INTRODUCTION

Most autistic individuals live with neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impairment in communication skills, and stereotypical behavior troubles.1 When symptoms are severe, it is highly difficult, if not impossible, for them to communicate correctly and interact with other persons around. Therefore, understanding the autistic health problems, beyond their own neurodevelopment disorders becomes a big challenge under 1st of parent responsibility. When an individual presenting autism-spectrum disorders (ASD) is unable to describe clearly his trouble, his parents try to understand what is happening and find out solutions to resolve the problems at short and long-terms. When the trouble or crisis becomes repetitive, the parents are expected to establish a “to do list”-based procedure, including verbally or writing answers to a questionnaire, medicine intakes, and other helpful tools to face the situation for a short laps time before calling a doctor.

Moreover, it is not often easy to distinguish a crisis due to the own autism disorders, such as serious disturbance and stereotypical behaviors and tantrums, to that caused by normal troubles that may occur in any individuals. ASDs are mainly characterized by deep psychological, gastro intestinal, and metabolic symptoms.2 Incomplete digestion of gluten and casein,3,4,5 leaky gut syndrome,6,7,8 hypochlorhydria of the gastric juice or low gastric acid secretion9 are among autism specific causes. Common diseases may arise from external infections and environmental pollution, which can also provoke digestive and neurological troubles with similar gastrointestinal symptoms. Therefore, routine remedies such as neuroleptic drugs for treating the own autistic crisis, previously regarded as a central nervous system (CNS) disease, should not be systematically used.

There has been a lot of literature reporting various factors responsible of ASD10,11 and their therapeutic treatments such as nutritional, diet, dietary supplements12 and other medicinal approaches.13,14 However, there has been little or no information reporting the common or uncommon additional troubles in autistic individuals and approaches for diagnosing and solving such problems.

In the present paper, we are reporting the case of a 19-year-old adult, diagnosed as autistic at the age of 3, and is suffering with poor communication skills and stereotypical behaviors. He had digestive troubles with presenting symptoms such as frequent burping, and generating repetitive crises with uncommon crying and arm agitation. After a thorough check up at several general practitioners and specialists such as gastroenterologist, neurologist, lung specialist and dentist, clinical diagnosis revealed hiatal hernia and an ulcer in the stomach upstream. Since the patient was overweight, the gastroenterologist prescribed a diet plan combined with a proton pomp inhibitor (PPI), 6-month before the beginning of the nutrition based therapy. After the 1st diet plan within 6-months, a sharp improvement was not really observed. The digestion trouble was persistent, and frequent burping was not reduced. Therefore, a second diet plan strictly nutrition-based therapy was attempted. During the 2 successive diet plans, all observations were daily recorded, and body data were weekly home-monitored. The success of such approaches was shown by the diminution of the crisis frequency, BMI drop to normal values (20-25), body mass stability as well as hiatal hernia disappearance.

METHODOLOGY

Patient

The patient was an adult man with autistic spectra with the following main data recorded in January 2015: 19 years old, 1.74 m height, BMI around 29.8. Starting June 2015, the patient was diagnosed with several pathologies such as, digestive illness, including hiatal hernia, stomach ulcer, and also vitamin-D deficiency.

Dietary Approaches

Diet plans were subdivided into 2 parts. The 1st phase was applied for a 6-month period. It was a combination of dietary therapy (diet and supplementation) with pharmacotherapy (PPI and antacids) in order to heal frequent burping, hiatal hernia, and ulcer. Generally, meals consumed were enriched with fruits and vegetables, and widely diversified with protein, fat and carbohydrate sources. The diet was also based on low-sugar and low-fat meals. Fried and high-fat foods, soda and chocolates, as well as foods known to induce acid reflux such as tomatoes and citrus were avoided.

The 2nd phase starting from the 2nd half-year was constituted by gluten and egg free-based foods, combined with a defined diet protocol, carefully applied after a metabolic typing assessment by survey analysis (Metabolic Healing Company, USA).

Recording Data Elaboration

All data such as meals, diet, snacks, supplements, medicines as well as activities were daily recorded in a database created with Microsoft excel. Any other observations noticed during the study period were also recorded in the excel sheet.

Body Data Measurements

All the data, including the body mass (kg), fat, fluid (water) and muscle proportions (%), bone mass (kg), as well as the daily energy requirement (Kcal) were measured monthly using glass body analysis scale (PW 5644 FA, AEG, Germany). The principle of the device consists in measuring the electric impedance within the human body. The device records a pulse electric signal through the body via feet contact, and then measures 6 body data, namely total mass, fat percentage, water percentage as well as bone and muscle masses. The method is based on the bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) by using appropriate population, age or pathology-specific BIA equations and established procedures.15 The BMI, which corresponds to the personʼs mass in kilograms divided by the square of their height in meter, is automatically calculated and listed with the body data. All measurements were consistently recorded at the same time, just after waking up and with an empty stomach.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Diet Plans

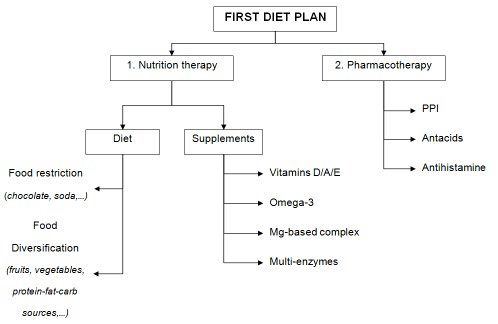

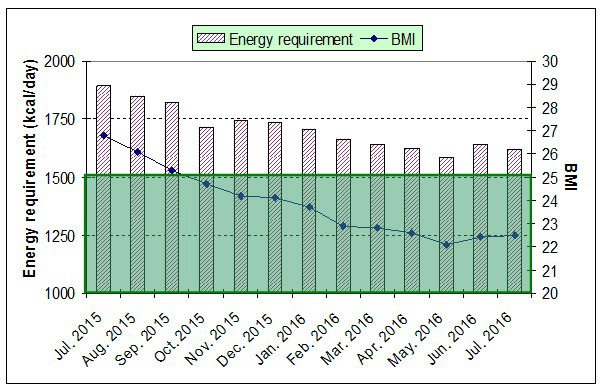

First diet plan: The first diet period includes dietary therapy and supplements in combination with pharmacotherapy (Figure 1). The dietary therapy is based on both restriction in some food categories and diversification in main nutriment sources. Diet restrictions concern all well-known foods that induce acid reflux such as, fried and high-fat foods, soda, chocolate, coffee, tomatoes and citrus fruits. Nutriment sources target certain fruit and vegetable-enriched meals, associated with protein, fat, and carbohydrate categories with high diversity, including grains, meat, dairy products, fish, and snacks in different proportions. Food supplements are constituted by vitamins D/A/E and omega-3 in pure or/and formulated oil forms, as well as magnesium and multi-enzyme complex. The pharmacotherapy includes mainly treatments with a proton pump inhibitor (pantaprazole), antacids (sodium alginate, magaldratum, etc.), and an antihistamine.

Figure 1: General scheme of the first half-year diet plan.

Such a therapy combination using diet and drugs has been followed based on practitioner and gastroenterology recommendations, but also by considering the patient overweight and his deficiency in micronutrients. A database containing all daily details of meals, supplements, drugs, physical and brain activities, as well as any observed effects, recorded in a homemade form (example given in additional files), is available. Such data allow us to follow and evaluate the diet plan impact while ensuring a good traceability.

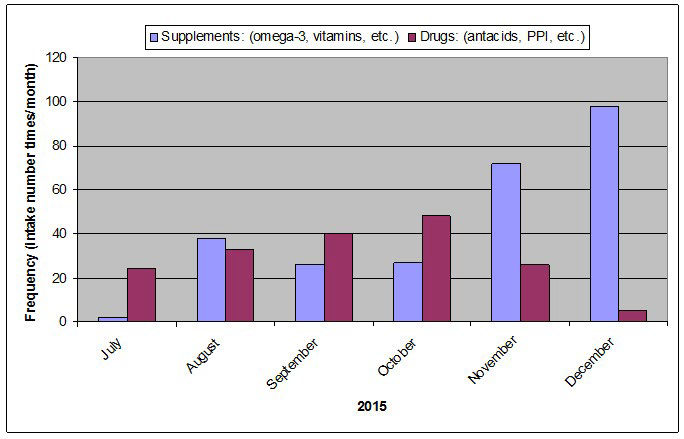

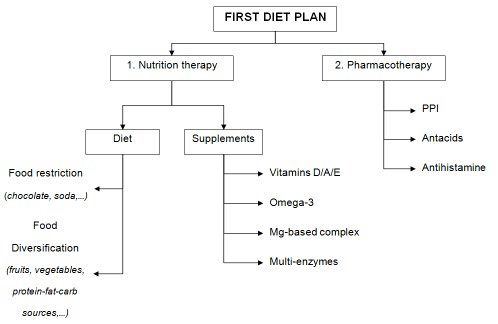

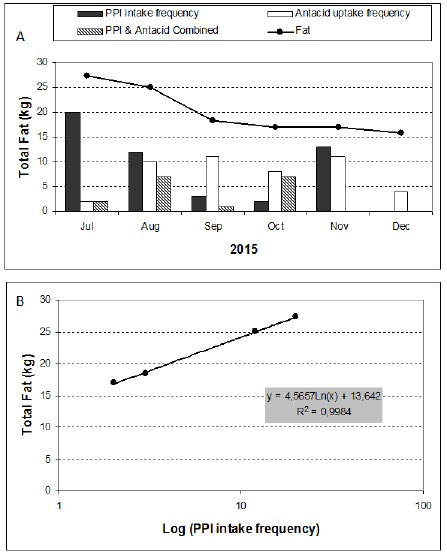

Figure 2 shows the supplement and drug intake global frequencies over this first plan phase. The diagram represents the frequency distribution or count of all supplements consumed in number times per month, compared to that of drugs over the first half-year of diet plan.

Figure 2: Global intake frequencies (sum of each category per month) of supplements (omega-3, probiotics, etc.) and drugs (antacids, PPI, etc.) for the first half-year of the diet plan (2015).

During the 1st 4 months, the drug intake frequency is slightly increased while that of supplement is quite unchanged. For the following 2 months, the drug intake is gradually reduced whereas the supplement consumption is clearly increased. Such adjustments have been attempted based on the observation of the whole therapy impact on the crisis frequency and digestive trouble persistence. The diminution of drug intake concerns mainly the PPI, which is often prescribed as the most potent inhibitors of gastric acid secretion for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. However, digestion processes involving gastric enzymes, especially in the stomach, also need certain acidity for a better digestibility. Additional supplements include mainly the intake of multi-enzyme complex in order to improve digestion, and multivitamin/amino acid/magnesium mixture for helping to maintain normal muscle and nerve function.

On the other hand, some food intolerance and allergies have been suspected. After a series of food allergy and intolerance tests, which were recommended by a nutrition expert, the patient’s intolerence to gluten and egg, but not in soya and cow’s milk proteins, has been revealed. Therefore, the 2nd diet plan strictly constituted by gluten and egg free-based foods has been started.

Second diet plan: Food and supplement categories consumed for the second phase of nutrition therapy are listed in Table 1. This second diet plan is constituted by diets and supplements without drugs. Moreover, a metabolic typing assessment has been carried out under the control of private metabolism experts. This approach aims at identifying individual metabolic requirements based on a testing questionnaire (physical, diet, psychological traits) established since 38 years of research and development by William L. Wolcott.16 It also considers the input of thousands of practitioners and hundreds of thousands of users world-wide. After the metabolic typing identification as balanced and mixed oxidizer dominance, a diet plan targeting the utilization of optimal foods for reaching recommended nutrition ratios 45% carbohydrate, 35% protein, and 20% fat was started. In theory, the balanced and mixed oxidizer dominance metabolism reaction type in the patient corresponds to the combination of 2 homeostatic system regulations, named autonomic nervous system (ANS) and oxidative system (OS). The ANS is in relation to the speeding (sympathetic) and slowing (parasympathetic) heart rates. Thus, the term balanced dominant is used for people whose organs and glands are balanced between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. The OS corresponds to the conversion rate of nutrients to energy within body’s cells, and influences in particular dietary requirements. Therefore, a nutrition plan combining various food categories as listed in Table 1 has been followed while observing the digestion trouble evolution and any improvement. The goal was to make adjustments for reaching the best diets tailored to the patient.

Table 1: Food categories and supplements for the second semester of the diet plan (2016).

(1) occasionally; (2) with proteins ; * mashed, steamed or fried; ** raw or cooked.

|

GLUTEN and EGG FREE-BASED FOODS

|

|

Breakfast

|

Snacks (1) |

Lunch |

Snacks |

Dinner

|

Supplements

|

|

1. Dairy or vegetable milk

|

Fruits, Cakes/ biscuits, or Others

|

1. Carbs & grains

|

1. Fruits Cakes/ biscuits or Others

|

1. Carbs & grains |

– |

|

Cow-goat milk

|

|

Rice/Pasta/Potatoes*

|

|

Rice, quinoa

|

|

|

Almond-rice milk

|

|

Bread/toast/crackers

|

Apple, banana, pear

|

Pancakes, bread

|

|

|

Yoghurt, kefir

|

|

Pizza

|

Smoothie

|

Potatoes*

|

|

|

Cheese

|

|

Quinoa, corn

|

|

|

|

|

2. Carbs & grains

|

|

Burger

|

|

2. Meat & fish

|

|

|

Flakes (Rice, corn)

|

Banana

|

Spring rolls

|

Biscuit, waffles

|

Beef, pork, lamb

|

Vitamins & minerals

|

|

Bread

|

Apple

|

|

Pie

|

Fish, salmon

|

Vitamins D3, K,

|

|

Pancakes

|

Youghurt

|

2. Meat/fish/Cheese

|

Cookies, brownies

|

Hamburger

|

Mg,…

|

|

Toast

|

|

Duck

|

Muffins

|

Chicken

|

|

|

Oat meal

|

|

Sardines/Tuna/Salmon

|

|

Sausage, liver paté

|

Probiotics

|

|

Quinoa

|

|

Ham, sausage

|

|

|

|

|

Cake

|

|

Chicken-Turkey fillet

|

Chips, bread/toast

|

3. Vegetables**

|

Antioxidants

|

|

3. Fruits

|

|

Mozzarella/Emmental

|

Yoghurt, milkshake (2)

|

Carrot, lettuce, cucumber

|

Coenzyme Q10,…

|

|

Banana

|

|

Lamb, liver paté

|

Energy bars

|

Cauliflower/Sprouts/Brocoli

|

|

|

Pear

|

|

Lentil balls

|

Cashews, macadamia nuts

|

Eggplant, fennel, zucchini

|

Omega-3

|

|

Apple sauce

|

|

|

Cream, cheese

|

Peas, green beans

|

Liver oil,

|

|

Pineapple

|

|

3. Vegetables **

|

Carrot/celery sticks/tahini sauce

|

Vegetable soup

|

Linseed, …

|

|

|

|

Carrot, lettuce, cucumber

|

|

Mushrooms

|

|

|

4. Meat

|

|

Avocado

|

2. Beverage

|

|

Phytochemicals

|

|

Chicken fillet

|

|

Fennel

|

Chamomile-ginger tea |

4. Fruits

|

Laetiporus,

|

|

Beef

|

|

Pea soup

|

Rice milk

|

Banana

|

Lapacho,

|

|

AND/OR

|

|

Spinach, kale, cauliflower

|

Water, ice tea

|

Strawberry

|

Tisanes,…

|

|

5. Others

|

|

4. Fruits

|

Fruit juice bio

|

Mango

|

Others

|

|

Carob, carrot juice

|

|

Mango, pear, apple

|

|

Pear, pineapple

|

Antihistamine,

|

|

Chicory, cashew, chamomile

|

|

Pineapple

|

|

|

Enzymes,

|

|

|

OR

|

|

OR

|

|

|

Proteins, butter

|

|

5. Others

|

|

5. Others

|

|

|

Honey, jam

|

|

Yoghurt, cream, cake

|

|

Waffle, cake, Yogurt

|

…

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pie, Ghee

|

|

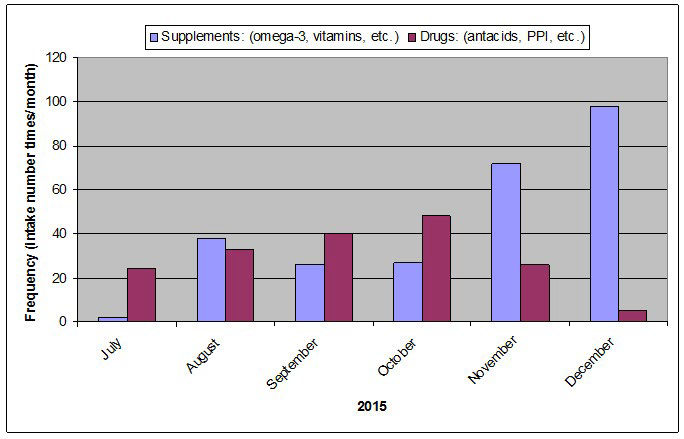

BODY MASS DATA

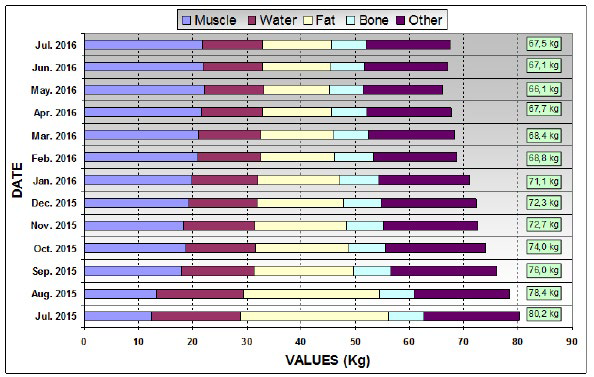

Figure 3 shows the body data changes over one year under 2 diet plans. Body-mass data were monthly measured to monitor the effect of the whole nutrition therapeutic approach, including 2 successive diet plans. Body data correspond to body mass, fat, fluid (water) and muscle proportions and bone mass, as well as the daily energy requirement (Kcal). The latter corresponds to the amount of energy that the body requires per day during complete rest, that is, while sleeping where the body temperature is almost unchanged, and on an empty stomach. All data obtained with the home-model impendence meter (PW5644FA, AEG) for this investigation were comparable with those measured at the general practitioner using a professional device BIOZM2. Only a difference around 1% was observed, for instance, with the body fluid data. As indicator, standard errors between the results obtained with home-model and professional devices were around 1% with the body water percentage and less than 5% for the body-fat percentage. It is to be noticed that, except the body mass in absolute value, the other body data monitored during our investigation were analyzed in terms of relative data changes over one year.

Figure 3: Evolution of body data over one year of 2 diet programs (2015-2016); Total body mass in kg on the right of the histogram.

It appears that: (1) the body-mass decreases from 80.2 kg to 72.3 kg during the 1st half-year, before reaching a stable value around 67 kg after the second diet plan; (2) the body fat follows the same trend with a sharp decrease for the first diet plan, and remains constant after 9 months of nutrition therapy; (3) there is a gain in the cumulated body water and muscle mass; and (4) the bone mass was unchanged over one year, indicating trends toward good health features.

The decrease of the body mass and fat with the increase of muscle mass during the first 4 months of nutrition-based therapy is naturally correlated to a diet containing all recommended foods characterized by fruit and vegetable-enriched and varied foods, but also with restricting diet without soda, chocolates, onions, etc. It may be due to the combination of different effective dietary strategies for reducing mass such as lower fat, higher protein, and lower glycaemic index diets.17 The fact that the body fat decreases while the muscle mass increases is coherent to the effective diet strategy for mass loss.

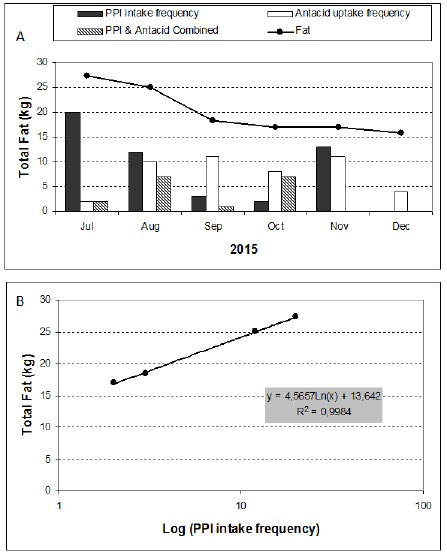

However, the diminution of body fat compared to that of the PPI intake frequency is striking as shown in Figure 4. Both indicators decrease in similar proportions over the 4 months of the 1st diet plan. By searching in the literature, it has been reported that omeprazole and other PPIs delay gastric emptying,18,19 which induces postprandial fullness, dyspeptic symptoms, gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth, and subsequent mass loss.20 On the contrary, long-term treatment of PPI is rather associated in general trend with mass gain in patients with gastro-oesophagus reflux disease.21

Subsequently, the PPI intake was stopped in the beginning of the 2nd half-year after which the eructation symptoms were diminished.

Figure 4: Some attempts of data correlations between drug intake frequency and fat mass loss

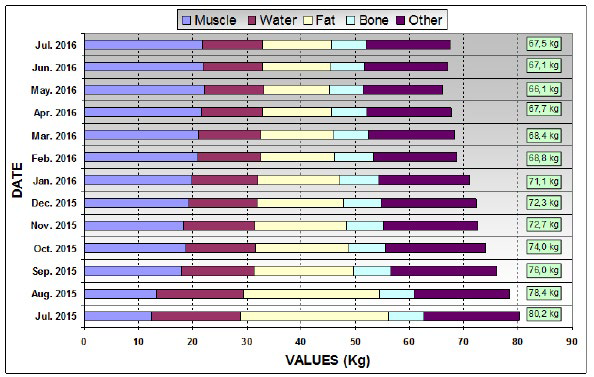

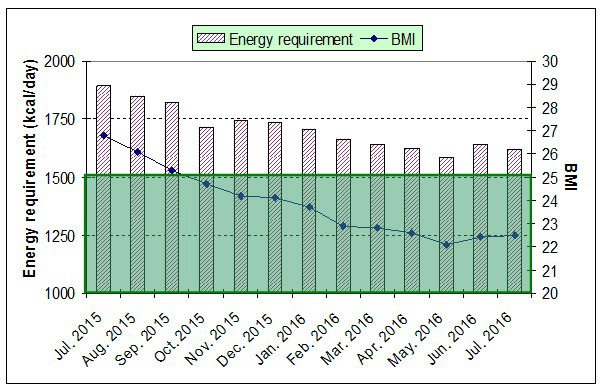

Figure 5 shows the changes in the BMI and energy requirement over one year under the 2 diet programs. The BMI value reaches the normal zone (20-25) after 3 months of the first diet plan while continuing to decrease down to 22.5. This value remains practically unchanged after 7-8 months of nutrition therapy. The energy requirement follows the same trait for reaching also a constant value close to 1700 kcal.

Figure 5: BMI and energy requirement evolutions over one year under 2 diet programs.

It appears that both BMI and body data for the patient age and height stabilized at normal values after 6-months of nutrition-based home-made therapeutic approaches. Also, according to the baryta-based radiography examination of oesophagusstomach-duodenum, hiatal hernia disappeared after one year of nutrition therapy. The frequency of crisis is also reduced from 5 per month in the first half-year to 3 during the second half-year with sometimes one crisis per month. Such a success may be simply explained by reaching the so-called “optimum nutritional balance” with selected foods and diet for the patient. If the first diet plan enables his weight loss for reaching a normal BMI by specific restriction and diversification in foods, the second one rather allows his BMI to be stable by optimizing his nutrition, thanks to the metabolic type results. In addition, the elimination of gluten and eggs from the second diet plan certainly contributes to the improvement of his digestive health by avoiding allergies and food intolerance.

CONCLUSION

This investigation shows the success of nutrition-based therapeutic approaches for solving autistic digestive troubles. Two successive diet plans allow us to treat the patient overweight, reaching after four months a normal BMI value that remains stable over one year. The general health of the patient is improved as his crisis frequency is reduced, and the related digestive disorders especially shown by the presence of hiatal hernia, and ulcer are solved. Such a communicating-limited patient management is a real challenge, but also very enriching experiences for his family surroundings, as well as sustainable by the database establishment after recording all information throughout the diet plans. An obvious perspective would be to process such data by computational routes to access in easier and faster manners any request information for similar or other cases. In purely scientific and medical viewpoints, our approach will restart the debate on the mechanism of gastric acid secretion inhibitors (proton pump inhibitor) on the fat mass loss, which would be favorable for fighting overweight and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. B. Rassart and Dr. R. Nassar for the diagnostics of egg and gluten intolerances, and vitamin-D deficiency, respectively and Dr. V. Sethakr of Clinique SaintElisabeth for the diagnostic of hiatal hernia. Their acknowledgment also goes to Julie S. Donaldson for providing the metabolic typing data, and the Radiology Center of Clinique Saint-Pierre for the Esophagus Stomach Duodenum (ESD) radiography. Finally, their thanks go to all those who assisted for the present investigation in one way or another.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

– HR (PhD) conceived and designed the investigation, and contributed in writing the manuscript and data processing (>90%), and home-recording and monitoring details and body mass data (20%);

– HR (MS) contributed in writing and data processing (<5%), literature searching (><50%), food preparation (100%), and home-recording and monitoring details and body mass data (80%);><5%), literature searching (<50%), food preparation (100%), and home-recording and monitoring details and body mass data (80%);

– AR (MS candidate) contributed in writing (<5%), literature searching (>50%) and processing (>90%).