INTRODUCTION

Nutrition-related diseases are still increasing among children in Kuwait.1,2,3 Kuwaiti children are gradually getting engaged in further negative dietary habits.2,4 Caregivers, specifically parents, have a major influence in providing either healthy or unhealthy foods to their children – thus, playing a role in shaping their children’s health.5,6 The main factor of children’s food choices is strongly controlled by parent’s food choices.7,8,9 A healthy diet helps children to grow normally and learn, as well as help in preventing obesity and weight-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, cancer, and anemia.10,11

As more parents work away from home, their children’s eating patterns continue to deviate from being healthy by time and so does their health.12 Some working parents claim they do not have the time to prepare meals for their children on a daily basis; thus, they opt for what is ready and easy to feed them.13 Previous studies showed that children’s preference and intake patterns are largely a reflection of the foods that they have become familiar with.13 Therefore, caregivers’ consumption of food items is positively related to their availability at home. Parents may understand that fruits and vegetables provide vitamins and minerals that are essential for their children’s growth.14 Also, they may have other plant-based food items that contain nutrients that are thought to be important in reducing the risk of some diseases.11 However, such healthy dietary patterns could be overlooked by parents in the face of convenience.

The older generations of parents suffer from various health diseases, which may sometimes be traced back to food eating patterns.14 Generally, the older generations have a traditional eating pattern and are somewhat stubborn about changing their lifestyle; therefore, not much can be done to dispel their traditional lifestyle and eating habits.5,15 As demands for medications in Kuwait increase, therein lays the hope to decrease the risk of those same diseases for younger generations.3 As time changes and nutritional information are discussed openly in society, lifestyle changes such as understanding the importance of fruits and vegetables in one’s diet are also occurring. In present days, studying the grocery shopping habits of Kuwaiti parents can offer this study a window on their children’s eating patterns since their eating patterns are largely shaped by their parent’s food choices.14

The ready-to-eat meals, fast food, junk food items (e.g., candy bars, cookies, and potato chips), and sugary soft and artificially flavored drinks tend to make up the majority of the Kuwaiti child’s diet.15 Unfortunately, while these food choices and eating patterns continue to grow, diseases such as obesity and diabetes increase amongst children in Kuwait.16 Parents powerfully shape their children’s early experiences with food and eating and provide food choices for them. Children are very much ready to learn to eat the foods of their adult’s diet, and their ability to learn to accept a wide range of foods is remarkable.2,10,11 The nutritional knowledge level of parents highly influences their children’s consumption of fruits, vegetables, and other food choices – in addition to being the link to decreasing the risk of children’s health disorders.3,6,16,17

Studies on patterns of grocery shopping by Kuwaiti parents and consequences of such on their children’s nutrition are lacking. Thus, this study was of interest to assess aspects of Kuwaiti parents’ food shopping choices as influenced by demographic factors and by their level of nutritional awareness. This study will open the door for further studies of the same emphasis, which will enhance nutritional education and the realization that food plays a crucial role in a child’s life and health other than just satiation.

METHODS

Participants

A cross-sectional study was carried out among Kuwaiti parents aged between 18 to 50 years and above who grocery shop for their families. The subjects of this study were randomly selected 100 Kuwaiti parents who were grocery shopping at 6 supermarkets at different locations supermarkets were chosen in mostly Kuwaiti citizens residential areas. This was intended to enhance the chances of having Kuwaitis as subjects for this study. Two different sectors for grocery shopping were represented: the public sector which are known as co-operatives and privately-owned supermarkets.

Administered Questionnaire

Data collection was based on a questionnaire of 28 items that was designed to cover three main categories: demographics, parents’ nutritional knowledge, and children’s nutrition. Four senior nutrition students visited the 6 supermarkets. Students. grouped into two pairs, collected information from 100 parents who were grocery shopping. Random costumers of the survey’s age groups were selected and asked if they were parents then interviewed. To conduct the interview, members of the study branched off in groups of two and approached individuals or couples while they were doing their shopping. After asking for their permission to participate in the survey, the inquiry was initiated and per their consent. Naturally, there were some people who hesitated; however, most were agreeable to respond to the questions being interviewed. One interviewer asked the questions, and the other recorded the responses. Participants were interviewed during different hours of the day.

Data Management

After checking for completeness of responses, the interviewing team proceeded to the processing stage. Data of all questionnaire items were entered electronically into a Microsoft Excel document to create charts presenting the collected responses and to find out relationships between each set of data. Data were then analyzed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 16 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) to aid in tabulating and simply presenting the findings. The Chi-Square test was used to examine the association between variables at the p<0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, this study included 100 Kuwaiti parents. Most of the respondents were women (66%). The age of parents ranged from 18-45 years and above. Most of the parents (92%) were married, and (63%) of participants were college graduates. Results showed that 56 % of the participants were working parents while 44 % were not. Most of the parents (71%) were with high monthly household income of (1000-2000 KD/month). Half of the participants had 1-3 children. The children’s age ranged from 2-10 and 11-18, which were almost equal in percentage. The majority of participants (61%) shopped at co-operatives and 30% preferred shopping at privately-owned supermarkets. Most of the parents (84%) allowed their children to choose their food while grocery shopping.

| Table 1. Demographic Information of Kuwaiti Parents Who Shop for Groceries (n=100) |

|

Item

|

Description |

%

|

|

Gender

|

Male |

34

|

|

Female

|

66

|

|

Age of parent

|

18-30

|

19

|

|

31-45

|

37 |

| >45 |

44

|

|

Marital status

|

Married

|

92 |

| Divorced |

7

|

|

Widowed

|

1

|

|

Education level

|

Graduate |

63

|

|

Undergraduate

|

19 |

| High School |

18

|

|

Work status

|

Working |

56

|

|

Not working

|

44 |

| Family income (KD/mo) |

200-900 |

23

|

|

1000-2000

|

71 |

| >2000 |

6

|

|

No. of children

|

1-3 |

50

|

|

4-6

|

42 |

| >6 |

8

|

|

Age of children

|

2-10 |

53

|

|

11-28

|

47 |

| Where do you usually grocery shop? |

Private supermarket |

30

|

|

Cooperative

|

61 |

| Both |

9

|

|

Do you allow your children to choose their own food while grocery shopping?

|

Yes |

84

|

|

No

|

16

|

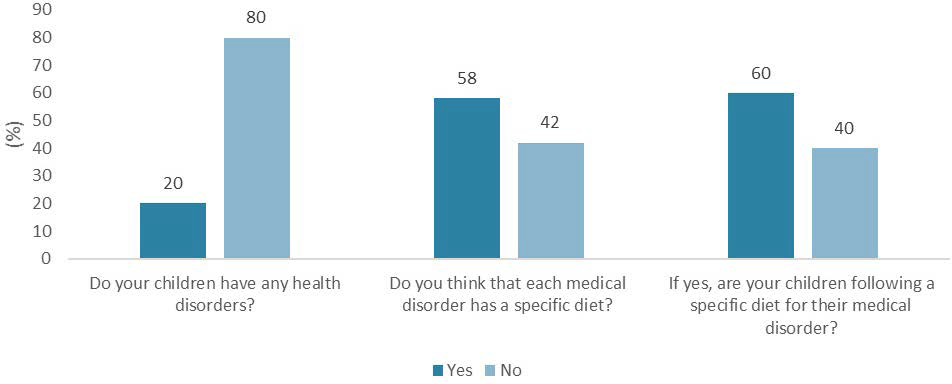

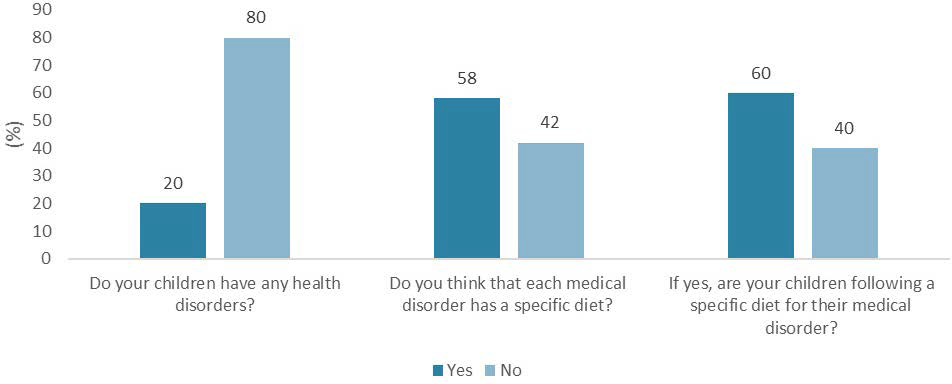

Information on child health disorders and awareness of parents about special nutrition regimens are shown in Figure 1. The results showed that 20% of the subjects had children with health disorders. More than half of the participants thought that children with health disorders require special diets; however, only 60% of the parents with health disordered children were following a special diet for their children.

Figure 1. Child Health Disorders and Parents’ Awareness toward Special Nutritional Needs

Nutrition Knowledge

Information items on nutrition knowledge of respondent parents are presented in Table 2. Media was the major source of parents’ nutrition information (54%), followed by family doctors (20%), books and magazines (20%), and friends (6%). About half of participants (51%) were familiar with the nutrition fact label, with calories being the most important factor in the label (26%). The majority of parents were shopping for nutrition claims (74%). Low fat products (60%) were the major concern for parents to seek, followed by smaller percentages of products that were natural, organic, low sugar, or cholesterol-free – respectively. More than half of the participants (54%) had enough knowledge of the food ingredient label. Most of parents (58%) were purchasing ready to eat meals. The mostly consumed food group by children was meat (60%). About 43% of the parents felt that their children were not consuming enough fruits and vegetables. The majority of parents (92%) allowed their children to consume junk foods, juices, and sugary soda drinks.

| Table 2. Parent’s Nutrition Information and Health Data |

|

Item

|

Description |

%

|

|

Source of nutrition information

|

Media |

54

|

|

Family Doctor

|

20 |

| Books and magazines |

20

|

|

Friends

|

6 |

| Are you familiar with food label? |

Yes |

51

|

|

No

|

49 |

| Most important information of the nutrition fact label |

Calories |

26

|

|

Fat

|

17 |

| Salt |

3

|

|

Sugar

|

16 |

|

All

|

5

|

| None |

33

|

|

Shopping for nutrient claims

|

Yes |

74 |

| No |

26

|

|

Knowledge of food ingredient labe

|

Yes |

54 |

| No |

46

|

|

If yes, what food label ingredient?

|

Sugar |

4 |

| Additives |

48

|

|

Allergy Components

|

6 |

| None |

42

|

|

Purchasing ready-to-eat meals

|

Yes |

58 |

| No |

42

|

|

Most eaten food groups

|

Dairy

|

11 |

| Meats |

60

|

|

Fruits

|

3 |

| Vegetables |

6

|

|

Grains

|

16 |

| All |

4

|

|

Do you allow your children to choose their own food while grocery shopping?

|

Fruits

|

20 |

| Vegetables |

32

|

|

Grains

|

5 |

| All |

43

|

|

Do you allow your children to consume these items?

|

Junk food

|

39 |

| Juices |

34

|

|

Soda drinks

|

20 |

| None |

8

|

Children Nutrition

As shown in Table 3, most of the food cooked at home was prepared by mothers (47%) and cooks (42%). More than half of the parents considered the home-made meals to be healthy. Most parents (51%) considered their child’s diet to be healthy. As about packing food to school, most of them (59%) did not pack meals for their children for school. The great majority of parents (97%) indicated that they offer guidance for their children to eat healthy.

| Table 3. Information on Food Preparation and Nutrition of Children |

|

Item

|

Description |

%

|

|

Who cooks?

|

Mother |

47

|

|

Cook

|

45 |

| Caregiver |

6

|

|

Father

|

2 |

| Healthy meal |

Yes |

51

|

|

No

|

34 |

| Sometimes |

15

|

|

Pack for school

|

Yes |

35 |

| No |

59

|

|

Sometimes

|

6 |

|

Healthy diet

|

Yes |

51

|

| No |

43

|

|

To a limit

|

6 |

|

Guiding role

|

Yes |

97

|

| Sometimes |

3

|

Association between Awareness of Nutrition Fact Label and Demographics

Data on the relation between demographic characteristics and awareness of nutrition fact labels are shown in Table 4. Gender of respondent parent had no significant effect on the awareness of the nutrition fact label. Meanwhile, there was a significant (p=0.001) effect between age of parents and awareness of nutrition fact label, showing that parents aged >50 are less familiar with the label than younger parents. Marital status had no significant effect on the level of awareness of nutrition fact label. There was a significant effect of the education level of parents on the knowledge of nutrition fact label (p=0.003), meaning that parents who were college graduate parents had more familiarity with such label – compared to parents with less educational levels. With regard to the employment status of parents, working parents were significantly (p=0.047) more familiar with the nutrition fact label than those who were not working. Family income, shopping location, and presence of children health disorders had no significant effect on the awareness of the nutrition fact label. There was a significant difference between the awareness of food label of the parents and allowing children to choose their food. More than 90% of parents who were unfamiliar with the food label allowed their children to choose their food, compared to 76% of parents who were more familiar with the food label. There was a significant effect of the level of awareness of nutrition fact label and allowing children to consume unhealthy food.

| Table 4. Association between Awareness of Nutrition Fact Label and Socio-Demographic Characteristics |

|

Variable

|

Awareness of Nutrition Fact Label (%) |

p Value |

| Yes |

No

|

| Gender |

|

Female

|

70.5 |

61.2 |

NS* |

| Male |

29.5 |

38.8

|

| Age of parents |

|

18-30

|

35.3 |

2.1 |

0.001 |

| 30-45 |

43.1 |

30.6

|

|

>45

|

21.6 |

67.3

|

| Marital status |

|

Married

|

98 |

85.7 |

NS* |

| Divorced |

2 |

12.2

|

|

Widowed

|

0 |

2.1

|

| Education level |

|

Graduate

|

78.5 |

46.9 |

0.003 |

| Undergraduate |

7.9 |

30.6

|

|

High school

|

13.8 |

22.5

|

| Work status |

|

Yes

|

64.7 |

44.9

|

0.047

|

|

No

|

35.3 |

55.1

|

| Family income (KD/mo) |

|

200-<1000

|

17.6 |

28.6

|

NS*

|

|

1000-2000

|

76.5

|

65.3

|

|

>2000

|

5.9 |

6.1

|

| No. of children |

|

1-3

|

66.6 |

32.6

|

0.001

|

|

4-6

|

21.6 |

63.3

|

|

>6

|

11.8 |

4.1

|

| Age of children |

|

2-10

|

64.7 |

42.9 |

0.040 |

| 11-18 |

35.3 |

57.1

|

| Children health disorder |

|

Yes

|

15.7 |

24.5 |

NS* |

| No |

84.3 |

75.5

|

| Shopping location |

|

Cooperative

|

62.8 |

59.2 |

NS* |

| Supermarket |

33.3

|

26.5 |

|

Both

|

3.9 |

14.3

|

| Allowing children to choose their food |

|

Yes

|

76.5 |

91.8 |

0.036 |

| No |

23.5 |

8.2

|

| Allowing children to eat unhealthy food |

|

Yes

|

52.9 |

75.5 |

0.019 |

| No |

47.1 |

24.5

|

| *NS=not significant |

Association between Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables with Demographics

Data on the relationships between demographic characteristics and consumption of fruits and vegetables by children are presented in Table 5. There was a significant effect of the parents age and consumption of enough fruits and vegetables. The older the parents, the more lack of consuming fruits and vegetables. There were no significant effects of the education level, working status, family income or number of children on the consumption of enough fruits and vegetables. However, there was a negative significant association between children’s health disorders and consumption of fruits and vegetables (p=0.001), showing that the majority of children who had disorders don’t consume enough fruits and vegetables, while the majority of healthy children consumed enough fruits and vegetables. There was a significance effect between children who choose their own food and consumption of fruits and vegetables (p =0.001). There was significance effect between children who take meals to school and consumption of fruits and vegetables (p =0.003), children who packed to school consume more fruits and vegetables, compared to those who did not. Children who were allowed to consume unhealthy food did not have enough intakes of both fruits and vegetables, compared to those children who were not consuming unhealthy foods.

| Table 5. Relationship between Some Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Consumption of Enough Fruits and Vegetables |

|

Variable

|

Consumption of Enough Fruits and Vegetables

|

p Value |

| Fruits |

Vegetables |

Both

|

None

|

| Age of parents |

|

18-30

|

20.0 |

15.6 |

80.0 |

13.9 |

0.017 |

| 30-45 |

50.0 |

34.4 |

0.0

|

37.2

|

|

>45

|

30.0 |

50.0 |

20.0

|

48.9

|

| Education level |

|

Graduate

|

70.0 |

56.3 |

100.0 |

60.5 |

NS* |

| Undergraduate |

20.0 |

15.6

|

0.0

|

23.3

|

|

High school

|

10.0 |

28.1 |

0.0

|

16.2

|

| Work status |

|

Yes

|

50.0 |

56.3 |

80.0 |

53.5 |

NS* |

| No |

50.0 |

43.7 |

20.0

|

46.5

|

| Family income (KD/mo) |

|

200-<1000

|

35.0 |

15.6 |

20.0 |

23.3 |

NS* |

| 1000-2000 |

60.0 |

75.0 |

80.0

|

72.1

|

|

>2000

|

5.0 |

9.4 |

0.0

|

4.6

|

| No. of children |

|

1-3

|

55.0 |

50.0 |

80.0 |

44.2 |

NS* |

| 4-6 |

45.0 |

40.6

|

0.0

|

46.5

|

|

>6

|

0.0 |

9.4

|

20.0

|

2.3

|

| Children health disorder |

|

Yes

|

0.0 |

6.3 |

0.0 |

41.9 |

0.001 |

| No |

100.0 |

93.7 |

100.0

|

58.1

|

| Pack for school |

|

Yes

|

55.0 |

25.0 |

0.0 |

37.2 |

0.003 |

| No |

35.0 |

71.9 |

60.0

|

60.5

|

|

Sometimes

|

10.0 |

3.1 |

40.0

|

2.3

|

| Allowing children to choose their food |

|

Yes

|

95.0 |

87.5 |

20.0 |

83.7 |

0.001 |

| No |

5.0 |

12.5 |

80.0

|

16.3

|

| Allowing children to eat unhealthy food |

|

Yes

|

65.0 |

62.5 |

0.0 |

72.0 |

0.017 |

| No |

35.0 |

37.5 |

100.0

|

28.0

|

| *NS=not significant |

Association of the Source of Nutrition Knowledge with Shopping Awareness

The relationships between the source of nutrition information and different traits of interest are shown in Table 6. There was no significant effect of the source of nutrition information and the most important information in the nutrition fact label from the parents’ point of view. Also, results showed a non-significant relationship between the source of nutrition information and the purchasing of ready to eat meals, most eaten food groups, packing food to school, allowing children to choose their food, parents guiding their children, or allowing children to consume non-healthy food.

| Table 6. Relationship between the Source of Nutrition Knowledge and Shopping Awareness |

| Variable |

Source of Nutrition Knowledge |

p Value |

| Media |

Books and Doctors |

Friends and Family |

| Most important information in the nutrition fact label |

| All |

1.50 |

16.0 |

0.0 |

NS* |

| Calories |

26.9 |

16.0 |

50.0 |

| Fat |

17.9 |

12.0 |

25.0 |

| Sugar |

17.9 |

16.0 |

0.0 |

| Salt |

3.0 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

| None |

32.8 |

36.0 |

25.0 |

| Shopping for nutrient claim |

| All |

4.5 |

8.0 |

50.0 |

0.022 |

| Cholesterol-free |

3.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Low fat |

46.4 |

44.0 |

25.0 |

| Low Sugar |

3.0 |

0.0 |

12.5 |

| Natural |

7.4 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

| None |

23.9 |

36.0 |

12.5 |

| Organic |

5.9 |

8.0 |

0.0 |

| Other |

5.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Knowledge of food ingredient label |

| Yes |

46.3 |

64.0 |

87.5 |

0.044 |

| No |

53.7 |

36.0 |

12.5 |

| If yes, which ingredient |

| Additives |

40.3 |

72.0 |

37.5 |

0.001 |

| Allergy components |

5.9 |

0.0 |

25.0 |

| Sugar |

3.0 |

0.0 |

25.0 |

| None |

50.8 |

28.0 |

12.5 |

| Purchasing ready to eat meals |

| Yes |

59.7 |

60.0 |

37.5 |

NS* |

| No |

40.3 |

40.0 |

62.5 |

| Most eaten food groups |

| All |

3.0 |

8.0 |

0.0 |

NS* |

| Dairy |

5.9 |

20.0 |

25.0 |

| Fruits and vegetables |

9.0 |

8.0 |

12.5 |

| Grains |

16.4 |

8.0 |

37.5 |

| Meat |

65.7 |

56.0 |

25.0 |

| Pack for school |

| Yes |

34.3 |

28.0 |

62.5 |

NS* |

| No |

61.2 |

60.0 |

37.5 |

| Sometimes |

4.5 |

12.0 |

0.0 |

| Allowing children to choose their food |

| Yes |

83.6 |

84.0 |

87.5 |

NS* |

| No |

16.4 |

16.0 |

12.0 |

| Parents guiding children |

| Yes |

95.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

NS* |

| No |

4.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Allowing children to consume unhealthy choices |

| Yes |

62.7 |

60.0 |

87.5 |

NS* |

| No |

37.3 |

40.0 |

12.2 |

| *NS=not significant |

However, there was a significance effect of the source of nutrition information and knowledge of food ingredient label – with food additives being the most important ingredients of concern. There were significant relationships between consumption of junk foods, soft drinks, and juices and “where do you get your nutrition information” (p =0.032), which means that the parents who allow their children to consume junk foods and sugary drinks get their nutrition information from the media. Meanwhile, parents who do not allow their children to consume junk foods get their nutrition information from reliable sources such as books and family doctors and trusted media sites. What is presented in the media in this regard has a powerful impact and the highest influence on children and their parents.

DISCUSSION

The results confirm that the knowledge level of Kuwaiti parents is considerably limited and needs improvement.5 One of the findings is that younger parents generally had more nutritional awareness than older parents, although a large percentage still did not pack a healthy lunch for their children to school. Instead, the children were given pocket money and left to select what they wanted from the school’s canteen; which, according to some parents, consisted of the fast-food type and unhealthy food choices. Some of the parents had a successful influence on their children and were able to feed their children what they considered to be “enough” fruits and vegetables. Other parents were allowing their children to consume as much junk food items as they please only because they do not consider themselves to be “well-rested” enough to deal with their children’s desires. Several parents explained that they understand these foods were harmful, but they did not want to deprive their kids from foods that other children are consuming.

One of the findings is that out of the 100 parents who participated and were questioned about their kid’s health status, 20% parents mentioned that their kids were suffering from nutrition-related disorders such as obesity, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and food allergies.

Age is a significant factor in determining the level of knowledge and nutritional awareness,18 which this study has confirmed. Older parents who were 45 years and above have nutritional knowledge that can be linked to tradition and culture. Only two elderly parents had some idea about “modern” nutrition from interacting with their grandchildren and keeping up with new information through the media. As for the younger parents, they had a higher level of education, most of which were university graduates, and a higher-level of nutritional awareness. They read food labels and could identify several aspects of food and chemical additives. They also chose to stay away from the supposedly dangerous chemicals such as monosodium glutamate (MSG). Many of them were up-to-date and were able to discuss recent controversies surrounding nutritional information and latest findings. When questioned about their source of nutrition information and knowledge, approximately 54% of both parents of all ages stated that they got most of the information from the media such as: Instagram, WhatsApp broadcasts, and YouTube videos. Furthermore, social media has the upper hand in spreading the nutritional awareness in Kuwait, though there are both advantages and disadvantages to this phenomenon.19 The people using these social media tools are giving out straightforward and clear information to other users and viewers. These tools allow people to access information in a faster manner, which is demanded, in this modern age of the technological revolution. Unfortunately, people can always give nutritional advice whether they are eligible and accredited or not.20,21 There is not sufficient awareness and knowledge in the Kuwaiti society about accreditation and people have a preference for fast results; therefore, accepting any information from anyone and naivelyassuming that the source has enough credibility to go on posting such information about nutrition on the internet. Visual images posted on social media also have shown to be a strong influence in society by promising false fast results and gaining many followers.22 The rest of the parents refer to books, friends, or family doctors for their information due to the prevalence of medical and nutritional disorders in either the parents or their children. Additionally, a large proportion of parents who are working are susceptible to buy ready-to-eat meals than the non-working parents. Working parents state that they do not have enough time to prepare food for their children, thus resorting to opt for the easier, more convenient options regardless of their lack of healthy selections. Due to their free time, non-working parents, especially mothers, take the time to prepare homemade meals for their children despite that these meals are not necessarily healthy. Also, non-working parents have the time to prepare lunch boxes for their children to school – while working parents usually are content with giving their children pocket money. The components of the packed lunch boxes are usually a cheese sandwich, some nuts and a small container of milk or juice. The addition of fruits and vegetables are scarce in their children’s menu for the school lunch boxes. Parents of ages ranging from 18-45 years were shown to pack food for their kids to school more frequently than older parents.

Fruits and vegetables are important for children’s health and their growth by providing their bodies with essential nutrients such as vitamins and minerals.7,10 The interviewed parents did not fully understand the importance of the serving sizes for fruits and vegetables and stated that their children consume a subjective “enough” each day. One apple and one potato could be enough in the parents’ understanding and this is not sufficient at all according to choosemyplate.gov (USA) – which states that half of the plate should be filled with a broad selection of fruits and vegetables.23,24 During the interview, five of the parents mentioned that their children were obese and that they do not consume any fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the Kuwaiti children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables is not adequate, and the serving sizes and portions of food consumed by their children are worryingly unknown to the parents. Most parents, especially working parents, were not aware of what their children consume and were estimating their portion sizes for the questionnaire.

Many working parents were shopping for ready-to-eat meals. They explained that they do not have enough time to cook for their children and there is a caregiver that cooks for their children instead. They also explained that they could not be sure that their kids are consuming the caregiver’s food; therefore, they would buy the ready-to-eat meals to encourage kids to eat. Ready-to-eat meals are usually processed packaged meals such as frozen pizza, frozen nuggets, packaged soups, ready to use syrups.25 Similarly, they include junk foods such as sugary juices, fizzy drinks, wrapped sweets, chips, cookies, and chocolates.26 Those ready-to-eat meals are inappropriate for children to thrive on due to many health-disrupting affects.24,27 For example, foods that we may consider to be healthy can be actually harmful – such as the case of most packaged muesli, which contain soy lecithin, a byproduct of the soybean oil production.28 Soy lecithin, which is used to bind the various food ingredients together, was found to have side effects such as changes in weight loss and gain, loss of appetite, occasional nausea, dizziness, vomiting and confusion.28 Furthermore, most coloring agents are harmful to children according to a review that has been done to evaluate the effect of artificial coloring on children and whether if such has a harmful effect on children? It was found that these substances can bind to human serum albumin and cause health problems. Artificial dyes in foods were found to cause attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children – when compared to natural coloring.29 Consequently, several studies showed evidence that children’s consumption of processed foods can and will eventually result in behavioral problems.30 Finally, there was no relationship between the level of family income and the susceptibility to buy ready-to-eat meals in this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore aspects of parents’ behavior in relation to their children nutrition in Kuwait. Further expanded studies are recommended in this area, which would include wider segments of the population in the country. Emphasis of future studies would be on enhancing parents’ awareness and knowledge of nutrition and on the significance of following healthy dietary habits and lifestyle for themselves and their growing children.

CONCLUSION

The knowledge and comprehension of nutritional information of parents highly influences their children’s consumption of food choices such as: nutritious foods, and or non-healthy food items – hence shaping their food eating patterns, food choices, as well as their current and future health. Many parents’ grocery shopping habits were analyzed along with their nutritional knowledge and their children’s eating patterns for examining the influence of parent’s nutritional knowledge on their children’s health in the Kuwaiti society. Both male and female parents of Kuwaiti nationality, were interviewed in several different supermarkets and cooperatives for this study and results were analyzed with the use of credible statistical tools. Most parents were found to practice negative shopping habits, whether they had some nutritional information or not, depending on several influences such as age, working hours, and the time and level of effort they can devote. Many do not pack lunches for children to school and many indulge in buying ready-to-eat meals for their household. Several parents showed knowledge in the nutrition field, especially those that were in the younger age ranges and practiced healthy habits such as cooking for their children themselves, watching what their children eat?, packed healthy lunches to school and showing the children good examples. Both of those who were knowledgeable and those that had scarce knowledge in nutrition received their information mainly from the media. These findings underline the need for more awareness of nutrition among parents and an emphasis on the role of healthy nutrition and lifestyle in disease prevention. Different public health approaches can be employed to enhance the significance of sound nutrition and its positive effect on general health. Nowadays, the available electronic media can be the vehicle for enhancing such a relationship and for providing credible and scientifically-based information. This study opens the door for many large scale and more comprehensive studies in this important-to-all area. Such studies may better be longitudinal, rather than being cross sectional – to allow for analysis of the health of children in relation to their prolonged food choices.

LIMITATIONS

This study was primarily limited by the method of data collecting. Self-reporting was the main method instead of actual food label reading test and visual examples for food serving sizes. When parents were questioned if they included processed foods, they reported in the negative – but when given examples, the parents changed their answers. Most parents were mainly shopping for ready-to-eat meals and only a few had healthy baskets with fresh produce. Another possible improvement to the study could have been interviewing the participants in a quieter corner setting, which could elicit greater information regarding the participant’s knowledge and attitudes. Many parents were in a hurry to shop and to go back to their homes – thus answering the questions vaguely and quickly. Some parents’ reports were false, and the cart they pushed around in the grocery store did not evidence what they stated. They had mostly ready-to-eat meals and junk food items while stating their kids love consuming fruits and vegetables and claimed that they witnessed their children consuming healthy food. Also, it would have been desired to interview the children of the participating parents. The number of subjects of this study is not considered to be large; however, such is considered satisfactory with experienced time constraints. Meanwhile, being the first study of its kind in Kuwait, there can be further studies that explore several perspectives and the many interchanging and interfering factors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

This work was carried out as a capstone project when the first 4 authors were senior students in nutrition at the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Life Sciences, Kuwait University, Kuwait. Eman Al-Awadhi searched for relevant recent studies and reviewed the different versions of this manuscript. Farouk El-Sabban supervised the capstone project, coordinated all efforts, and edited the final version of this manuscript. All authors read and approved of this manuscript for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank Dr. Al-Asousi M, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Life Sciences, Kuwait University, Kuwait, for her help in preparing the first draft of this manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in conducting this study or in publishing its results.