CASE

A 43 year old Caucasian female presented to the Emergency Department with a left shoulder injury after falling from a “mini-barstool” which she was standing on to reach an overhead shelf. The mechanism was unclear as the patient did not remember what happened. She did remember the fracture occurring and the onset of severe pain with inability to move her arm immediately after the fall. Her past history was remarkable for mental health issues and illicit drug use including crack cocaine and marijuana. Physical examination was remarkable for the patient holding the involved extremity in an adducted, internally rotated position by supporting it with the contralateral upper extremity. Additionally, puckering of the skin along with ecchymoses was noted over the proximal anterior upper extremity (Figures 1 and 2). Radiographs of the injury demonstrated a comminuted fracture of the surgical neck of the left humerus. (Figure 3) Orthopedic evaluation of the patient was accomplished in the emergency department. Because the skin dimpling resolved with gentle traction in the emergency department, the patient was placed in a cuff and collar and discharged with instructions to do no weight bearing of the left upper extremity and to follow-up with orthopedics in one week. Over the next several weeks several emergency department visits occurred for uncontrolled pain and medication refill requests. There were also several follow-up evaluations at the orthopedic clinic. Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF) was subsequently planned but was canceled on the day of surgery because the patient’s urine drug screen was positive for cocaine.

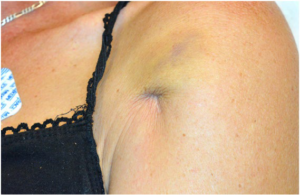

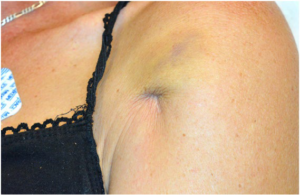

Figure 1: Puckering of the skin associated with a surgical neck fracture of the proximal humerus.

Figure 2: Close up of the puckering and ecchymosis of the skin.

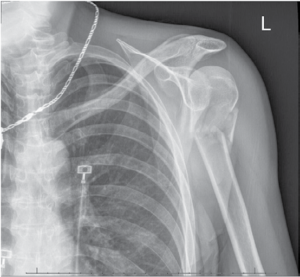

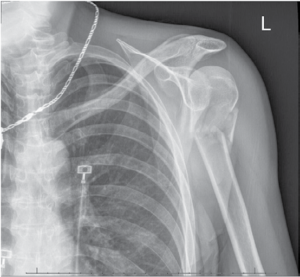

Figure 3: Comminuted fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus.

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the proximal humerus are reportedly the second most common fracture type of the upper extremity and the third most common fracture after hip and distal radius fractures in patients older than 65 years.1 Most often, non-unions of the proximal humerus involve two-part fractures at the surgical neck region.2,3 This patient’s fracture based on the Neer classification system of proximal humeral fractures was a comminuted two part fracture of the surgical neck.4

The pucker sign is a rare finding in association with fractures. Skin puckering has previously been described with tibia fractures, clavicle fractures and supracondylar humeral fractures. In pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures of the extension type the distal spike of the proximal fragment buttonholes through the brachialis muscle to cause the skin puckering. Only five published reports of skin puckering with proximal humerus fractures could be found in an extensive search of the PubMed database.5-9 The published reports consistently showed that the skin puckering sign was consistently associated with marked displacement and soft tissue interposition. (Figure 2) And, a majority of patients with this finding appear to require open reduction and internal fixation because of the soft tissue interposition. Skin puckering occurs when the distal fragment buttonholes through deltoid muscle and comes to lie in the dermis. These findings would suggest that there is a significant force caused by a marked displacement at the fracture site. In a 2008 article, Alshryda et al claimed to be the first to report this clinical finding with a proximal humeral fracture.5 In a 2011 article by Robinson et al, patterns of skin injury were described in 16 patients with proximal humeral fractures. Ten of the 16 patients had skin penetration or open fractures.6 The other six had fracture fragments penetrating the muscular envelope to lie subcutaneously producing either early skin tethering (two patients) or delayed skin penetration and sinus formation (four patients).6 Again, open reduction and internal fixation was the preferred treatment for these patients.6 Another author reported that skin puckering was an uncommon sign associated with proximal humerus fractures and that it was helpful in the diagnosis and in determining the course of treatment.7 Furthermore, it was acknowledged that devastating soft tissue injury could occur if the fracture is not immediately reduced.7 In another single case report claiming to be the second report of skin puckering with a proximal humeral fracture the distal fragment had buttonholed through the deltoid with soft tissue interposition causing the skin puckering.8 This patient’s skin dimpling could also not be relieved by manipulation under sedation and open reduction and internal fixation was required. Jindal et al reported two patients with skin puckering, ecchymoses and surgical neck fractures.9 At surgery both of these patients had the proximal part of the shaft fragment buttonholed through the deltoid muscle. Fracture alignment could only be accomplished after reduction of the buttonholing. The fractures were fixed with multiple Kirschner wires.9 However, it is also clear that the skin dimpling can be resolved with manipulation alone in occasional patients. In this report our patient’s skin puckering was relieved by applying gentle axial traction. The immediate release of the dimple and improvement of skin discoloration was noted. Consequently, initial attempts at reduction of the skin dimpling by gentle traction on the humerus are recommended.

CONCLUSION

Skin puckering or dimpling associated with an underlying humeral surgical neck fracture is a rare sign that most commonly is associated with a buttonhole injury of the deltoid muscle by distal bone fragments. The associated soft tissue interposition causes the associated skin puckering. The buttonholing event through muscle appears to make many of these fractures irreducible. Evidence from a small number cases and case series suggests that timely management of the soft tissue interposition is necessary to prevent further soft tissue injury and the development of an open fracture. As demonstrated in our case gentle traction can sometimes reduce the deltoid muscle buttonholing as well as the skin puckering allowing the subsequent surgical repair to be planned in a timely fashion.

CONSENT

The author has received the written consent for the publication of this case detail.