INTRODUCTION AND SIGNIFICANCE

The Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory (SASSI-A3) is a psychological screening measure designed to screen people who are 13 to 18-years of age for substance use disorders. The first version of the Adolescent SASSI was designed to identify chemically dependent adolescents; it was published in 1990. The second version, SASSI-A2, was published in 2001 with additional scales and improved accuracy and has been used in many diverse types of service programs, including addictions and other types of adolescent treatment programs, as well as correctional settings.1 The research conducted to develop the original Adolescent SASSI is reported in the Adolescent SASSI Manual and for the second version in the SASSI-A2 Manual.2,3 Substance use disorder has continued to affect people of all ethnic, cultural groups and ages, and in recent years to a greater degree, adolescents.4 In 2005 nearly 50,000 adolescents (12-17-years-old) presented to hospital emergency departments because of the non-medical use of prescription painkillers. Since that time, however, emergency room incidents for non-medical use of prescription narcotic pain relievers have continually increased in people under age 21.4 Over 100,000 people, many of which were teens, died of drug overdoses in the United States during the 12-month period ending April 2021, according to provisional data published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5

The ongoing program of research at the SASSI Institute, in tandem with the expressed needs of counselors and other treatment providers, prompted the development of a research version of the Adolescent SASSI-A2 that was used to develop the SASSI-A3.6 The research version included all the previous items on the Adolescent SASSI-A2, along with the addition of new items and updated language reflecting current teen drug-use trends.7 This article focuses primarily on the defensiveness scale (DEF scale) and validity check (VAL Scale) out of the twelve total scales on the adolescent instrument as available today. These two scales are particularly important as recent research with adolescents shows decreases in openness as regards to age and novel information regarding the timing of the association between substance use and personality.8 The DEF scale independently, and when considered in combination with other scales on the SASSI-A3, can provide valuable insight into teens’ behaviors.9 These Scales are described more in depth later in this manuscript. Additionally, the friends and family risk scale (FRISK scale), when elevated, can indicate that the teen may have trouble recognizing and be in denial about, and unable to accept, the consequences of their substance misuse. Further research and findings of other scales on the SASSI-A3 and their utility is available elsewhere.7,10,11

METHODS

Sampling Procedures

For this study, we review treatment mandated teens’ SASSI-3 results. We discuss how their responses demonstrate defensiveness and denial, possibly brought on by the treatment mandate experience. Please contact The SASSI Institute for reprints of articles that present additional procedural and more elaborate methodological discussions on the development and validation of the adolescent SASSI-A3 substance use disorder screening inventory.

Human Rights Protections and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Adherence

This study entailed minimal risk to participants, in that study participation consisted of providing anonymous responses on a screening survey regarding alcohol and drug-related experiences and attitudes. The risk of harm is thus no greater than would be encountered in standard psychological testing. In addition, treatment participants were invited to participate in the study by assessment professionals who use the SASSI screening survey in their practices, and who have an established professional relationship with the respondent. Both parents and teens decided whether to provide permission and assent to study participation.6 Participants were allowed the option of skipping any question/s or withdrawing from study participation at any time without incurring any penalty or rescinding any rights to which they would otherwise be entitled.

Participants

The data set from adolescents in treatment consisted of 164 cases from teens aged 13-18. All clinicians were qualified SASSI users who administered the SASSI-A3 via the SASSI Institute web-based screening application at www.sassionline.com. In appreciation for the use of their anonymous responses, The SASSI Institute made a $5 donation to the teen’s choice of a youth or pet charity.

Data Collection Procedures for Teens

As described in greater detail elsewhere, The SASSI Institute’s ongoing Online Security Commitment ensures our systems and processes meet or exceed all state and federal regulations, including Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), 42 code of federal regulations (42 CFR), FamilyEducationalRightsandPrivacyAct (FERPA), and other regulations regarding confidential client data.6 To protect the privacy of study participants and confidentiality of the study data, each administration of the screening survey was automatically assigned a SASSIonline platform-generated sequence of characters to readily and singularly identify each case for the duration of the study. No identifying fields were formatted for the research administrations that would allow counselors to enter participants’ names, date of birth, or any other item of personally identifiable information about the participant. Each participating counselor created a master list to match the participant’s study identification (ID) number to the participant’s name so that the counselor knew the associated identity for each screening report. The master lists were not shared with the study investigators. In addition, participant responses on the screening survey consisted of true/false, categorical, and numerical responses, which were numerically coded. At all times, counselors retained the ability to opt out of providing a diagnostic evaluation for a case, and instead choose to use the SASSIonline platform for paid administrations of the screening questionnaire. A separate research module on the SASSIOnline platform allowed participating counselors to administer the research survey to participants. We encrypted all data transmissions and de-identified client information so that all identifiable client information was maintained as encrypted data.6 All research protocols and procedures were reviewed by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to study commencement.

Measures

SASSI-A3: Research version: Participants completed the research version of the SASSI-A3 which consisted of 87 true-false items and 24 face-valid alcohol and other drug frequency items that measure how often (0=never, to 3=repeatedly) respondents have engaged in and experienced effects from the use of alcohol and other drugs within a specified time frame. There are two possible outcomes: “high probability” or “low probability” of SUD.7 As mentioned earlier, we focused primarily on the teens scores on the DEF and VAL scales on the SASSI-A3.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5)

Clinicians’ diagnoses regarding the presence or absence of substance use disorders were obtained in accordance with the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 symptom criteria.12 Counselors also specified the class of drug(s) the substance use disorder was related to for each diagnostic evaluation they conducted.

Data Analysis and Results

Our total sample pool consisted of 164 teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 (mean=16-years-old). Sixty-seven percent (67%) were Male, 33% Female. Adolescents in the overall sample identified themselves as White (49%), Black/African American (25%), Hispanic (15%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (1%), Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (1%), Multiracial/Other (9%). One percent reported being employed full-time, not employed (87%), part-time (11%), volunteer (1%). Forty-eight percent (48%) reported living with their parents, living with other relatives (7%), living with friends/other (10%), in a group home (3%), or in residential treatment (32%).

The mandated treatment sample consisted of teens referred from the following types of programs for further assessment and possible treatment. Thirty-four percent (34%) were criminal justice system referrals, social service programs (12%), medical professionals (2%), and other/unknown (52%). They were referred out to the following settings: criminal justice programs (2%), social services (12%), substance use treatment (82%), and other/unknown (4%). Thirty-seven percent (37%) of the teens had received previous SUD treatment and the mean number of arrest records for the group was two arrests.

We looked at clients’ screening results on the SASSI-A3 in the mandated treatment group. The SASSI-A3 screening results, as shown in Table 1, are reasonably robust among the mandated clients. One hundred and twenty-one (121) of the 164 teens in our sample tested high probability of having an SUD and three had elevated, clinically significant, DEF scores. The mean age of the 121 who tested high probability was 16-years of age. Sixty-nine percent (69%) were Male, 31% Female and they identified themselves as White (45%), Black/African American (26%), Hispanic (16%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (1%), Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (2%), Multiracial/Other (10%). Of the 43 that tested low probability, 26 had elevated DEF and/or VAL scores alerting their clinician that they were not likely to have been forthcoming when answering the questionnaire, recommending further evaluation. The mean age of the 26 with elevated DEF and/or VAL scores was 16-years of age. Fifty-four percent (54%) were Male, 46% Female and they identified themselves as White (62%), Black/African American (15%), Hispanic (19%), Multiracial/Other (4%). Fifty-nine percent (59%) of the referrals among those who tested low probability, but had elevated DEF and/or VAL scores came from sources outside of the justice system, social service programs, and/or medical professionals. Prior research conducted on the SASSI-A3 included a thorough logistic regression analysis using type of assessment setting, together with all client demographic variables as predictors of screening accuracy; these analyses showed no significant effect on accuracy.6 It is noteworthy that additional larger sample size research on the SASSI-A3 demonstrates that the inclusion of subtle items (questions not directly related to substance use), and the research on defensive responding enable SASSI-A3 classifications to be quite accurate, even when DEF scores are elevated.7

| Table 1. Screening Outcomes |

| SASSI-A3 Screening Outcome |

| Sample Group |

High

Probability SUD |

Low

Probability SUD |

Total |

| Mandated treatment |

121 |

43 |

164 |

| Note. Sensitivity for the mandated sample=91.1%. Number of participants presented in the table. |

DISCUSSION

This study’s objective was to demonstrate the value of identifying high-levels of defensiveness and possible denial of usage in teens mandated to treatment by using the SASSI-A3 and breaking through defensiveness and denial to move forward in the treatment process. The SASSI-A3 was designed to identify individuals in need of further evaluation for SUD, including individuals who may be unable or unwilling to acknowledge their substance misuse. Questions directly related to substance use (face-valid) and questions not directly appearing to be about substance use (subtle items) are organized into nine scales that are utilized in a series of decision rules to produce a dichotomous SUD screening classification. There are two possible outcomes: “high probability” or “low probability” of SUD.7 The SASSI-A3 contains a Defensiveness scale score (DEF) which identifies defensive responding and lack of forthright disclosure not necessarily related to substance use. Another scale is the Validity Check (VAL) which identifies some individuals for whom further evaluation may be of value, even though they are classified as having a low probability of an SUD. When a client is identified as low probability on the SASSI-A3 screening outcome, and they have an elevated score on the DEF (10+) and/or VAL (5+) scale this can alert clinicians that the teen is likely not being forthcoming and further evaluation is recommended (see brief case example 1 below). These two scales were designed to provide practitioners a way of identifying clients who were likely minimizing disclosure of substance use. This is particularly true when screening results are not consistent with collateral information within the case file regarding a client’s likely abuse of substances, as demonstrated elsewhere.11 Because the SASSI-A3 is highly resistant to faking good, when teens whose screening outcome on the SASSI-A3 results in a high probability, but they have a high DEF score this can provide additional insight into the client, providing further insight and benefitting the clinician in helping the teen to acknowledge existing problems and begin to make positive changes (see brief case example 2).11

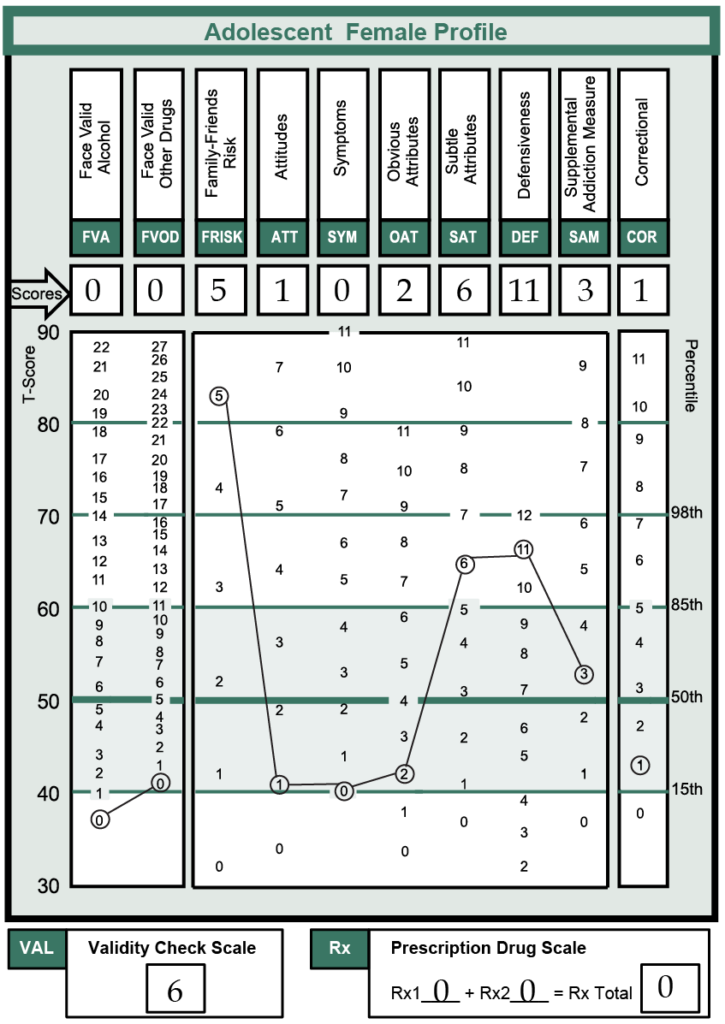

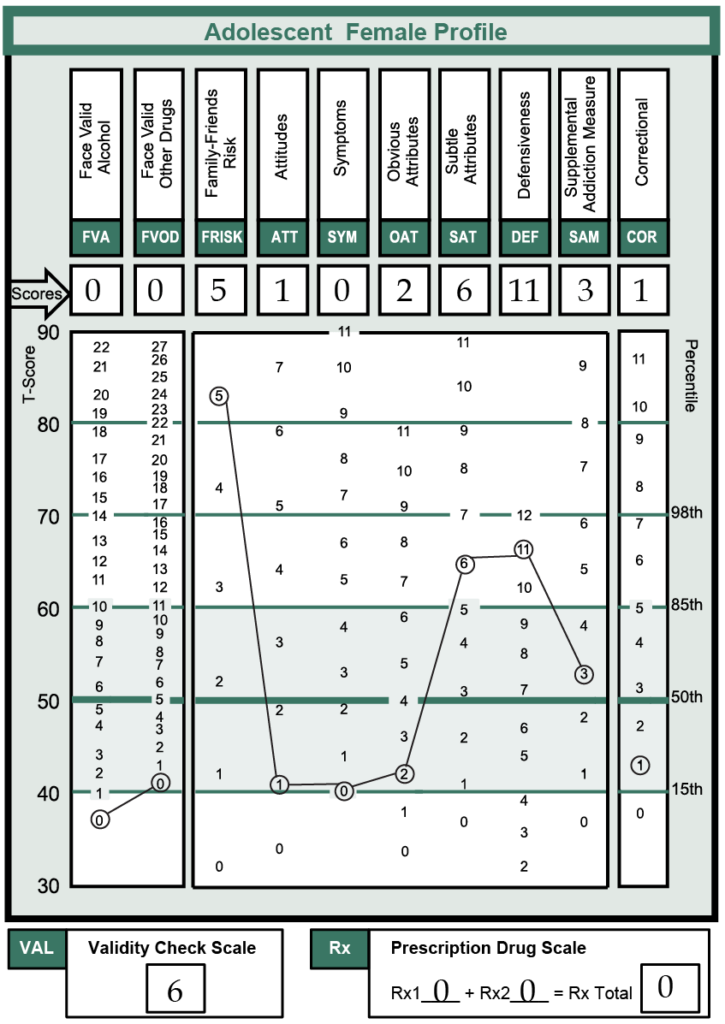

Below we present a couple of brief screening examples of randomly selected cases from mandated clients given the SASSI-A3. Both teens have elevated DEF scores, but one screened high probability for an SUD and the other screened low probability. The SASSI-A3 has additional scales beyond the DEF scale discussed in this study. Scale scores on the SASSI-A3 can provide clinically useful information when above the 85th percentile or below the 15th percentile (this is the same as T-Scores above 60 and below 40) on the profile sheet (Figures 1 and 2).7 Recognizing these profile patterns has proven valuable in directing the ongoing course of assessment and treatment planning. Inferences drawn from SASSI-A3 scale score interpretation are hypotheses to explore based on years of feedback from professionals using the instrument.7 For in-depth information on interpreting SASSI-A3 scale score results, please refer to the SASSI-A3 User Guide & Manual.7

NAOMI’s BRIEF CASE SCREENING EXAMPLE

For this case study, we examine the SASSI-A3 screening results of a 16-year-old female whom we will call “Naomi” as shown below in Figure 1. Even though Naomi did not acknowledge any substance misuse on the face-valid alcohol or face-valid other drug scales (FVA=0 and FVOD=0) which are scales that measure how often respondents have engaged in and experienced effects from the use of alcohol and other drugs within a specified time frame (e.g., lifetime, past 12-months) (for example: Gotten into trouble at home, school, work or with the police because of your drinking?; Used alcohol and medications or drugs at the same time?) as well as a zero on the symptoms (SYM) scale, which measures the extent to which the client acknowledges the problems and consequences of their substance use history and contains face valid items (i.e., True or False: I have sometimes drunk too much beer or other alcoholic drink) she still tested positive “High Probability” on the SASSI-A3 based on the subtle scale scores. Naomi has a lack of acknowledgment of her problematic behavior that extends beyond substance misuse. Her elevated DEF score (11), which is above the 85th percentile, indicates she was highly defensive while completing the questionnaire. One inference that may be drawn is that she is likely to have difficulty disclosing information about her usage. On the friends and family risk (FRISK=5) questions, a scale derived from face valid items that measures the extent to which the client is part of a family/social system that is likely to enable substance misuse. (i.e., True or False: One of my parents was/is a heavy drinker or drug user), she endorses items regarding her parents’ substance misuse, their negative moods and her sense of distance from them. Her low score on the Obvious Attributes (OAT=2) scale, a scale that provides information regarding the extent to which the client is aware of, and able and willing to acknowledge some behavioral characteristics that may accompany substance misuse and indicates that she is likely to have a hard time acknowledging her “character flaws”. Finally, her Subtle Attributes (SAT=6) score, a scale that indicates denial or lack of insight on the impact substances have in someone’s life, is elevated which may provide her with a basis for focusing exclusively on her parents’ problems, while avoiding recognizing her own role in the problems and negative feelings she may be having.

Figure 1. Naomi’s SASSI-A3 Profile Scafe Scores *Study Participant’s Name Changed for Confidentiallity Purposes

Treating Naomi is likely going to be challenging. Her SASSI-A3 results suggest that she has a substance use disorder and has a tendency to focus on others, thereby not assuming responsibility for making positive changes in her own life. It will be important to support her in a process of gaining increased awareness of her role in both causing, and alleviating problems in her life.

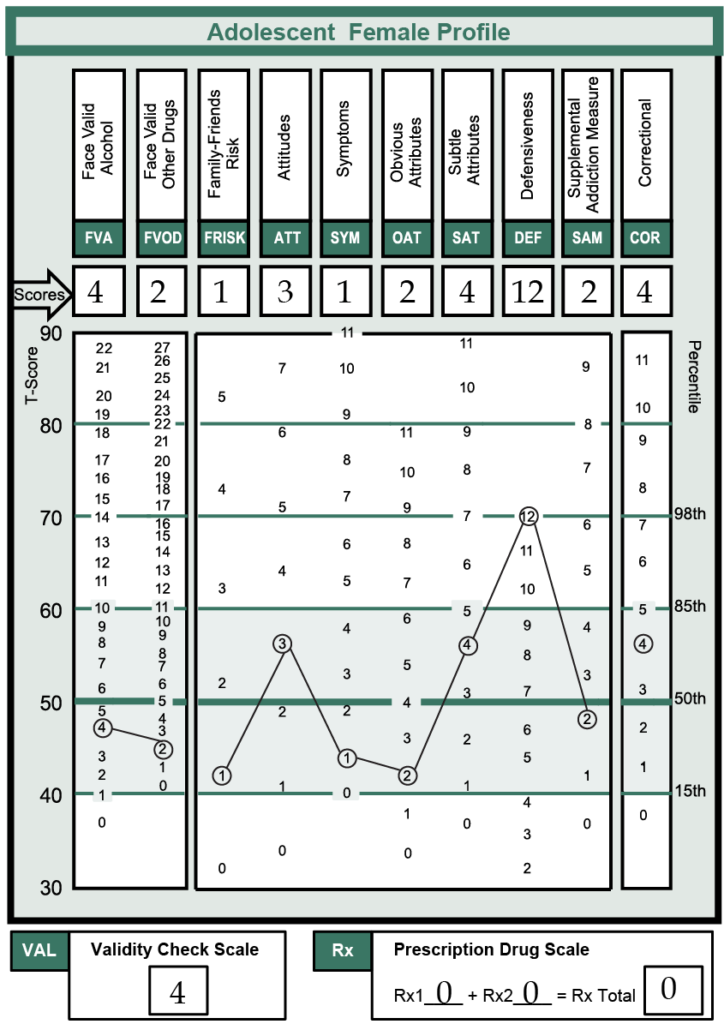

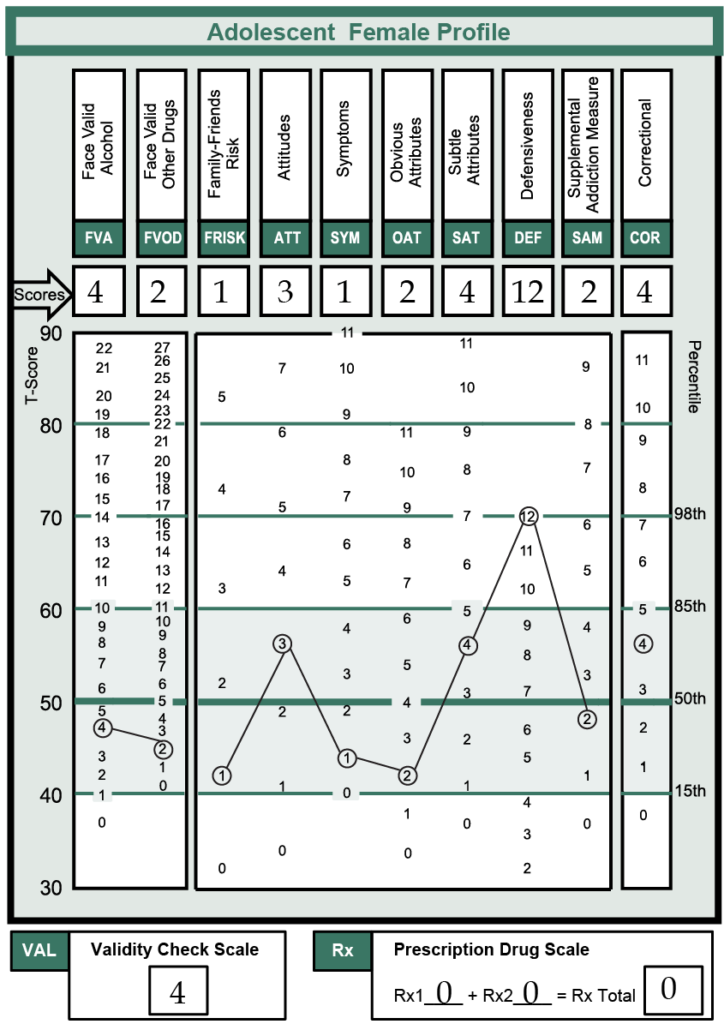

MELODY’S BRIEF CASE SCREENING EXAMPLE

For this case example, we examine the SASSI-A3 screening results of a 17-year-old female whom we will call “Melody” as shown below in Figure 2. Melody was classified as low probability of having a substance use disorder. DEF is the only scale that is elevated above the 85th percentile, which makes it clinically significant.

Figure 2. Melody’s SASSI-A3 Profile Scale Scores *Study participant’s Name Changed for Confidentiallity Purposes

Melody’s score on the DEF scale indicates she responded on the SASSI-A3 in a manner that is similar to adolescents who were instructed to answer in a way that conceals evidence of substance misuse. Therefore, we might infer that Melody responded in a defensive manner. An elevated DEF on the SASSI-A3 does not, however, necessarily mean that the adolescent is defensive in regard to substance misuse. Nor does an elevated DEF tell us whether the defensiveness is in response to the events surrounding the assessment, or if it is part of a more general personality trait. She should be flagged for possible further evaluation, especially if her behavior and history indicate that there is a basis for concern. It may be of value to continue to monitor her for substance misuse.

Limitations and Future Research

It is important to realize that the SASSI questionnaire is an objective screening tool. As such, it cannot be claimed that it can be used as a standalone assessment instrument. In fact, our literature, website and social blogs state this fact explicitly. Despite this, professionals worldwide have used SASSI tools as part of overall assessment packages for over three decades.

This paper focused primarily on the importance of identifying Defensiveness and denial in mandated clients, but clinical experience with the SASSI has produced subjective clinical observations of correspondence between other scale scores. In the future, we will be conducting further research verifying the utility of other scales on the SASSI-A3 instrument to provide a fuller understanding of their use, interpretation, and value when used properly within multiple treatment settings among adolescents.

The data used for this study was comprised of a convenience sample we intentionally extracted from the larger validation study, and solely for the intent of illustrating defensiveness among mandated teens. Data used to validate the screening instrument were submitted by practitioners engaged in ongoing programs of substance use assessments and screening with teens.6,13 Pursuant to IRB regulations and mandates, incarcerated teens, or those in Foster Care were not included in this study. Future research including these settings would extend the generalizability of current findings to these populations, particularly as it pertains to defensiveness. Additionally, future research should include a qualitative piece including focus groups.

CONCLUSION

Working with teens can be extremely difficult given their rapid mood changes, intensely felt experiences and shifting states of compliance, openness and defiance. This is especially true when working with teens who did not enter treatment willingly. This fact further complicates the difficult task of distinguishing between a teen acting out and being defensive because of their substance use, or just being a defiant teen dealing with adolescence. When teens are mandated for treatment, they may often feel their choices have been taken away and the counselor may be viewed as more of a power authority rather than a concerned and helping figure. The counselor should maintain awareness that the client was mandated for treatment and why they were mandated. They should also be aware of any requirements to successfully complete treatment that may have been placed on the client. As a result of these contingencies, the teens’ primary focus may be completing those requirements, rather than focusing on their underlying SUD that got them mandated for treatment in the first place. It is thus important that the counselor not only focus on the needs of the referral source, but provide empathic focus on all of the teen’s needs, facilitating their becoming an active partner in the treatment process. Proper training on the use and interpretation of the SASSI is worthwhile for professionals to make full and appropriate use of the instrument and begin breaking through client barriers towards achieving a successful outcome.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.