INTRODUCTION

Gender-based violence by intimate or non-intimate partners is both a violation of human rights and a public health priority.1 Worldwide, 15-71% of women suffer physical, psychological or sexual intimate partner violence.2 Studies suggest that 33-60% of Indian women have faced spousal violence,3,4,5,6 and that 28% of ever-married urban women have experienced physical violence in the past year.7 According to the National Crime Investigation Bureau Records, there has been a 120% increase in reported gender-based crimes in India during the last decade (2003-2013). More than three hundred thousand women (309,546) in the year 2013 reported crimes against them. Crime against women (reported cases) in Maharashtra (considered one of the developed states in the country) in 2013 saw an increase of 46.79% as compared to 2012. In the year 2013, sexual assault accounted for 17.75% of all the gender based crime in Mumbai. These figures indicate the global and domestic magnitude and expanse of the problem.8,9

The issue of violence against women and children cuts across caste, culture and geographical boundaries and has been universally accepted as a violation of gross human rights. There is a growing understanding with academics, practitioners and researchers that primary prevention is the step towards reduction in or elimination of gender-based violence. While the long term goal is elimination of gender-based violence, it has been a daunting task to work out different strategies at the individual, family, community and institutional level for primary prevention, moreover to develop an understanding of whether these strategies work or not.10

Presently, the global discourse focuses on establishing impact indicators to measure reduction in gender-based violence in communities. Considering the volatile nature of the issue and its likelihood of recurrence it has been challenging to arrive at indicators that allow practitioners and researchers to measure the reduction. The WHO recommends that we establish systems for data collection to monitor violence against women and the attitudes and beliefs that perpetuate it. “Surveillance is a critical element of a public health approach as it allows trends to be monitored and the impact of interventions to be assessed”.11 Until now, there are three ways in which data has been collected: disclosure, professional alertness, and surveys. This has not led to a breakthrough in understanding pathways to impact.

In absence of proximal and distal indicators that measure reduction, increased reporting of cases becomes an important measure of assessing the impact of primary prevention.12 The socio-ecological model promulgates a framework on prevention of violence. Despite a divergence of approaches, consensus is emerging that working to prevent violence before it starts must be a priority.13 Programmes have started incorporating primary prevention strategies along with secondary and tertiary prevention.14

SNEHA’s Program on Prevention of Violence against Women and Children aims to develop high-impact strategies for primary prevention, ensure survivors’ access to protection and justice, empower women to claim their rights, mobilise communities around ‘zero tolerance for violence’, and respond to the needs and rights of excluded and neglected groups. The program prioritises enhanced co-ordination of the state response to crimes against women through a convergence approach that works with government and public systems to reinforce their roles in assuring basic social, civil and economic security to women and children. Counselling centres are run in four locations – close to or based in urban informal settlements – in Mumbai, and community mobilisation activities are carried out in parallel.

SNEHA believes that investing in women’s health is essential to building viable urban communities. SNEHA also targets other large public health areas: maternal and newborn health, child health and nutrition, adolescent health and sexuality.

Mumbai, a city located on the western coast of India, is the capital of Maharashtra. It has an estimated city population of 18.4 million and metropolitan area population of 20.7 million as per the government census of 2011.15 According to a Harvard Business School research, in 2001, an estimated 924 million people lived in slums across the world, 60% of them in Asia. Mumbai, with 49% of its population living in 2,000 slum pockets, had the largest absolute number and the largest proportion of slum dwellers in the world.16

The program was started in a large urban informal settlement of Dharavi in Mumbai that comprises of 750,000 to one million people. It hosts 140,000 houses sprawled over 535 acres.17 The constraints of living in cramped conditions, deprivation and issues of survival make the women and children vulnerable to abuse and violence.

The three main components of the program are counselling and crisis intervention services for survivors of gender based violence, community mobilisation and institutional response to gender based violence. Through community organisation activities we have formed groups of women, youth and men who identify, intervene and refer cases of violence. We work with the police, health care providers and the legal authorities to enable them to recognise gender-based violence as a public issue, so as to understand their role as a service provider. Our team currently compromises of a Program Director, six mid-management staff members, one research officer, 18 counsellors, 25 front-line workers (community organisers) and 10 project officers.

A retrospective study of program data strengthened our conviction that it is important to work at all levels – individual, community, and societal – to address gender-based violence, and of the need for an intervention program that prioritises coordination across civil society.18

This review is of the aforementioned programme on prevention of violence against women that primarily examines the scope and impact of a complex intervention in a complex urban setting. The review discusses the evolution of the programme and the primary, secondary and tertiary interventions executed to create an environment in which women felt safe to seek help. The content of the review have been derived from a complex collection of reports, documents, publications and, most importantly, individual and collective narratives. This review aims to locate the program’s history in a context and delineate those features that are integral to the program’s work on prevention.

PROGRAM STRATEGIES AND INTERVENTIONS

Prevention includes a wide range of activities – known as “interventions” – aimed at reducing risks or threats to health and well-being are grouped into three categories: primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. Primary prevention targets specific causes and risk factors for gender-based violence, but also aims to promote healthy behaviours, increase knowledge of rights and entitlements, improve women’s capacity to counteract violence, and foster safe environments that reduce the risk of violence, for instance, through creating network that offer support to women. We have developed primary preventive interventions through community outreach programs, campaigns and, in the last year, we have piloted mobile-based technology for crowd sourcing cases of gender-based violence. We are now in the process of developing our own integrated mobile application that will be used by the SNEHA Sanginis (community women volunteers) and our front-line workers to identify, intervene in and refer cases of gender-based violence.

Our Services: Counselling and Crisis Intervention

The National Family Health Survey – III (2005-2006) reports partner violence in 37% of ever married women and 16% of never married women who have experienced violence from husbands and close family members.6 The situation is likely to be much worse because surveys underestimate the occurrence of violence.19 Women do not tell, and they do not seek help. Only 24% of urban Indian women who said that they had survived violence sought help from anyone, mostly (71%) within their own family. Hardly any sought help from professionals (2% from the police, 0.6% from lawyers, 0.6% from social service organisations and 0.4% from doctors).6

Research has shown that – globally – women are more likely to access the public health facility when they face violence.20.21 In a study conducted in a public hospital and community health centres in Thane district, it was found that doctors had recorded domestic violence as the causal factor of injury in only 13.5 % of cases.22 The researchers found that in an additional 38.8 per cent cases, women were most likely victims of domestic violence, but this was not reflected in the hospital records.21 In this case the doctors had overlooked the presence of violence in a substantial number of cases. Jaswal found that both probable cases and recorded cases of domestic violence constituted nearly 53% of the total medico legal cases.22

We started the counselling and crisis intervention centre for women and children in distress, as well as temporary shelter amenities in a public health facility. These were located in the midst of the Dharavi community. When women were referred by doctors to the counselling centre, they said that managing their situation of domestic violence was not their primary need. There was a high premium on pecuniary benefits like acquiring financial aid for their existence or donation for their children’s education. Encouraging the survivors to speak up against the violence they were facing, and educating them about their rights evolved into prevention strategies. Promoting attitudes, beliefs and behaviours with the survivor and the perpetrator helped to prevent further violence from escalating into major crisis. The first year showed that out of 78 cases, 34 cases were referred to the counselling centre from the health care facility where we were based.

Our work on counselling focuses on helping the survivor work through her relationships with the perpetrator and significant others, if the survivor chooses to remain in that relationship. The Program works with a pro-woman approach, with her rights and choices informing the interventions that are carried out. The response to violence in women’s lives is strengthened with a holistic approach that addresses women’s immediate and long-term needs, recognises the emotional trauma they may suffer and challenges the stigma that accompanies gender-based violence. It is the woman who drives the outcomes of the intervention and counselling as we put the woman’s right to choose and agency at the centre of our work. Providing the temporary shelter service in itself turned out to be an intervention and a prevention strategy to help women get out of violent situations. The prevention strategies designed with the survivors and perpetrators were family counselling, conflict resolution, and fostering problem solving skills to promote healthy relationships. We understood the importance of a comprehensive service-delivery model for survivors of violence. This prompted us to collaborate with the District Legal Services Authority to provide fee legal aid and legal counselling to women and assist them in filing cases.

We have faced ethical dilemmas that have shaped the evolution of the Program. The deep-rooted and pervasive patriarchal structure often assumed the woman’s choices and rights as secondary to that of her family. This meant that the woman was not always at liberty to exercise her choice and we had to work with her family to convince them to support her or allow her basic freedom and rights. On the other hand, getting the community involved in addressing gender-based violence and asking them to intervene meant that the woman’s rights to privacy and self-determination were compromised. Often the violence situations played out in an unfavourable manner for the woman whilst reaching out for help especially when it impinged on the interests of powerful people.

The situations are precarious and often require sensitive, skilful handling and negotiation with the perpetrators to stop violence. Ethical considerations are core to the execution of the program. The women are assured complete confidentiality and their information is not shared with the perpetrator’s family, community members or the media under any circumstances. They are also informed that the information is anonymised on the case sheet and it could be used for analysis of data with an objective to improvise the quality of service provision. We inform them about their right to access their records for evidence building of their legal cases. We have ensured to take consent from all women who access our services; in case of minor girls consent was taken from their legal guardian.

Being there for the Community: Immediate Crisis Response

Intervening in cases of gender based violence at the time of its occurrence is an effective way of connecting with communities. It allows us to confront the issue openly and makes it more visible. The murder of a young, married woman from the nearby community in 2002 was the first case of homicide that SNEHA was asked to be involved in. It was her family and the community who asked for assistance from the counselling centre. The intervention required was beyond our remit at that point of time as it was highly complex and challenged our concept of service delivery. However, we could not ignore the need of the community so we chose to intervene, along with the family and the local community. We networked with the police and the legal systems to ensure that the documentation was in order and complete, leaving no chance for the perpetrators to be released.

Intervening in this case connected us more with the community, police and the legal systems and led to a major shift in the program’s vision. We understood the importance of primary prevention and the program evolved strategies to work on primary prevention. This helped us to engage and move people to commit time and energy towards this issue. Over the years we have intervened in cases of homicide and suicide as soon as we hear about it. Although we meant to preserve the centre’s services as therapeutic, the community member’s presence and involvement in cases transformed the counselling centre’s profile into a community counselling centre. In few cases the involvement elicited from key people (i.e. neighbourhood, close relatives, leaders of the community) helped in arriving at plausible solutions for the women and the monitoring by community members evolved as a strategy to prevent further violence from taking place. Our observations corroborate with the SASA! Study, a pair-matched cluster randomised controlled trial, who listed out appropriate actions that were encouraged by the intervention.23

Primary prevention activities raise expectations and as a result community members identify and inform about cases where women are facing violence in their homes without taking the consent of that woman. Our thrust on eliciting community member’s participation and contribution has led to difficulties in maintaining confidentiality of the case. The community members involved in the case expect us to share the case details and there is a probable danger of the case being exposed to the community. The organisation therefore has to tread the fine line between ensuring the confidentiality of the woman and keeping community members, engaged and motivated to continue reporting cases of gender-based violence.

Our Participatory Processes: Urban Micro Planning

Lack of acknowledgement of gender-based violence as a public issue does not encourage people to intervene. Often any intervention is considered to be interference by the family and society. Our interactions with women showed that day to day survival issue was more pressing to women rather than recognising the need to raise their voice against violence.

We thus devised a different, more innovative approach to build relationships with the community, by facilitating their involvement in the process of micro planning. We used Participatory Learning and Action techniques in this process which garnered large participation from the community. Participatory Learning and Action seeks to share the community’s multi-dimensional experience, by studying the panorama of micro-environments that they are part of, which may have not been considered in the past. In our experience, Participatory Learning and Action is a rapid assessment tool for relief work, community development, health programs, small enterprise development, education and many other issues. This exercise has been very instrumental in shaping our primary prevention work with the communities.

The processes led to creation of a large pool of volunteers who were motivated to work as an action system within their localities on issues they identified during the process. The issue of gender-based violence and women’s safety emerged as one of the critical issues. This process of seeking community involvement led to a positive shift in the community’s acceptance of gender-based violence as a problem to address.

Thus, SNEHA’s Program on gender-based violence also shifted from a purely centre-based, service-delivery approach to a programme which has a strong community orientation, an emphasis on prevention, and works towards building sustainability of community-owned interventions. The change began in 2003. While counselling services remain key to the intervention; they are embedded in an understanding of community dynamics. We provided on-going support to community-based groups and volunteers. Awareness generation among women, men and youth creates a context for empowering survivors to take action and enabling them to negotiate more effectively with perpetrators and their families.

Aiming for Change: Challenging Gender Norms through Community Mobilisation

The major thrust of the program shifted to community mobilisation after we had carried out microplanning processes. It was important for us to facilitate a process through which action is stimulated by the community itself and evaluated by individuals, groups and organisations. It was important to empower the community to bring about a change in the existing situation. In order to stimulate this action, the primary step was to challenge gender norms which would give them an opportunity to unlearn stereotypical beliefs and practices and move towards gender transformative attitudes.

Among strategies to shift norms, attitudes and beliefs related to gender, the two that have been most rigorously evaluated are: 1) small group, participatory workshops designed to challenge existing beliefs, build pro social skills, promote reflection and debate, and encourage collective action; and 2) larger-scale “edutainment” or campaign efforts coupled with efforts to reinforce media messages through street theatre, discussion groups, cultivation of change agents and print materials. Both these strategies have demonstrated modest changes in reported attitudes and beliefs.24

We devised campaigns to talk about gender based violence as a human rights’ issue. We carried out community organisation activities – such as corner meetings (informal, small group meetings held in the community) – preceding the campaign which led to greater participation from the community members.

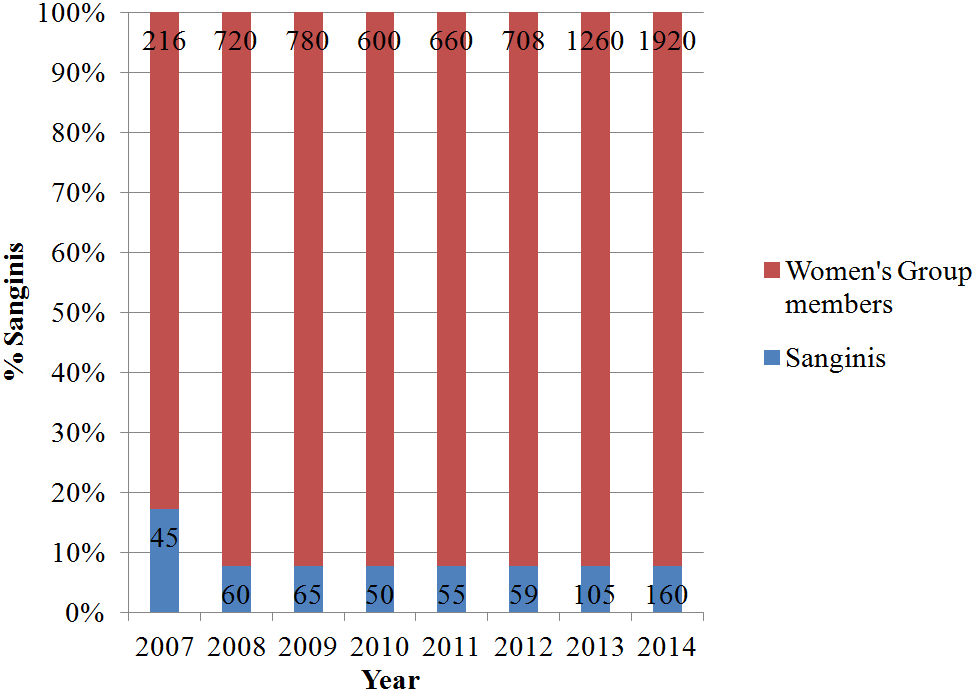

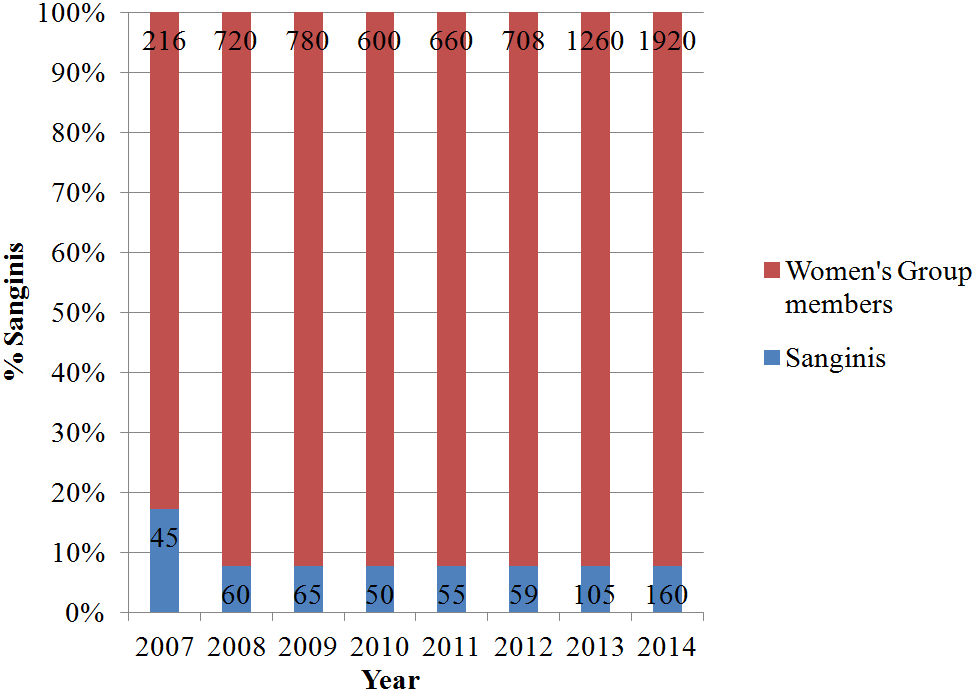

Creating women’s agency through formation of women’s groups and networks was a critical strategy. In 2007, we initiated the process of setting up small groups by forming 18 women’s groups, and training 84 women to identify, refer and intervene in cases of gender based violence in their respective communities, of which 45 emerged as Sanginis (community women volunteers).With regards to our community volunteers we have signed a formal agreement with them about voluntary consent; they agree to maintain confidentiality and a sensitive approach. The Sanginis facilitate initial crisis response in cases of gender based violence. The strategy to bring women together now forms the basic social infrastructure upon which the Program operates. We presently lead 130 women’s groups whose members meet at least eight times a year to find plausible solutions to take collective action against incidents of gender-based violence in their community. SNEHA has played – and continues to play – an active and important role in forming these groups and networks across Dharavi and reaching out to women through them. The emphasis was not on simply forming a space where women could come out of the house, but one where they could actively assist one another in times of need, and take responsibility of their community themselves.

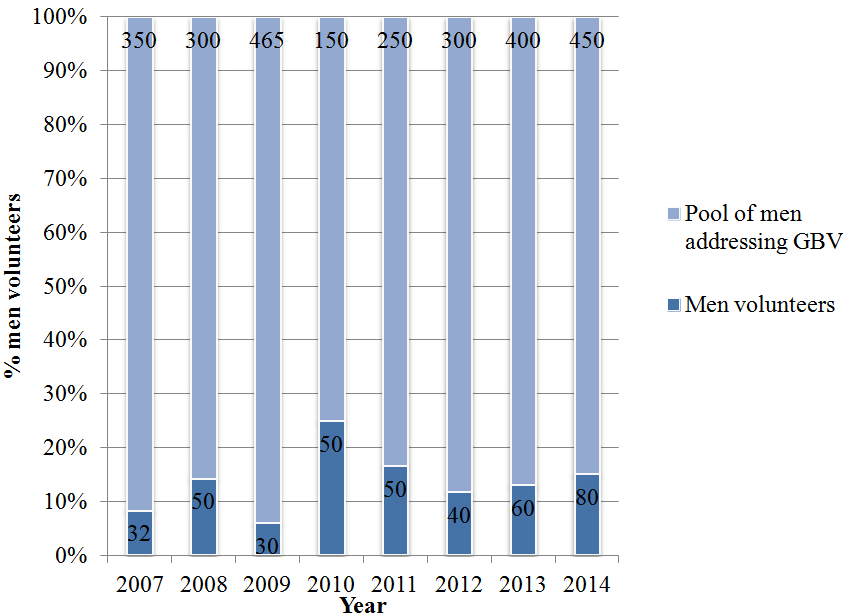

Gender Transformative Approach: Generating Male Allies

Historically, organisations have focused individual and community interventions on women to address gender-based violence. There is a recent shift globally to engage men and boys to prevent gender based violence. The discourse at United Nations conventions and around the Millennium Development Goals has been on evolving strategies to work with men and boys to challenge social norms about gender and masculinity. SNEHA, too, works with men who account for the bulk of the group of perpetrators of violence. We have worked with over 4000 perpetrators of violence, with men being the primary perpetrator and family members as secondary perpetrators. In-depth work with men gives us greater insight into the general attitudes and beliefs that men hold on gender and gender-based violence, and into their abilities to bring about change, even if it means in their own lives, in their inter-personal relationships, and their family life. Our experience shows that work with men is complex, ambitious and provocative and is generating important synergies in the community.

It was difficult in the beginning to work with men in the local community as they failed to see their role in addressal of gender-based violence. The micro planning processes carried out helped to mobilise men to work with us. There was a covert resistance to work on gender based violence. Issues of sustainable development interested them. We formed action committees of men and women to work on non-threatening issues of sanitation, slum redevelopment and such others. At every possible opportunity, such as when the committee desired to work on a sustainable development issue that concerned them, we facilitated workshops to draw attention to gender inequities in existing structures that perpetuated violence against women.

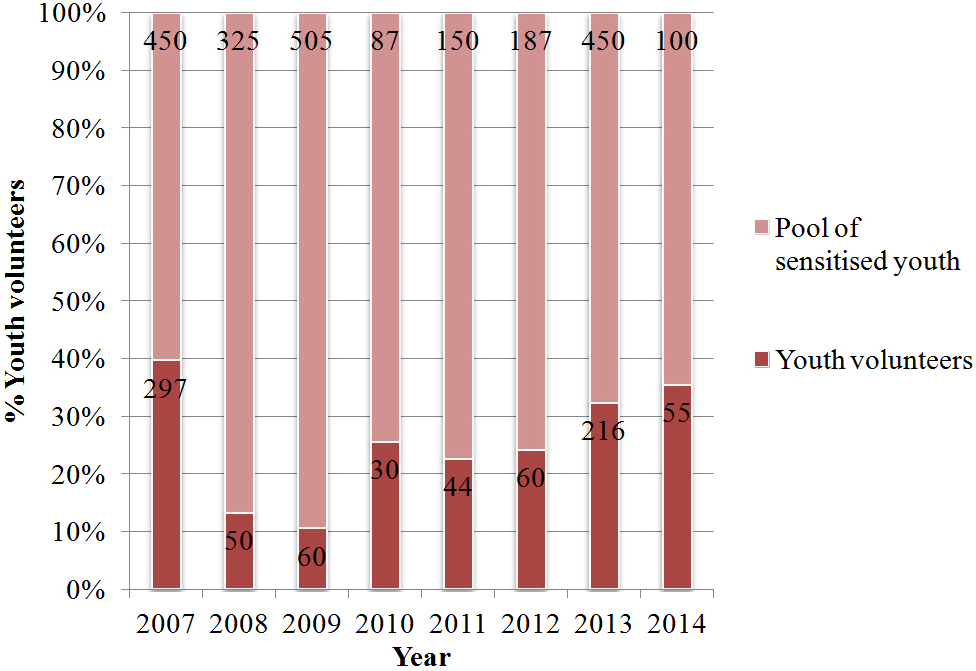

Ensuring a Better Future: Creating Youth Animators

The micro planning processes also led to the formation of a network of youth volunteers, both girls and boys, who were then sensitised and trained to carry out prevention activities in the community through street theatre. These young people continued to associate with the Program as theatre performers, even after the microplanning processes were over. They became involved in sensitising different groups – school students, local residents, and the general public at SNEHA campaigns (with an average of 300 men, women and children attending each campaign, and at least five campaigns conducted a year, we have reached out to over 300,794 people through this medium over the past years) – on issues related to gender and violence against women. These youth activists, who are not only change agents, but also the beneficiaries of SNEHA’s work on prevention of violence, underwent training on the issues to ensure that they are aligned with our approach to gender and violence and believe in what they are propagating. The youth gradually understood the far-reaching and deeply entrenched effects of patriarchy and its intersection with gender-based violence. Through the medium of theatre, they developed not only subject knowledge but the conviction and confidence to talk about violence against women and girls. The change we observed was when they started referring cases of violence to SNEHA. Often, these were their mothers, sisters, female relatives and friends whom they were trying to help. Due to the positive reception of the work aimed at young people, both by parents and the young people themselves, we decided to start a separate program – EHSAS (Empowerment, Health and Sexuality of Adolescents) – comprising of projects executed in different locations across Mumbai.

MEASURING INCREASED REPORTING OF VIOLENCE

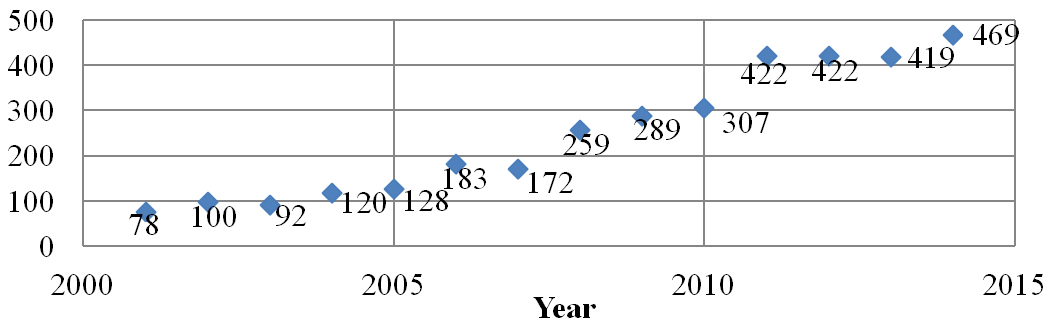

It has been difficult for us to measure the impact of our work considering the complexity of the issue and the vested interest of various stakeholders. What could be safely inferred is that the implementation of a multi-layered and multi-stranded approach has led to an increase in reporting of cases. The most significant measure of the success of the program can be seen by the steady increase in the number of cases approaching SNEHA for help over the past 14 years.

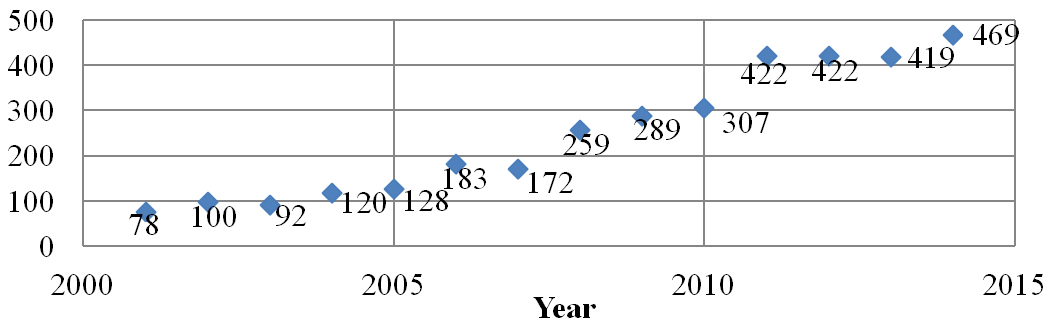

Figure 1 shows an upward trend in the number of cases reported to SNEHA’s counselling centre. One can observe a 51% increase in the number of cases from 2007 to 2008 as this was the time when we carried out large scale microplanning exercises. Institutionalising community mobilisation in the Program has resulted in an increase in reporting of cases of gender-based violence.

Figure 1: Number of cases reported per year, n=3460.

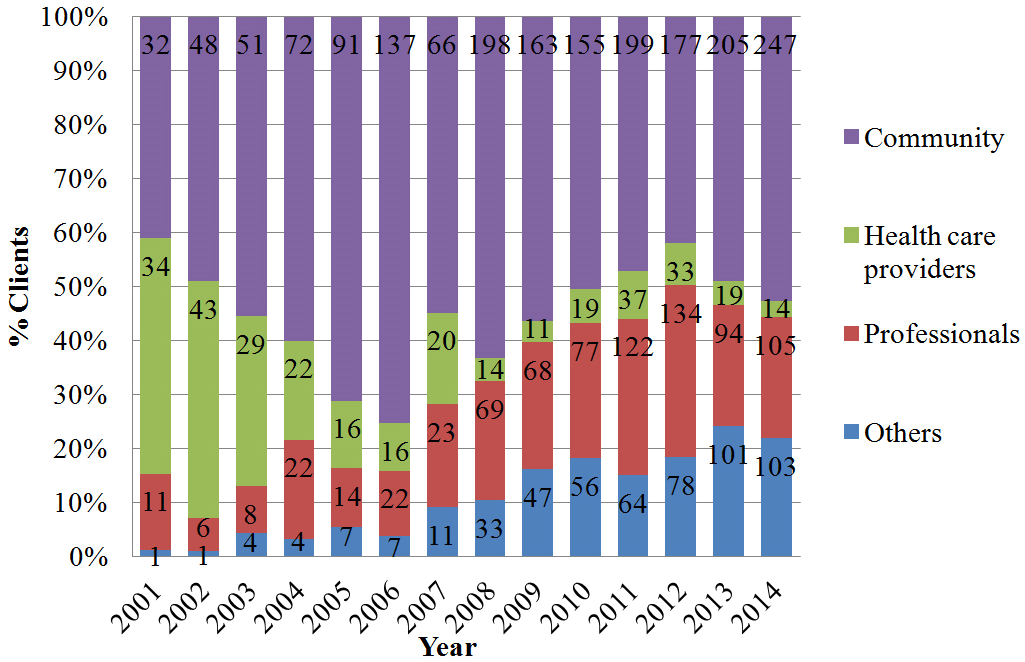

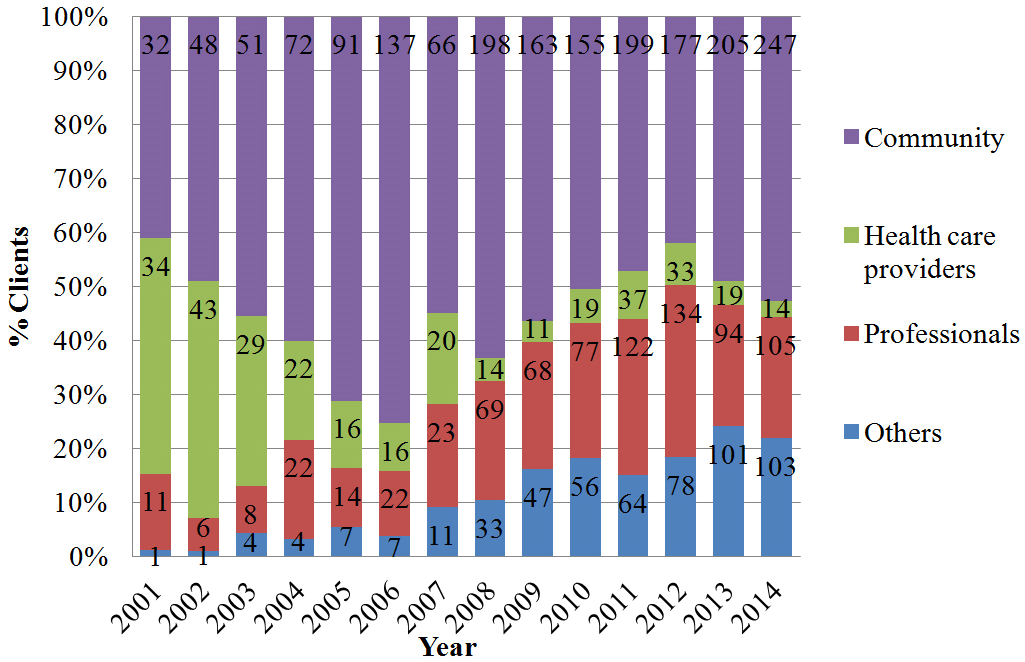

The community accounts for the largest source of referrals to the counselling centre. Figure 2 shows that – in the initial years – the proportion of referrals from the health care providers was high. A steady increase in referrals from the community could be attributed to former clients (survivors approaching SNEHA for help) who were satisfied with the service and referred other women, and community health volunteers who were sensitised and trained to identify cases of violence. The formation of women’s groups in different areas and working with caste panchayats (an extra-constitutional body that follows a system of social administration based on lineage) led to an increase in visibility of the counselling centre and consequently referrals increased. The micro planning process in 2007 established credibility of the program. The women’s groups and the action committees formed acknowledged the issue and contributed in referral of cases to the centre. In the category of ‘others’, we have included online referrals (self or other) starting in 2010. While it currently accounts for only 21% (crisis helpline-49%, referrals by those other than the survivor -30%), it shows the steadiest upward trend.

Figure 2: Routes by which women in crisis approached SNEHA

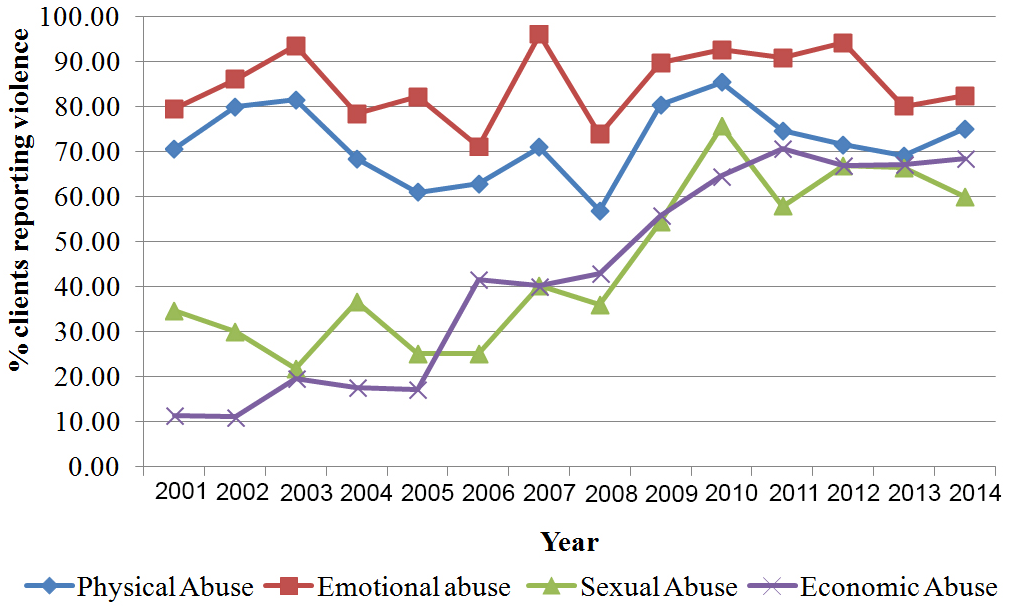

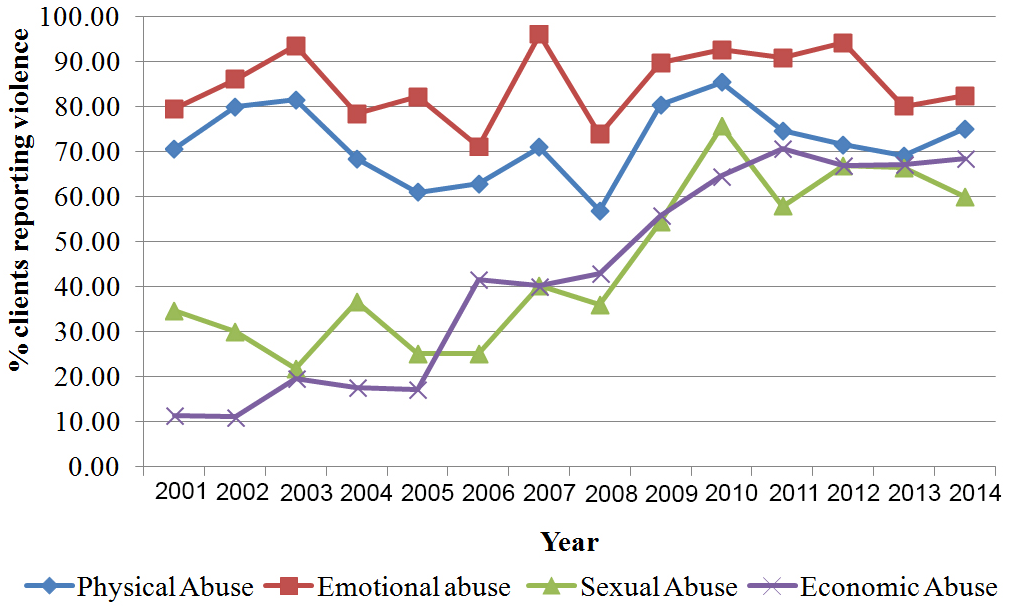

In keeping with the National Family Health Survey and United Nations’ guidelines, we define abuse as emotional, physical or sexual, as well as economic. There has been a consistently high incidence of emotional violence reported as well as an increase in reporting of sexual abuse by the women who accessed counselling services, as seen in Figure 3. Women reported emotional abuse as the highest as their partners and family members realised that physical abuse will be conspicuous and could be immediately used as evidence whereas emotional abuse is insidious and long term where evidence is difficult to find. Women have reported long periods of emotional abuse and ambivalence in relationships.

Figure 3: Forms of violence that clients report facing; n=3460

There has been a steady increase in women identifying and reporting economic abuse. The reporting of economic abuse was seen to be at 11% in 2001, and reached its peak thus far in 2011 at 70.6%. We have seen limited resources, economic constraints and poor earning capacity to be the contributing factors to economic abuse. Women have often reported financial deprivation, no access to resources and not being granted entitlements to property. The reporting of sexual abuse has seen to be steadily increasing from 2008 onwards. The enactment of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act in 2012 (that has made the reporting of sexual abuse of minor girls and boys mandatory), and the Criminal Law (Amendments) Act, 2013 (which was passed in the aftermath of the infamous Delhi rape and murder case of 201225) has led to more identification and reporting of cases of gender-based violence by the service providers. The forms of abuse represented in the figure above are not exclusive of each other as women usually undergo multiple forms of abuse.

Figure 4 shows our work with volunteer women’s groups. What is important to note here is that creating a cadre of volunteers and building their capacity to do active negotiation and strategic resistance against violence is a challenging task. Initially working with many women and forming large number of groups provides a large base of volunteers who can be trained to sustain and carry out the work. An elaborate and extensive programme has to be developed and executed consistently, over a long period of time (at least two years) in order to hold the interest and commitment of the volunteers.

Figure 4: Sanginis engaged in working to end gender-based violence.

Sanginis (members of women’s groups who agree to volunteer with SNEHA) are part of an ‘embodied infrastructure’ of women’s community services and management networks, and become situated in the context of our prevention work.

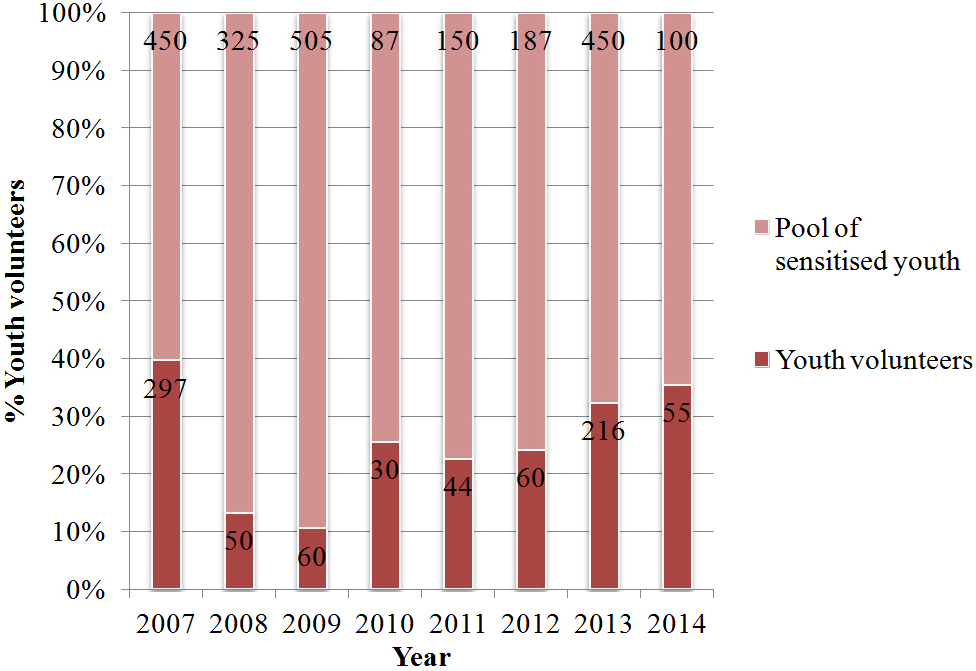

Figure 5 shows that mobilisation of youth has been easier compared to that of Sanginis. On the other hand it has been difficult to sustain their interest and have them consistently volunteer with SNEHA. There was a decline in the number of youth volunteers from 2008 to 2009. This was because we failed to engage them in various activities. We therefore developed strategies to provide creative platforms through SNEHA’s public engagement project, which led to a steady increase in the enrolment of youth volunteers. Our experience shows that young people are receptive to the gender transformative approach.

Figure 5: Youth engaged in addressing gender-based violence.

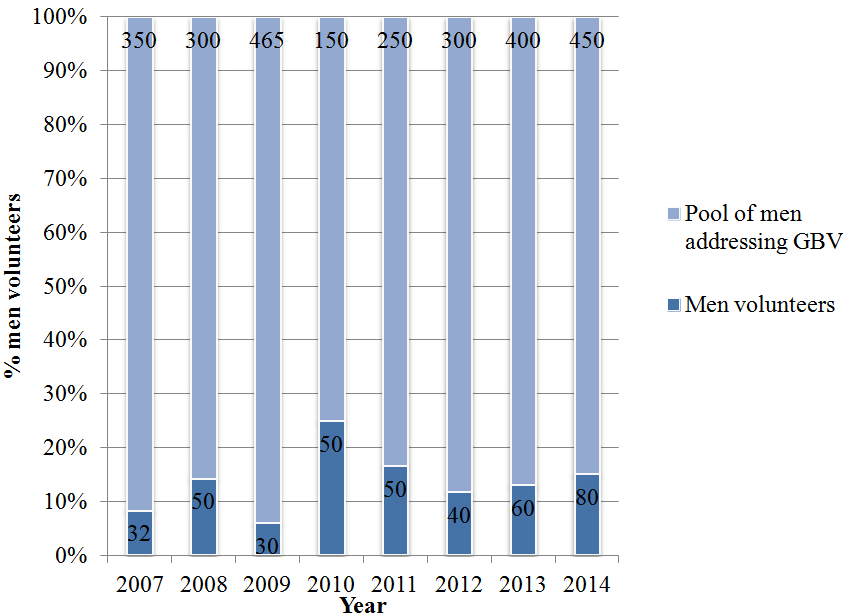

Figure 6 shows engagement of men with the program. Women facing domestic violence are largely unwilling to receive support from men living in the woman’s neighbourhood or community. Their engagement and contribution to the program has been in cases of sexual violence, molestation and child sexual abuse identified from the community.

Figure 6: Men engaged in addressing gender-based violence.

LESSONS LEARNED

The natural evolution of the Program has given us insights into the possibilities of synergising different approaches and the limitations while working with women and communities to prevent gender-based violence. The sensitive nature of the issue poses challenges, such as treading the thin line between an over-assumption of the Program’s authority to intervene in situations and having these situations potentially being misrepresented in the community. Constant support to the community volunteers and being there to facilitate interventions for survivors of violence has helped to build a network of volunteers. Prevention in essence requires service provision and community mobilisation to go hand in hand to bring an increase in reporting of cases. Unlearning and rethinking of deep rooted patriarchal attitudes requires a systematic process of sensitisation. Changing long-held beliefs takes time and happens gradually. It requires helping individuals and communities to create practical alternatives to violence.

We have also realised that the community must be linked to other key players in the gender-based violence arena. The Program therefore evolved a model that encompasses counselling and crisis intervention services, prevention work with communities, reporting via technology, work with systems and advocacy. We use a convergent approach that integrates all these components closely to form a seamless process that benefits the woman. This model on intervention and prevention of violence evolved from our own understanding of successes and failures in exploring different strategies to address gender-based violence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank all the members of local communities who have trusted us enough to allow us into their living spaces. We thank the management and staff members of the public health, law enforcement and judicial systems in Mumbai and Maharashtra state for partnering with SNEHA. We are grateful to the team members of the Program on Prevention of Violence against Women and Children who work on a challenging and complex issue. We thank Vanessa D’Souza and Shanti Pantvaidya for leadership at the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action. We are grateful to the Board of Trustees, senior management and staff of SNEHA. We thank Professor David Osrin of UCL Institute for Global Health for direction. Our evolution and growth as a program was strengthened by numerous collaborators in India and overseas.

CONFLICTSOF INTEREST

None declared.