INTRODUCTION

As we progress into the modern days of technological advancement, there has been a transition from conservative teaching in classes and in sessions, where one is required to attend these classes face-to-face to enable more interaction and experience such learning. This, in general, has been the way we have been approaching the learning environment, regardless of the topics being trained. The same thing can be said about parenting programs. More online platforms are being created and utilized to provide parents with the information and support they need to help them become better parents for their children.

A meta-analysis looking at online programs as a tool to improve parenting looked at 7 programs implemented throughout the years 2000-2017 and showed positive effects of the program for both parent and child, change of attitude and behavior, and diversified parenting styles.1 The main purpose of providing such resources is to make the program more accessible to parents who would otherwise need to travel to a service venue, thereby alleviating often-cited pragmatic barriers to participation in parenting programs.

There have been studies looking at online parenting support such as interactive web-based programs that offer various types of online communication, for example, chat, confidential chat, e-mail consultation, e-mailing lists, discussion boards, and information pages.2 These and other professionally designed parenting programs usually aim to reduce family stress, strengthen parents’ advocacy, and improve parenting self-efficacy and parenting competencies by delivering resources for mutual support, offering professional consultation, and providing parent training.2 According to the same study, chat and e-mail are text-based methods of delivering advice and support. It was noted that online methods require other skills, such as interactive software, to encourage active engagement of participants compared to those required for face-to-face support to, for instance, build rapport, interpret, reflect, confront, and summarize.3,4

Positive parenting is one program that is currently being implemented online, in general, to provide parents with skills that are nurturing, empowering, non-violent, and provide recognition and guidance that involve setting boundaries to enable the full development of the child.5 This was evident with the support of government agencies such as one that was implemented in Spain, although the intervention was not aimed specifically at parents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) children. As such, it has been integrated into some online parenting programs to support parents in managing themselves. This is important because, in most cases where abused children were found, they were not equipped with proper parenting knowledge and skills.6,7

Although many families find great help in online parenting to increase their parenting skills, there are still large gaps in the availability of resources tailored exclusively for parents of children with ASD. Mindfulness as a concept has shown a positive impact on individual well-being, but as a specific psychological approach to improving parenting skills in managing children with ASD, it is very scarce. Therefore, this systematic review aims to bridge that knowledge gap.

METHODOLOGY

This systematic review protocol was designated based on the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search Strategy

Three databases were used to identify the possible literature. These were: Google Scholar, MEDLINE, and PubMed. To build our search queries, boolean operators such as “AND” and “OR” were used. MeSH terms, keywords, and index/subject terms were utilized during the literature search to increase the specificity and feasibility, as well as to capture all the relevant and eligible studies and reviews.

Inclusion Criteria

According to the “Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study (PICOS) Design” framework, the groups of the interested populations were divided into two groups, which were exposure and outcome groups. For the exposure population, it involved parents with ASD or children with special needs, while the outcome population involved the parents. The intervention involved any online parenting education or module being taught or exposed to parents. For the outcome, types of online parenting education or modules are being used as teaching tools for parents that cover mainly general aspects of parenting rather than focusing on understanding and managing children with ASD or special needs.

This literature review included all observational study design literature related to the topic that was published in English and covered the years from January 2011-2021. The keywords used in the database machines consisted of online parenting education or modules, online parenting, parents with ASD children, and parents with special needs children.

Selection Process

The list of titles and abstracts was downloaded and organized using the EndNoteTM program. Another online software, Covidence, was used as a deduplication and screening tool. After removing duplicates, two reviewers sorted the remaining studies to determine their eligibility. The full articles selected were then retrieved. Conflicts were resolved through cooperation.

Data Collection Process and Synthesis

The data from the relevant instruments was collected and extracted by a reviewer into Covidence. The components of data that were extracted involved study detail (author and year), study method (study design, setting, and sample), independent variables (types of exposure), dependent variables (types of outcomes, outcome tool, age at assessment), and results. The findings of the selected studies were presented in a narrative review within the final review.

RESULTS

Literature Search

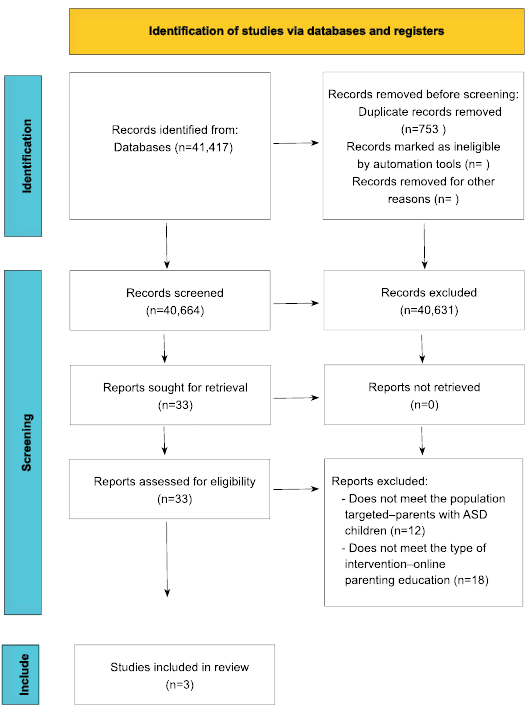

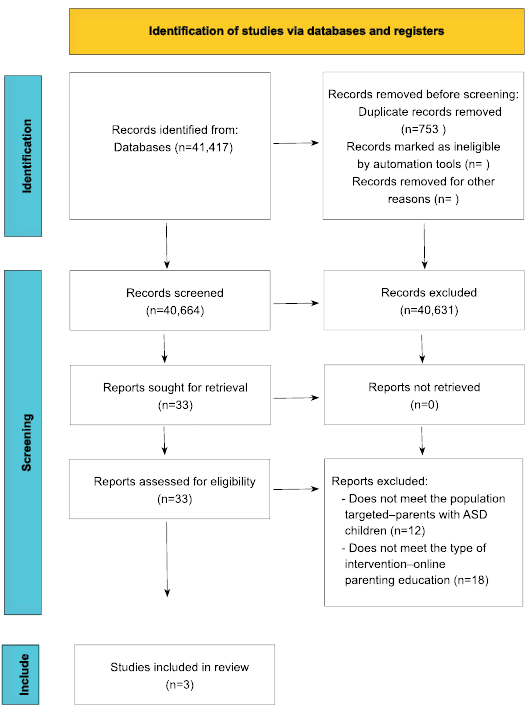

The literature search resulted in 41,417 articles. A total of 753 duplicate articles were removed. After title and abstract screening, 40,664 articles were excluded as those articles did not meet the inclusion criteria, while 33 articles were retained for full-text assessment and assessed for eligibility criteria. 30 out of 33 articles were excluded because the intervention criteria were not met. The remaining 3 papers were included in this systematic review as those papers met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). The literature search is shown in Figure 1.

| Table 1. Characteristics and Findings between Online Parenting Education for Parents with ASD/Special needs Children |

| Study |

Study

Characteristics

|

Exposure

(Online Parenting

Education)

|

Outcome

(Improved parenting practices)

|

Main Findings |

| Types of

Exposure

|

Timing of

Exposure |

Age at

Assessment |

Measuring Tools |

| Sanders et al9 |

RCT, Queensland, Australia

(n=200) |

Triple P

Online Brief |

8-weeks

intervention and 8 months follow-up |

2 to 9-years-old children |

• Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory8

• The Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES)9

• Parenting Scales10

• Behavior Concerned and Parent Confidence Scale11

• Parent Child Play Task

Observation (PCPTOS)12 |

• Child Behavior and Parenting–ECBI

revealed a significant condition effect for child behavior F (2,195)=3.29-3.62, p=0.29-0.039

• TPOL Brief reported significantly lower

intensity and significantly fewer child behavior problems than WLC, with small to medium effect size

• Parenting Style Revealed significant

condition effect F (3, 193)=6.25-8.52, p<0.001.

• Behavior Concern and Parents Confidence, F (2,195) =8.87-10.59, p<0.01. Intervention group reported fewer concerns and more confident at follow up assessment compared to WLC. |

| Padgett13 |

Cohort, US

(n=32) |

Mindfulness parenting |

6-weeks

intervention |

6 to 11-years-old children |

• Interpersonal Mindfulness in

Parenting Scale14

• Mindfulness Attention and

Awareness Scale15

• Depression Anxiety and Stress

Scale-Short Form (DASS-21)16

• Parental Stress Scale (PSS)17

• Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form (SCS-SF)18 |

• Participants in the intervention

condition reported stable mindfulness from T1 to T2 compared to those in the waitlist control condition, whose trait mindfulness went down from T1 to T2. This suggests the intervention condition may have acted as a protective factor against the reduction in trait mindfulness over time.

• Additionally, parents’ subjective reports of their experiences participating in the mindful parenting intervention indicated it was

helpful and promoted change. |

| Hinton

et al19 |

Cohort, Australia

(n=98) |

Triple P Online – Disability (TPOL-D) |

7-weeks

intervention and 3-months follow-up |

2 to 12-years diagnosed with a range of

developmental, intellectual and physical

disabilities |

• Developmental Behaviour Checklist

– Primary Carer version (DBC-P)20

• Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale – Developmental Disability (CAPES-DD)21

• The Parenting and Family

Adjustment Scales (PAFAS)22

• The Client Satisfaction

Questionnaire (CSQ)23 |

• In comparison with the TAU group, parents who completed TPOL-D reported significantly increased confidence in managing their child’s emotional and behavioral problems.

• The ANOVA for parental self-efficacy showed a significant Time×Group inter-action, F(1,87)=13.33, p<0.001, ηp2=0.13, as well as a significant main effect for Time, F(1,87)=14.96, p<0.001, ηp2=0.015, and Group, F(1,87)=6.49, p<0.05, ηp2=0.07.

• The interaction revealed that parents who

completed TPOL-D reported significant

improve-ments in their parenting practices

(such as greater use of descriptive praise, logical consequences and similar strategies) when

compared with the TAU group.

• Parent-reported child behavioral and emotional problems significantly decreased from T1 to T3, perhaps indicating the presence of a ‘sleeper effect’ in regard to this outcome.

• Parents experienced a significant improvement in confidence in relation to managing the problem behaviors of their child from T1 to T3.

• Parents also experienced a significant decrease in dysfunctional parenting practices from T1 to T3. |

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart of Study Selection

Study Characteristics

All studies were randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies published between 2016 and 2020.

Types of Online Parenting Education

All three studies used specific parenting modules to assist parents with ASD or special needs children. These modules were given through an online medium called self-directed learning.

Excluded Studies

Most studies were excluded during the final full review of the paper due to two main reasons: 1) the studies do not meet the targeted population for this systematic review, or 2) the studies did not meet the requirement for the type of intervention used.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this systematic review revealed that an online parenting education program can be an effective tool for improving parenting in families with ASD children. It helps parents decrease dysfunctional parenting; it can also increase parental confidence in dealing with problematic behavior.11

The two main approaches being used in these three studies were positive parenting and mindfulness parenting. Both have different methods of intervention that provide parents with parenting skills to create a positive experience for themselves and their children.

Positive psychology is a branch of psychology that studies human strengths, well-being, and the factors that contribute to a fulfilling and meaningful life. Positive psychology, as opposed to conventional psychology, often focuses on pathology and the treatment of mental disorders and investigates the positive aspects of human experience. It encompasses subjective well-being (SWB) as a key concept in positive psychology, and it encompasses life satisfaction, positive emotions, and the absence of negative emotions.24 Positive psychology, which emphasizes identifying and utilizing character strengths as developed by Peterson and Seligman,25 is a foundational framework in this area. It also explores the many facets of positive emotions and gratitude, whereby it introduces interventions such as gratitude exercises, like a gratitude journal or writing thank-you letters, that have been linked to increased well-being.26 Positive emotions in general are a focus of positive psychology research.

Mindfulness parenting, also known as mindful parenting, is a parenting approach that integrates the principles of mindfulness, a Buddhist meditation practice, with the challenges and joys of raising children. It entails being fully present and non-judgmental in the interactions with the child, cultivating awareness, and responding with intention and compassion to parenting situations.27 Mindfulness parenting encourages mindful communication, which includes active listening and empathic responses to a child’s emotions and needs. This method fosters a stronger bond with the child and contributes to a more nurturing and supportive environment.28 Parental stress and anxiety can be reduced through mindfulness parenting, resulting in more effective parenting and healthier family dynamics.29

CONCLUSION

Online parenting education can be an effective tool to help parents improve their parenting skills at their own pace while managing their children with ASD. The component of the program that entails positive parenting would promote the nurturing, empowerment, and growth of parents, as it would indirectly promote the child’s development and growth, which helps parents be less stressful and anxious when dealing with their special needs child.

Alternative

Further research needs to be done, especially in countries where travel and logistical issues might be a challenge for the deployment of such interventions to well-needed parents in trying to find the best possible way to manage their children by adding these parenting skills to grow as parents. It will not only reduce the cost of logistical arrangements and traveling to venues to attend such training but also the cost of obtaining therapy and support for themselves and their children.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.