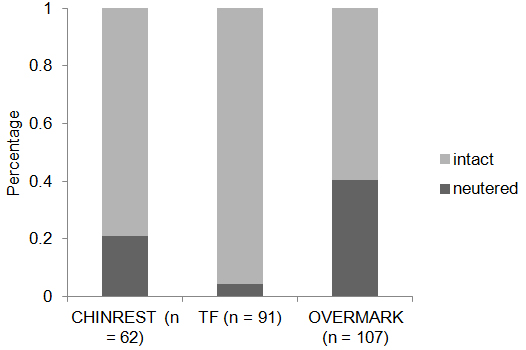

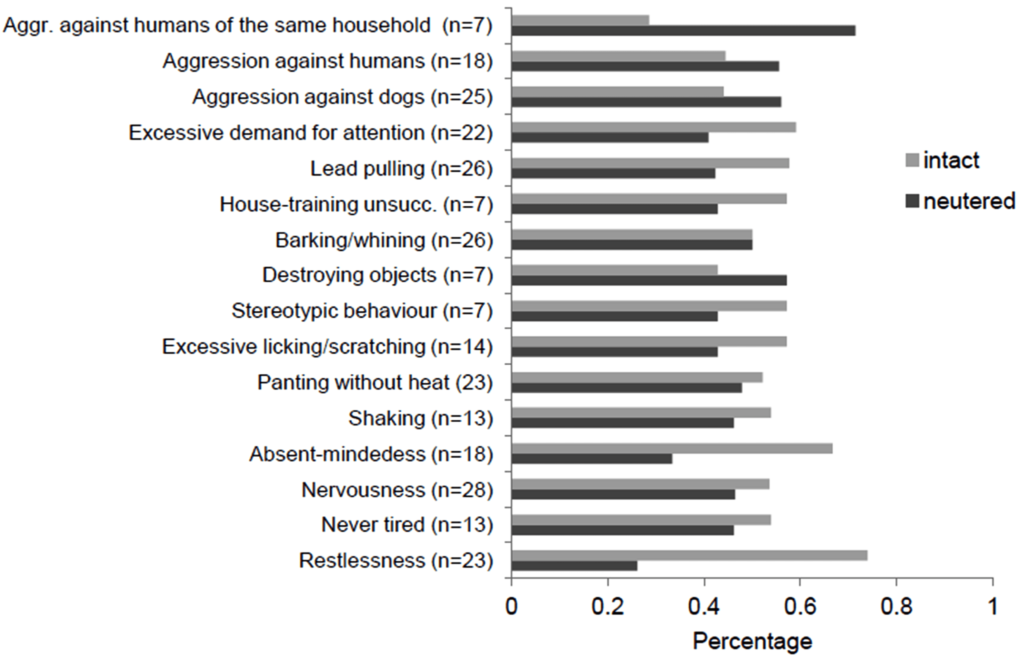

A graphical analysis of 54 completed Einzelfelle questionnaires revealed that of 16 considered behaviours, 11 were shown more often by intact males (Figure 9). However, barking and/or whining can be noted equally in neutered and intact dogs, and neutered males also tend to be more aggressive towards both humans and humans of the same household as well as towards dogs. Destroying objects is also noticed for more castrates than intact ones.

Figure 9: Percentage of Neutered versus Intact Males Affected by Several Investigated Behaviours (n=17 dogs)

DISCUSSION

Video Analyses

The aim of this study was to gain further insight into the effects of neutering on a male dog’s behaviour by comparing the social behaviour of neutered and intact animals in an observational part as well as by evaluating questionnaires submitted by dog owners.

We found significant differences among several behavioural traits (e.g., molest, sniffing the anal region, licking genitals, tootchchatter, sniff genitals, posing, T-Formation, chinrest and nosing), verifying our first hypothesis, which implies that there are certain behaviours which are shown in a different frequency by neutered and intact male dogs. In particular, these significant differences show that the neutered dogs are more likely to receive ‘sniffing of the anal region’ from intact males. Dogs, like many other mammals, use pheromones and other scents for social differentiation. The sniffing of the “anogenital” region and of the head as well as the close following of a conspecific are summarized as an olfactory inspection.27 In canids, three functions of anal gland secretion are distinguished: on the one hand, the sexual attractiveness is taken into consideration and on the other hand, it is associated with individual recognition and territorial delineation. They are also assigned an alarm function.28

The fact that castrated male dogs are more frequently harassed and sniffed, and that their genital and inguinal area are more frequently examined by the intact males, indicates a possibly increased attractiveness of the castrated males in relation to the intact males. Preferably, the genital region of bitches or faeces is intensively inspected and also licked in the estrus phase. Usually, animals in a relaxed mode allow each other to smell this region.25 In our video recordings, however, the castrated male dogs did not appear to feel comfortable and the resulting stress can be illustrated by the lateral placement of the ears of the castrates, which also represents a significant difference. According to the ethogram, the ‘ears pricked sideways’ represents an advertising behaviour on the one hand, but it also occurs when a dog is stressed.

The tooth chattering is probably for the most part in a sexual context, since it occurs within the video recordings predominantly during the sniffing of the genital or inguinal region. This behavioural pattern is also described as nibbling from the male, which examines the female genital area. Thereby the incisors are quickly thrown together.25

In the case of confident/assertive behaviour it can be shown that the second hypothesis (‘Neutered males show confident behaviour less frequently than intact males’) is also verified regarding the behaviour of chinrest and T-formation. Despite the fact that some of the neutered dogs are older than the intact dogs, the latter appear more sovereign in relation to the neutered ones.

The T-formation is often used by males who approach bitches in their heat. In this case of our study, the intact males approach the neutered dogs more frequently, which again gives an indication for the increased attractiveness of the castrated males concerning the intact dogs. This formation is also related to assertive behaviour, in which case the self-confident animal occupies the crossbar position.25

The behaviour pattern ‘chin rest’, as found e.g., by Dopfer29 in foxhounds, does not necessarily have a connection to dominance as a social relationship. This confirms our data that it can also occur in the context of assertive behaviour and is also an approach. On the basis of the video recordings, more intact than castrated males rested their chin on the neutered dogs, and consequently appear more confident in their behaviour than the neutered dogs. Testosterone is associated with anxiety, and men with low testosterone levels are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, which may be decreased by a treatment with testosterone.21 An important aspect probably explaining the uncertain behaviour of the neutered dogs is the lack of testosterone.

The differences between sending and receiving of social behaviour coincide with the above-mentioned results, because here again the intact dogs are sending social behaviour more frequently than the castrated males. When a specifiatc signal is sent, it leads to a specific response by the receiver, as long as it has been received correctly. Methodically, however, there is the problem that not every communication taking place between animals is automatically recognized as such by human. It can sometimes happen that a signal is not understood by the receiver or deliberately ignored and thus it is overlooked as a real signal, since the reaction is not visible or does not occur as expected.30

At overmarking, even the castrates show this behavioural pattern more frequently than the intact dogs but no significant difference can be made in this regard. This behavioural complex is dependent on testosterone, in which the urine of an intact bitch is over-marked by the intact male. However, it is important to distinguish whether a male “directly hits the brand of his or her forerunner or beneath” and the latter is independent of testosterone.31

Testosterone probably does have an important inpact on the urine composition. In a study by Raymer et al28 on the chemical composition of the urine in canids, it was found that certain substances were not present in the urine of the castrates. By treatment with testosterone, however, the neutered males had the same concentration of these substances as the intact males. But the responsible mechanism of the hormones could not be clarified in the study so far. In another study, the urine composition of the wolf and its results indicate that testosterone administration in castrated males causes the formation of certain components associated with intact males, while at the same time decreasing the concentration of other substances that are associated with neutered ones and females. This again emphasizes the hormonal influence on certain chemical fragrance components, which are important for the communication. In addition, the observation that almost two thirds of the investigated behaviour patterns were observed longer or more frequently by intact males might point towards them being more socially active in general. An increase in sample size might offer more information in that field. Furthermore, the fact that there are no significant differences in those behavioural patterns (like mounting, overmarking, urinating with raised leg) between the neutered and intact dogs, that are the most common reasons for neutering, shows that there is no change or improvement in these behaviours.

Questionnaires

Looking at the results of the questionnaires, it can be noted, that the neutered dogs appear less socially to other dogs and also less calm. In the behavioural category ‘Boldness’, the higher score of the intact males indicates that the intact dogs also react more relaxed and emotionally stable in stressed situations than the castrated dogs (Here it must be emphasized that in Turcsan et al24 “boldness” is used as one of the 5 factors, corresponding to the factor extraversion, not to the supertrait “bold” of the shy-bold-concept, e.g., in behavioural ecology.). The intact dogs reach a higher score in the category ‘Dog sociability’ and also a higher median, whereby giving a lower tendency for mistrust and fighting than the castrated males. In contrast, the neutered dogs seem to have a higher tendency for bullying and aggressive conflicts. At ‘Trainability’, the overall score of the neutered dogs is higher than that of the castrated males, so there seems to be an improvement in training a dog, when it is neutered. Nevertheless, all these results are based on the observations of dog owners and cannot be regarded as completely neutral and objective observations.

Case Studies

The results of the case studies regarding to specific behaviours indicate that the castrated male dogs show more anxiety on walks than the intact ones. Likewise, there are more neutered than intact males showing aggressive behaviour against other males. In addition, more castrated dogs show fear of situations. In an article of Farhoody and Zink, published in 2010,32 which is based on a master thesis, the results from the surveys are summarized with a sample size of more than 10,000 dogs. This study indicates that dogs develop a more anxious behaviour after neutering, because they are denied their ability to explore their surroundings and to process the experiences of fear in a correct manner. Among other things, it was also pointed out in our project that castrated dogs were more aggressive, more anxious and more excited than the intact dogs. The data from the study mentioned above showed significant correlations between a castration and increased aggression, anxiety and restlessness, regardless of the age at which the castration was performed.31

Nevertheless, there are studies being contrary to our results. These are related to a decrease or disappearance of behavioural problems in 74% of male dogs after neutering33 or to behavioural improvement on aggression toward humans is approximately 25% of adult dogs after gonadectomy.34 Some discrepancies between our findings and those of e.g., Zink et al3 on the one hand, and data by Heidenberger and Unshelm33 and Neilson et al34 on the other hand, who found that some forms of aggression might be reduced by neutering, may be explainable by the fact that aggression is not a unique behavioural system with one common underlying motivation, physiological causation or evolutionary function but a reaction style that can be caused by very different underlying motivations, previous experiences or stimuli.37

With regard to the increasing rate of castration with the aim of changing undesired behaviour, some facts should be kept in mind: firstly, which behaviours are impaired and then: What is the probability that a specific behaviour is really influenced. On the other hand, the dog’s experiences before a castration also play a role in maintaining a behavioural pattern after neutering. Furthermore, the differences between the different breeds should also be considered.35

Also striking is the difference in hyperactivity between the neutered and intact dogs. Here it is indicated for more intact than castrated males. The reason for this could be that the castrates might appear unenthusiastic or are generally less active. Niepel5 describes in her book that some owners (5%) stated that their dog was less active and some (13%) said he had become more lethargic. She is of the opinion that via neutering there is a tendency for changing the dog’s activity, but not being clear in which direction. Thus, a male is not automatically quieter by a castration.5

Regarding aggressive behaviour, it is noticeable that the castrates are more likely to exhibit some of this behaviour than the intact males, which in turn supports the observation that not all types of aggression can be influenced positively by a castration.5 In more neutered than intact dogs, other reasons are listed, and some of them, such as aggression against people, in the same household, stereotypes, nervousness, panic at loud noises and sensitivity towards emotions (meaning emotional instability) again indicate the behavioural consequences of a castration, also supported by Zink et al3 in castrated Vizslas. Regarding stress hormones again, as already described in the introduction, it becomes clear that fear-related aggression is controlled by cortisol and testosterone is eliminated as an inhibitor by a castration.36 Finally, aggressive behaviour is a multi-functional category, thus as a diagnosis it would have to be much more specified. Archer37 distinguishes at least three main categories of aggression, i.e., self-protective, parental and competitive, and only some parts of the latter category are influenced by gonadal hormones.

All these results suggest the aspect of the placebo effect in which the owners after a castration could have expected a change in a specific behaviour in some way, and possibly estimate their neutered dogs as positively changed in this behavioural pattern.35 Also, at the end of adolescence the undesirable behaviour might decrease anyway, regardless of previous castrations.

Various problems may occur in such a study. During the recording sessions, it was not possible to have all dogs present on all occasions. It cannot be excluded that the group composition affects individual behaviour in such a trial. Observed differences in behaviour might therefore also be connected with the absence of a group member of the difference in neutered/intact ratio. Also, dog owners were present during the recordings, which might have affected their dogs’ behaviour. Indeed, some owners intervened during the trials when their dog showed behaviour they judged as overly aggressive or undesirable.

CONCLUSION

The results do not automatically lead to the conclusion that all neutered dogs are more frequently molested than intact males, but a clear tendency is evident that neutered dogs differed in their social behaviour from intact males. One important point could also be the mean age differences between the dog groups, which can mean a limitation of interpretation of social behavioural differences. The results may perhaps be different if the dogs were of the same age.

The results of the Budapest questionnaires and also those of the case studies confirm this thesis. Neutered dogs are more likely to become more anxious and insecure, which is already supported by other research.3 This aspect, as well as animal welfare, should never be disregarded before deciding for a castration.5

The knowledge to be gained is very important for present and future dog owners as well as veterinarians with particular reference to the fact that neutering of dogs has become part of ‘responsible ownership’ in many countries, which according to our results might not be so responsible at all, at least not in all cases.

Understanding long-term effects of the procedure on dog behaviour will be essential for deciding whether or not to neuter a dog, especially since it is often done not to prevent breeding but precisely to change behavioural aspects of a pet.5,16 Even now we could go so far as to advise dog owners against neutering with the intent to correct undesired habits because the lack of verifiable difference in and of itself is enough to question the justifiability of such a drastic intervention, at least until more information can be provided on the behavioural changes induced by gonadectomy. This paper may serve as a forerunner to follow-up studies looking at specific aspects of social behaviour in intact and neutered dogs.

In order to gain a broader view into the subject of castration and its consequences with regard to social behaviour, a comparison with an analysis of bitches would be desirable and so we are in a process of conducting a research on neutered bitches with a parallel study design, which will be published in the future.

In the end, both males and females are always dependent on the decision of the owners, and these should not decide imprudently. The health and well-being of the dog should always be a priority. Therefore, veterinarians should also provide the dog owners all possible alternatives to a castration in order to get the most appropriate decision for the dog.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the support of this project from the “Georgsmarienhütte” dog school from Nathalie Winter (Osnabrück, Germany), from the “El Perro” dog school from Petra Perner and Frank Grelle (Lenzburg, Switzerland), from the “Dog Centrum” from Sabine und Dietmar Meyer (Fürth, Germany) and from the “Frei Schnauze” dog school from Nadia Winter (Karlsruhe, Germany). We also thank all the members of our mammalian behaviour study group for helpful discussions and advises and Ms. Sophie Strodtbeck for her part in devising and conducting the “Einzelfelle” consultancy. This project was first presented as a contributed talk during CSF 2016 at Padua; we thank all the participants in the discussion for clarifying remarks.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest whatsoever.