INTRODUCTION

Physical inactivity adds a disease burden to society comparable with smoking.1 Though physical activity has far-reaching benefits on health and disease,2,3,4 many adults and children do insufficient physical activity to maintain good health.5 Walking or bicycling to work (active commuting) represents one approach to encourage the population to be more active.6 At an individual level, active commuting is correlated with numerous positive health outcomes, including cardiovascular benefits,7,8,9 a reduction in all-cause mortality,10,11 and reduced obesity.12

In spite of these health benefits, in North America only a small proportion of individuals use walking and bicycling as a mode of transport. In Canada in 2006, 6.4 percent of workers walked to work, and just 1.3 percent of workers bicycled to work.13

Factors determining whether a person participates in active commuting are complex; variables such as improved esthetics, the presence of sidewalks and bicycle lanes, and workplace supports are associated with an increased likelihood of active commuting.14-18

Other studies have reported that personal and psychological factors play a more important role than environmental factors.19,20 High self-efficacy,21 positive intentions, and strong habits22,23 are all associated with active commuting. Barriers include lack of fitness, lack of confidence in abilities24 and perceived time and distance.25

Given the health benefits, healthcare providers are well positioned to recommend and promote active commuting. Yet, there have been no studies to our knowledge that assess the role of primary healthcare providers in increasing population levels of this physical activity. Quantitative studies focus on individual variables and are limited in their ability to address all of the complex and interrelated factors associated with the behavior of active commuting.26 To address these many interrelated variables, we conducted a study that qualitatively explored the barriers to active commuting and how healthcare providers could be involved in addressing these barriers for their patients. The study was done in a primary care population who were under the care of a healthcare provider (and therefore within reach of a healthcare intervention).

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative research study using 5 separate onehour focus groups of up to 5 people over a period of 4 months at McMaster Family Practice in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Approval was obtained from the McMaster University Research Ethics Board.

Sampling

Participants were recruited from a list of current patients aged 18 to 65 years old that had been randomly generated by the electronic medical record (EMR) system within the practice. Possible participants were telephoned by a member of the research team (RW, SG) to assess eligibility and willingness to participate, and to clarify status as an active or non-active commuter. Patients were informed that if they did not wish to participate in the focus group, their medical care would be unaffected. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be patients at McMaster Family Practice, currently working or attending school, and residing within a 10 kilometre distance to walk or bicycle to their place of work. Exclusion criteria were if patients had any selfidentified physical limitation to walking or bicycling.

The active commuters and the non-active commuters were given separate focus groups to allow for adequate space and time for the unique viewpoints of each group. Focus groups were carried on until theme saturation was met. We aimed for up to 5 participants per focus group.

Facilitation Process

The focus groups were held in a semi-structured format to allow for free discussion within defined topics. Our focus group questions were developed to inspire discussion in an open-ended manner:

• Why do you choose driving to work instead of bicycling or walking (or vice versa)?

• What barriers do you face in bicycling or walking to work?

• How could you overcome those barriers?

• How can healthcare providers help you to start or continue walking or bicycling to work?

Data Collection and Analysis

Focus groups were facilitated by RW and SG. The focus groups were recorded using a digital recorder and transcribed. A grounded theory approach was used to analyze the data because it allowed for data collection and analysis to occur simultaneously and for theories to be generated freely from the data without a preconceived hypothesis.27 All 3 authors read the transcripts independently and devised an initial list of themes and subthemes. These themes were closely examined, negotiated, and consolidated at a series of meetings involving all members of the research team. Upon further analysis, these themes and subthemes were then organized into broader themes upon re-application with the original transcripts. Consensus was obtained a final list of coding themes was generated. Recruitment for new focus groups concluded when a saturation point for all themes was reached and no new themes were being generated.

RESULTS

A total of 5 focus groups took place between May and August 2012. Three groups for active commuters and 2 groups for nonactive commuters were held with 3 to 4 participants at each session. A total of 17 participants were recruited (11 active commuters and 6 non-active commuters) before a saturation point was met.

Participant Characteristics

Most of our participants were Caucasian and between 27 and 65 years old with a mean age of 56 (Table 1). Women comprised 47% of the overall sample and made up 33% of active commuters and 66% of non-active commuters. Participants had high levels of education with 16 out of 17 participants (94%) having achieved a college education or higher.

Table 1: Characteristics of study participants (n=17).

|

Participant Characteristics

|

Not Active Commuters (n=6) |

Active Commuters (n=11)

|

|

Age (years) (mean±standard deviation)

|

56±6.7 |

49.5±14.8

|

|

Ethnicity

Caucasian

Blank

Non-Caucasian

|

6 (100%)

0

0 |

7 (63.6%)

2 (18.2%)

2 (18.2%)

|

|

Gender

Female

Male

|

4 (66.7%)

2 (33.3%) |

4 (36.4%)

7 (63.6%)

|

|

Educational status

Elementary

Secondary

Tech school or college University or higher

|

0

1 (16.7%)

1 (16.7%)

4 (66.7%) |

0

0

1 (9.1%)

10 (90.9%

|

|

Marital Status

Single

Living with a partner Separated or divorced

|

1 (16.7%)

4 (66.7%)

1 (16.7% |

4 (36.4%)

7 (63.6%)

1 (16.7%)

|

|

Number of children

0

1 ≥ 2

|

3 (50%)

0

3 (50%) |

6 (54.5%)

1 (16.7%)

4 (36.4%)

|

|

Employment status

Working

Attending School

|

6 (100%)

0 |

10 (90.9%)

1 (9.1%)

|

|

Annual income

<20,000

20,000-50,000

50,000-80,000

>80,000

|

2 (33.3%)

2 (33.3%)

1 (16.7%)

1 (16.7%) |

0

6 (54.5%)

5 (45.4%)

0

|

Barriers to Active Commuting

The research team organized the barriers identified by participants into 3 main thematic categories: internal, external, and cultural.

Barriers such as inconvenience were labeled as internal barriers during the thematic analysis if they occurred at the individual and psychological level. External barriers were defined as those that happened outside in the built environment, such as bicycle lanes and workplace accommodations. A barrier was categorized as cultural if it occurred on a larger, societal level. Table 2 summarizes the barriers identified above.

Table 2: Patient-identified barriers to active commuting

|

Type of Barrier

|

Themes |

Key Points |

Representative Quotes

|

|

Internal

|

Time and Inconvenience

|

Time is a valuable commodity and drivers perceived active commuting as slow and inconvenient.

In contrast, those who walked or bicycled to work saw active commuting as a time saver— functional exercise that saved time otherwise spent on organized physical activity |

“If I drive I’m there in five minutes and I can just start work and I’m done, so it’s hard to…convince yourself it’s a good use of your time to actually walk.” – Female, age 57, drives

“If I ride my bike I come home, I have dinner, I relax. If I have taken the bus or driven my car, then I come home… and then I think okay, I’ve got to go to spin.” – Female, age 58, walks & bicycles |

|

Internal

|

Habit and Routine

|

Driving to work was seen as the “default”—easy and logistically simple. Non-active commuters spoke about the extra work required to change their routine. |

“It’s really easy… to fall back on your default which is get in the car. It’s just simple, it doesn’t take any additional planning. There’s always room for groceries in the back and if it starts to rain you put the wipers on. I mean all of those things is a default that does not require any thought at all.” – Female, age 58, walks & bicycles |

|

External

|

Road Safety

|

A lack of bike lanes and improperly maintained roads were all deterrents to active commuting. Multiple participants were concerned about safety and saw cycling as dangerous. |

“I am not comfortable at all biking in traffic and I have suggested that to friends and family and they have said don’t do it.” – Female, age 57, drives |

|

External

|

Workplace Accommodations

|

Workplace accommodations, such as showering facilities and secure bike shelters, were also cited as motivators. |

“I’ve gone here to my workplace, where do I park my bike? Everybody has a place to park their car but where are the bike racks?” – Male, age 65, walks & bicycles |

|

Cultural

|

Car-Centric Culture

|

European and Asian cultures were perceived as more favorable towards active commuting. In contrast, North American culture was described as a car-centric culture. |

“… my generation I suppose was really wrapped up in cars, the car was the great thing that was, gives your great passage into manhood or womanhood or whatever…” – Male, age 65, walks & bicycles |

|

Cultural

|

Community Design

|

People who drove discussed how community design necessitated a vehicle in many instances. |

“So you know, that, that has to be somehow figured into the mechanism to encourage people to be able to either bike or walk you know, to go and do shopping or whatever without having to you know, resort to a vehicle which just clogs city streets and so on.” – Male, age 50, takes the bus |

|

Cultural

|

Cyclist vs. Motorist Tensions

|

Cyclists and drivers felt distrustful of each other and users of either mode of transportation cited a lack of understanding of the rules of the road. |

“I’ve been honked at and yelled at for riding this close to the curb because I’m slowing traffic down. You know, I could ride in the middle of the lane and slow you down more if you want.” – Female, age 51, walks & bicycles |

THE ROLE OF HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS IN ADDRESSING THESE BARRIERS

Participants outlined several opportunities for physician intervention, including (1) individualized education around the health benefits of active commuting, (2) problem-solving around barriers to active commuting, (3) motivational interviewing, and (4) advocacy. These are outlined in further detail below.

PATIENT EDUCATION ON THE BENEFITS OF ACTIVE COMMUTING

Participants who actively commuted brought up numerous benefits that motivated them to actively commute. These benefits included mental and physical health benefits, financial savings, and enjoyment of the community and environment. Participants thought that learning about active commuting from their family physician during a clinical encounter would be an effective way to increase physical activity. In particular, patients suggested they would be receptive to hearing about the non-physical health benefits. The key points regarding how physicians could approach these conversations are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3: Summary of benefits of active commuting for patient education

|

Benefits of Active Commuting

|

Key Points for Physicians |

Representative Quotes

|

|

Physical Health

|

More information on health outcomes beyond weight control might encourage commuters to be more physically active.

Physicians can remind patients that exercise does not have to be at a gym |

“If you can identify that [active commuting] counts as exercise then it’s an option. Sometimes people think that exercise has to be at a gym or has to be very formal [with machines], or without a purpose.” – Female, age 33, walks & bicycles |

|

Mental Health Benefits

|

Participants described the negative effect that being in a car had on their mood and how much better they felt walking or bicycling instead.

Both active and non-active commuters brought up transition time between work and home as a particularly attractive benefit to active commuting. |

“I know my emotional state improves with [exercise]…so it’s worth doing. And rarely in a car, I mean I never feel emotionally relieved, improved, insightful, or anything in a car… I don’t feel as angry when I’m riding a bike.” – Male, age 59, bicycles |

|

Financial Benefits

|

Participants discussed the cost of car ownership, insurance, and gas in detail, as well as the high cost of parking and the cost of gym memberships. Financial savings are an attractive incentive to begin active commuting |

“You are going to be paying 45 bucks a day for your membership to go and stand on a treadmill, for free you can go outside and walk home.” – Male, age 65, walks & bicycles |

|

Interactions with People and the Environment

|

Active commuting provides time not only to exercise but to catch up with family members or converse with other members of the community.

Active commuters enjoyed the time spent outdoors and used it as a time to stay in touch with the natural environment. |

“[As far as] interaction with the natural world, there is nothing you can do to see how time passes, growing old and to watch the seasons evolve by walking the same street in the same area, from time to time… If you walk by or ride by under a tree you know, that has come into blossom and you can smell that, that’s a stimulation it is terrific that you will not get in a car.” – Male, age 65, walks & bicycles |

PROBLEM-SOLVING AND MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

Even though both non-active and active commuters identified similar barriers, active commuters were much better equipped to problem-solve logistical issues. Participants suggested that physicians might be well positioned to help patients problemsolve. Active commuters suggested that simple solutions such as bringing a spare change of clothes, watching the weather report, and leaving five minutes earlier would solve common concerns people have about work clothes.

To motivate patients, apart from discussing the benefits of active commuting, study participants proposed that healthcare providers could encourage small behavioral changes. Participants suggested that physicians could highlight that patients could choose to walk or bicycle to work just a few days a week and still reap health benefits.

The representative quotes that illustrate these themes are found in Table 4.

Table 4: Themes for problem-solving and motivation

|

Theme

|

Representative Quotes

|

|

Problem-Solving

|

“I know people in our office… will say to me, oh, ‘how can you bike today, it’s so cold’… And the answer is you do the Canadian thing, you put on layers of clothing sufficient to cover today’s temperature and it’s more clothes today then yesterday and if tomorrow is warmer it’s less clothing.” – Male, age 65, bicycles |

|

Motivation

|

“Yeah, I think that’s really important, it’s not all or nothing, you can break it into smaller chunks, more achievable distances.” – Female, age 33, walks & bicycles |

ADVOCACY

Finally, participants suggested that physicians could act as community advocates to promote safe cycling infrastructure, better work and school accommodations, and greater education. One participant suggested that active commuting could be approached in the same manner that public health, government agencies, and individual healthcare providers have approached smoking cessation. In addition to individual healthcare interventions, there could be a role for workplace incentives for active commuters and for increased media attention around the benefits of active commuting.

Participants brain stormed large-scale societal changes for which physicians could advocate. Participants suggested that if cities were designed better, it would be more convenient to actively commute. One participant suggested that doctors focus on pressuring governments to make a more walk and cycle-friendly environment before asking patients for individual change.

These themes and representative quotes are further explored in Table 5.

Table 5: Themes for physician advocacy

|

Theme

|

Representative Quotes

|

|

Advocacy to Government and workplace

|

“For many years now… the anti-smoking information that has been available out there is working, the laws are changing… People are quitting smoking; the percentage of people that smoke now as opposed to 20 years ago is dramatically different. And that’s because there was so much information out there and healthcare providers also contributed… And there were incentives in the workplace to [quit smoking]… They really did a lot [with] public advertising and information.” – Female, age 50, drives |

|

Advocacy for Improved Urban Design

|

“So I mean if a lot of those services were a little bit you know, closer in to where the people are living [I would consider active commuting]… So you know, that, that has to be somehow figured into the mechanism to encourage people to be able to either bike or walk…” – Male, age 50, takes the bus |

DISCUSSION

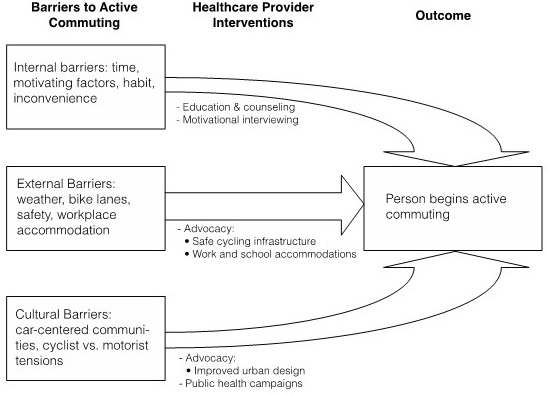

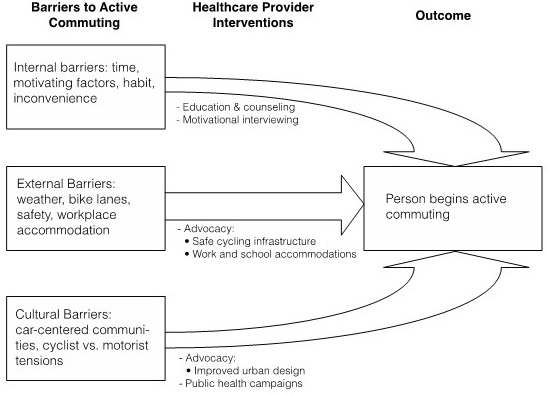

Through this qualitative study, we identified 3 main kinds of barriers to active commuting in attendees of a family practice—internal, external, and social. The patient-identified barriers helped shape and inform the discussion of healthcare provider intervention. Indeed, the types of interventions participants identified could be categorized into the same main categories. The barriers cited by members of a family practice in this study were consistent with barriers cited by members of the general public in prior studies.24-28 Our study population was different in that all participants were known to have easy access to a physician. The relationship between barriers and other determinants of active commuting is complex. Ogilvie et al29 have developed a framework to understand the relationship between the multiple determinants of active commuting. Up until now, the role of healthcare providers in assisting patients in overcoming these barriers to start active commuting has not been studied. We sought to bring a patient-centered approach to healthcare provider intervention. Based on the themes of barriers and interventions, we have developed a framework to suggest the ways in which healthcare providers might intervene on modifiable barriers (Figure 1). We discuss the framework in detail below.

Figure 1: Barriers to active commuting and corresponding healthcare interventions

Healthcare Intervention on Internal Barriers

Participants proposed that they would be open to hearing from their physician one-on-one about active commuting. Physicians could address the internal barriers on an individual basis through education, support, and motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing can be defined as “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change”.30 It may include educating patients in a clinical encounter to consider active commuting as a form of exercise; helping patients become motivated; or problem-solving solutions to patient-identified barriers. As an example, if a patient would like to actively commute for exercise but feels that he or she does not have the motivation nor the time, it may be helpful to use motivational interviewing to challenge his or her way of thinking. Motivational interviewing has been shown to be effective in changing health behavior,31,32 and this form of intervention is the most readily accessible intervention to primary care physicians.

Increasing physical activity through active commuting could be part of a comprehensive management plan for patients with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity. Above and beyond the physical health benefits of active commuting, there were numerous other benefits discussed by participants including mental health improvements, financial savings, and interaction with the community and the environment. Participants were receptive to hearing about the “non-physical” benefits of active commuting and this information could be discussed in various clinical encounters.

Healthcare Intervention on External Barriers

Intervening on external barriers has the potential for a large population health impact. Healthcare providers can act as advocates to promote safe cycling infrastructure and better work and school accommodations. The Ontario Medical Association (OMA) is an example of a physician-led organization doing such advocacy work. The OMA has recommended that the Ontario government increase separated bicycle lanes and make cyclistvehicle education a component of the Ontario Drivers’ Manual.33 Family physician-led organizations could perform similar advocacy work, as they are a well-respected source of information for policy makers and already do such work on other issues.34

The voice of individual family physicians may be beneficial in their community of practice where they have specific insight into their patient population needs. For example, family physicians could speak to their city council in support of bicycle lane additions. Being a health advocate for their patients and communities is one of the seven roles of a family physician identified by the Canadian College of Family Physicians.35 Healthcare providers can also provide information and research to encourage private companies to invest in workplace active commuting infrastructure.

Much like the campaign for smoking cessation, a variety of stakeholders are needed to fully address systemic issues. These stakeholders may include citizen groups, employers, city councils, and government officials.

Healthcare Intervention on Cultural Barriers

Creating a culture of walking and bicycling requires not only the removal of barriers, but also a re-imagining of city layout to make active commuting an easier option. Physicians could advocate to city councils for an urban design that makes walking to work and other important destinations such as the grocery store logistically possible.

Physicians can also intervene to promote an active commuting culture through public health education campaigns Media advertising could be used to promote the health benefits of active commuting on a large scale and to improve safety on the road. One such initiative is the “Share the Road” campaign36 that creates television ads to improve the relationship between drivers and cyclists. Media campaigns can be important tools but they need to be done while addressing internal and external barriers. As illustrated by the success story of the anti-tobacco movement, multi-pronged interventions are likely needed to prime the public so that they are open to receiving information from media campaigns.37

LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

The study provides an in-depth exploration of the barriers that family practice patients face in active commuting. In addition to providing the first qualitative information about the role of primary healthcare providers in active commuting, we provide a framework of possible areas of intervention.

This study has several limitations. The nature of qualitative studies makes it difficult to generalize the results to a larger population. The number of active commuters participants and non-active commuters participants were not equal in the study. Since all participants were patients at McMaster Family Practice, problems and solutions that are specific to other jurisdictions would not have been captured. The majority of participants were Caucasian and barriers of other ethnic groups may not have been represented. Further qualitative research is required with an emphasis on reaching out to ethnically mixed communities. In addition to soliciting more patient perspectives, it would be helpful to gain information through the lens of healthcare providers or other agencies involved in promoting active commuting. Quantitative studies assessing patient barriers to active commuting and areas of physician intervention would help confirm the patient-identified barriers and proposed physician interventions.

Next steps after identifying interventions would then be to assess their efficacy. This research may include studies that look at the outcome of promoting active commuting through education, counseling, and motivational interviewing. Previous studies have looked at motivational interviewing for increasing physical activity in general and this avenue seems to be a promising wayto promote health behavior change.31,32

CONCLUSION

The patient-identified barriers to active commuting fell into 3 main categories: internal barriers, external barriers, and cultural barriers. Correspondingly, there were physician solutions found for each type of barrier. Participants suggested numerous opportunities for healthcare provider intervention, including individualized education regarding the health benefits of active commuting, problem-solving around barriers, motivational interviewing, andadvocacy. Physicians can use the information provided in this study to help guide a one-on-one discussion with a patient to address internal barriers. Physicians can also use this information to advocate for the removal of external and cultural barriers.

Healthcare providers are one of the many stakeholders required to create a comprehensive strategy to get the population more physically active through active commuting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the study participants, supporters, and funders. Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC) and the Ontario Public Interest Group (OPIRG)–McMaster provided study funding, and the McMaster Department of Family Medicine provided support for the project.

FUNDING SOURCES

Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC) and the Ontario Public Interest Group (OPIRG)-McMaster funded the study. The funding bodies had no part in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funding for manuscript publication was provided by MEC. This project was completed as part of a research project for the Family Medicine Residency Program, Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RW conceived of the study and its design, participated in the data collection, interpretation, and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SG participated in data collection, interpretation, and analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. GA contributed to study design and participated in data interpretation and analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONSENT

The participants has provided written permission for the manuscript publication.