INTRODUCTION

Vaccination is one of the most effective implements for decreasing the occurrence of infectious diseases. Peptide subunit-based vaccines have many advantages as they are more safe, stable and easy to manufacture compared to the traditional vaccines bearing live attenuated or inactivated pathogens. These modern vaccines contain only the least immunogenic section of an antigen required to elicit the desired immune response.1 However, the use of peptides alone is not sufficient to stimulate the immune system. Therefore, an adjuvant/delivery system is the necessary component to trigger an immune response against the peptide antigen.2

The adaptive immune response generates a long-term pathogen-specific immune response through the generation of a broad amount of different antigen receptors and by the propagation of memory B- and T-cells. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) can kill infected cells by cytotoxic action while the B-cells produce pathogen-specific antibodies. Both of these mechanisms are assisted by T-helper cells. For production of a therapeutic and/or protective immunity, stimulation of CTLs and/or B-cells by vaccination is essential.3,4 Recently, we tested in vivo the ability of peptide-based vaccines including fluorinated lipids in a conjugation with J14 B-cell peptide epitope to produce protective IgG antibodies against J14 antigen.5 It was demonstrated that fluorinated constructs can induce effective humoral immune response once they form nanoparticles. A high antibody titer was produced by fluorinated vaccines, similar to those induced by the positive control (J14 mixed with powerful Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA)) and higher than those produced by non-fluorinated analogues.

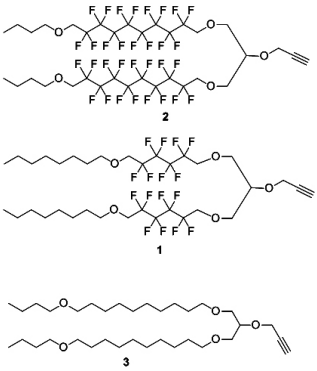

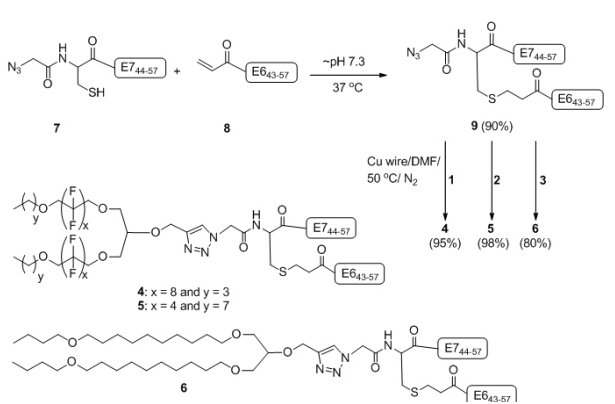

Here, we synthesized two fluorinated lipo-alkynes 1 and 2 and the non-fluorinated analogue 3 as reported previously (Figure 1).5,6 The lipid moieties were conjugated with a peptide epitopes using a copper-catalysed alkyne-azide 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction. The resulting conjugates were assayed in vivo to investigate their ability to elicit cellular immune response in mice.

Figure 1: Fluorinatedlipo-alkynes 1-2 and non-fluorinated lipo-alkyne 3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Copper wire was purchased from Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). HPLC grade acetonitrile was obtained from Labscan (Bangkok, Thailand). All other reagents were obtained at the highest available purity from Sigma-Aldrich (Castle Hill, NSW, Australia). ESI-MS was performed using a Perkin-Elmer-Sciex API 3000 instrument with Analyst 1.4 software (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Toronto, Canada). Analytical RP-HPLC was performed using Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) instrumentation (DGU-20A5, LC-20AB, SIL-20ACHT, SPD-M10AVP) with a 1 mL min−1 flow rate and detection at 214 nm and/or evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD). Separation was achieved using a 0-100% linear gradient of solvent B over 40 min with 0.1% TFA/H2O as solvent A and 90% MeCN/0.1% TFA/H2O as solvent B on either a Vydac analytical C4 column (214TP54; 5 µm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) or a Vydac analytical C18 column (218TP54; 5 µm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm). Preparative RP-HPLC was performed using Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) instrumentation (either LC-20AT, SIL-10A, CBM-20A, SPD-20AV, FRC-10A or LC-20AP x 2, CBM-20A, SPD-20A, FRC-10A) in linear gradient mode using a 5-20 mL/min flow rate with detection at 230 nm. Separations were performed with solvent A and solvent B on a Vydac preparative C18 column (218TP1022; 10 µm, 22 mm × 250 mm), Vydac semi-preparative C18 column (218TP510; 5 µm, 10 mm × 250 mm) or Vydac semi-preparative C4 column (214TP510; 5 µm, 10 mm × 250 mm).

Particle size was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano Series with DTS software with non-invasive backscatter. Multiplicate measurements were performed at 25°C with a scattering angle of 173° using disposable cuvettes and the number-average hydrodynamic particle diameters are reported.

Synthesis of Vaccine Candidate Lipopeptide 4

A mixture of azide derivative 9 (2.6 mg, 0.6 µmol, 1 equiv.) and the lipoalkyne 1 (1.0 mg, 0.9 µmol, 1.5 equivalent) was dissolved in DMF (1 mL), and a copper wire (80 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was degassed for 30 sec by nitrogen bubbling, protected from light with aluminium foil, and stirred at 50 °C under nitrogen. The progress of the reaction was monitored by analytical HPLC (C-4 column) and ESI-MS until the peptide 9 was completely consumed after 5 h. The reaction mixture was purified by using semi-preparative HPLC C-4 column (35-75% solvent B over 60 min). After lyophilisation, the pure lipopeptide 4 was obtained as an amorphous white powder. Compound 4 was analysed by HPLC (C-4 column) t R=27.9 min, purity >97% (detected by UV at 214 nm). Yield: (3.1 mg, 95%). ESI-MS: m/z 1657.9 (calc 1658.3) [M+3H]3+; 1243.8 (calc 1243.7) [M+4H]4+; 995.2 (calc 995.2) [M+5H]5+; MW 4970.8.

Synthesis of Vaccine Candidate Lipopeptide 5

A mixture of azide derivative 9 (3.1 mg, 0.7 µmol, 1 equiv.) and the lipoalkyne 2 (0.9 mg, 1.1 µmol, 1.6 equiv.) was dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) (1 mL) and a copper wire (80 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was degassed for 30 sec by nitrogen bubbling, protected from light with aluminium foil and stirred at 50 °C under nitrogen. The progress of reaction was monitored by analytical HPLC (C-4 column) and ESI-MS until the peptide 9 was completely consumed after 4 h. The reaction mixture was purified by using semi-preparative HPLC C-4 column (35-75% solvent B over 60 min). After lyophilisation, the pure lipopeptide 5 was obtained as an amorphous white powder. Compound 5 was analysed by HPLC (C-4 column) t R=27.4 min, purity >97% (detected by UV at 214 nm). Yield: (3.6 mg, 98%).ESI-MS: m/z 1562.0 (calc 1562.0) [M+3H]3+; 1171.9 (calc 1171.8) [M+4H]4+; 937.7 (calc 937.6) [M+5H]5+; MW 4683.0.

Biological Assay

Mice and cell lines for cellular immunity: Female C57BL/6 (6-8 weeks old) mice were used in this study and purchased from Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Western Australia). TC-1 cells (murine C57BL/6 lung epithelial cells transformed with HPV-16 E6/E7 and ras oncogenes) were obtained from TC Wu.19 TC-1 cells were cultured and maintained at 37 °C/5% CO2 in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% nonessential amino acid (Sigma-Aldrich). The animal experiments were approved by the University of Queensland Animal Ethics committee (DI/034/11/NHMRC) and (UQDI/327/13/ NHMRC) in accordance with National Health and Medical research Council (NHMRC) of Australia guidelines.

In vivo tumor treatment experiments: Five groups of C57BL/6 mice (5 per group) were challenged subcutaneously in the right flank with 1×105 /mouse of TC-1 tumor cells. On the third day after tumor challenge, the mice were injected subcutaneously at the tail base with 100 μg of lipopeptide 4, 5, or 6 in a total volume of 100 μL of sterile-filtered PBS. The positive control received 30 μg of a mixture of E744-57 and E643-57 emulsified in a total volume of 100 μL of Montanide ISA51 (Seppic,France)/ PBS (1:1, v/v). A negative control group wasadministered 100 μL PBS. The mice were given a single immunisation only. The size of the tumor was measured by palpation and calipers every two days and reported as the average tumor size for the group of five mice or as the tumor size for individual mice.20,21

Tumor volume was calculated using the formula V (cm3)=3.14×[largest diameter×(perpendicular diameter)2 ]/6.21 To minimise suffering, the mice were euthanised when the tumor reached 1 cm3 or started bleeding.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Kaplan−Meier survival curves for tumor treatment experiments were applied. Differences in survival treatments were determined using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, difference in tumor sizes were determined using two-way ANOVA; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) oncoproteins E6 and E7 are continuously expressed and are essential for maintaining HPVassociated tumor cell growth. Peptides from the E6 and/or E7 proteins, E643-57 (QLLRREVYDFAFRDL; E643-57)7,8 and E744-57 (QAEPDRAHYNIVTF; E744-57),9 contain CTLs epitopes, and are therefore regularly used for the development of peptidebased vaccines against cervical cancer.6,7,9,10,11,12

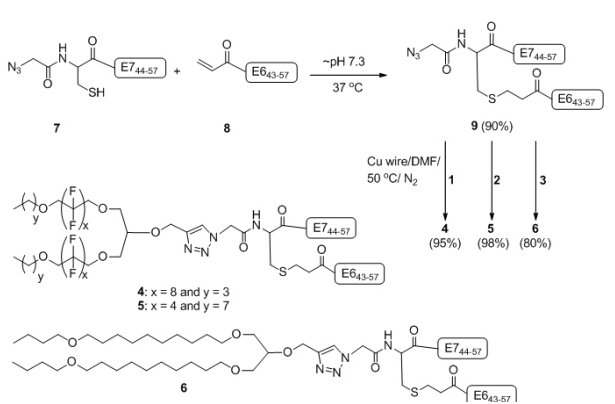

We recently demonstrated that epitopes E643-57 and E744-57 conjugated to lipid 3 can stimulate potent cellular immune response and eradicate tumor in mice without the help of an external adjuvant.6Herein, we conjugated fluorinated analogues ofthis lipid, 1 and 2 (Figure 1) and covalently linked epitopes E643- 57 and E744-57 (9) to produce lipopeptides 4 and 5 (Figure 2). At first, synthesis of E744-57 mercapto-azide (7) and E643-57 acrylate (8) was achieved by Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis (FmocSPPS). A double conjugation strategy6 was used to synthesise lipopeptides 4-6. The first conjugation of the two modified peptides 7 and 8 was accomplished though the Michael-addition mercapto-acrylate reaction to give the E6/E7 azide derivative 9 in 90% yield (Figure 2).6 The final constructs 4-6 were achieved via the second conjugation between the azide derivative 9 and the lipo-alkynes 1-3 under nitrogen atmosphere using the CuAAC reaction in the presence of copper wire13 at 50 °C (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Synthesis of Vaccine Candidates 4-6

Lipopeptides usually have amphiphilic properties and can self-assemble into particles under aqueous conditions.14 Therefore, lipopeptides 4-6 were dissolved/suspended in PBS and vortexed or sonicated to form a homogenous solution. The particle sizes were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) with at least five repetitions. Compound 6 formed 450-750 nm particles while compounds 4 and 5 aggregated toform larger particles with sizes above the detection level of the instrument (>5 µm). The fluorinated compounds 4 and 5 formed milky suspension.

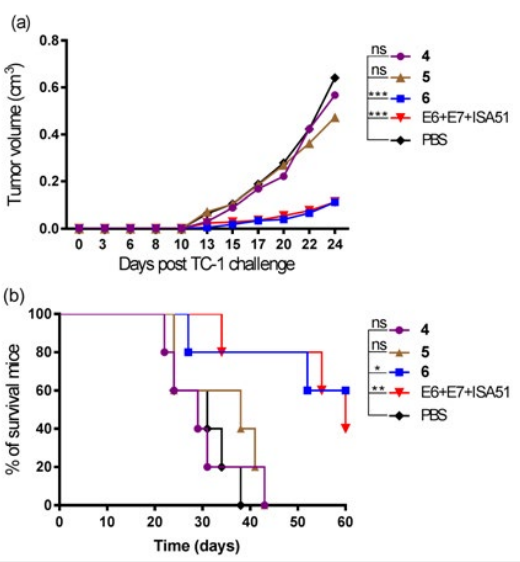

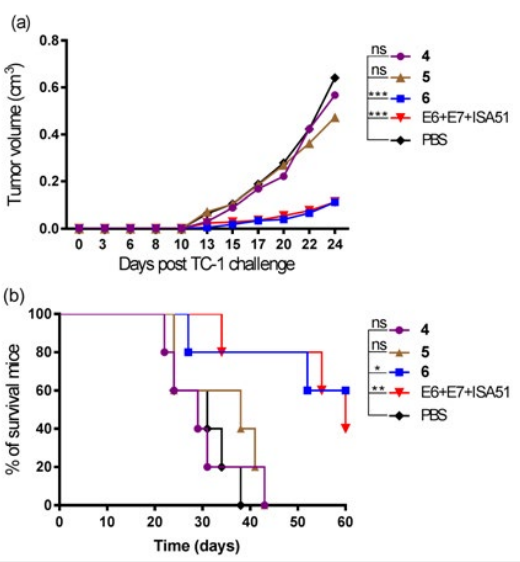

The ability of the fluorinated multi-antigenic conjugates 4-6 to eradicate tumor cells was evaluated in vivo in a C57BL/6 mouse model of HPV-positive tumors. At day zero, mice (5 mice/group) were implanted in the side flank with E6/ E7 positive tumor cells.15 On day three,mice were immunised with either lipopeptide 4, 5, 6, a mixture of E744-57+E643-57 emulsified with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Montanide ISA51) as a positive control, or PBS as a negative control. Unfortunately, persistent tumor growth was observed, thus fluorinated lipopeptides 4 and 5 had a negligible therapeutic effect against the tumor (Figure 3). In contrast, mice immunised with non-fluorinated analogue (6)6 displayed a 60% survival rate (3 out of 5 mice).

Figure 3: In vivo Tumor Treatment Experiments. C57BL/6 (5 per group) were Inoculated Subcutaneously in the Right Flank with 1×105 TC-1 Tumor Cells/Mouse (day 0) and Immunised with Lipopeptides 4, 5, 6, a Mixture of E744-57-E643-57 (1:1) + ISA51 as a Positive Control, or PBS as a Negative Control on day 3. (a) Mean Tumor Volume (cm3 ) in Different Groups of Mice Shown Up to Day 24 after Tumor Implantation (when the First Mouse was Euthanised). The Tumor Volume of each Group was Compared to the Negative Control (PBS) and was Analysed using Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple Comparisons Test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). (b) Survival rate Monitored over 60 days Post-implantation and time to Death plotted on a Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve. Mice were Euthanised when Tumor Volume Reached 1 cm3 or Started Bleeding. The Survival Rate of each Group was Compared to the Negative Control (PBS) and was Analysed using the Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test(*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

The availability of non-toxic and efficient adjuvants that can stimulate cellular and/or humoral immunity without causing side effects is very limited.3 Peptide alone is unable to stimulate the required immune response, thus there is increased demand for the discovery of new molecules that can play this crucial adjuvanting role. Here, we synthesized fluorinated and non-fluorinated

lipopeptides 4-6 (Figure 2). The stimulation of cellular immunity was tested by comparing fluorinated (4-5) and non-fluorinated (6) vaccine candidates that bore two HPV-16 epitopes derived from E6 and E7 (Figure 3). The hydrophobic properties of the two epitopes E643-57 and E744-57 contributed to the formation of big particles of compounds 4-6 in PBS. In addition, fluorine atoms led to a reduction in the solubility of the fluorinated derivatives 4 and 5 and resulted in aggregated particles that were too large to measure by DLS. The non-fluorinated analogue 6 resulted in smaller particles (450-750 nm). The large particle size of fluorinated compounds 4 and 5 (with E6/E7 epitopes ˃5 µm) could be the reason for their poor immunological potency (Figure 3). In large aggregates of 4 and 5, the antigen might be hidden from the immune system. This was supported by recent experiments where aggregated compounds that contained Pam2Cys-E6/E7also (>5 µm) failed to elicit an immune response that stopped tumor growth.6 Similarly, the large microparticles of the poly tert-butyl acrylate-E6/E7 conjugate had a limited efficacy in tumor challenge experiments in mice (10% survival rate) while acrylate conjugates that formed smaller particles were significantly more effective (50% survival rate).16 It was also reported that large particles of ovalbumin loadedbeads failed to induce a strong IFN-γ response, a measure of potent cellular immune activation.17,18The particle size might be the reason why the same fluorinated lipids, when formed small nanoparticles upon conjugation with a highly hydrophilic B-cell epitope, induced a strong humoral response5 ; while when they formed big microparticles in conjugation with the hydrophobic E6/E7 epitopes, they showed a weak cellular response. In our previous work, non-fluorinated analogue 6 was able to produce CD8+ T-cell response6; however, as fluorinated lipopeptides 4 and 5 did not induce promising antitumor immune responses, we did not perform further cellular immunity studies on them. The size of self-assembled fluorinated lipopeptides can be reduced in the future through the introduction of a hydrophilic spacer moiety, such as polyethylene glycol, between fluorinated lipid and peptide epitopes.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PROSPECT

Three multi-antigenic lipopeptide vaccine candidates 4-6 were synthesised using a double conjugation technique. The nonfluorinated multi-antigenic lipopeptide analogue 6 stimulated a robust therapeutic effect against HPV- positive tumors after a single immunisation without the help of an external adjuvant. The fluorinated self-adjuvanting moieties (4 and 5) were not able to eradicate tumor, possibly due to the spontaneous formation of large (>10μm) aggregates in aqueous solution. Therefore further study is required to examine whether it is possible to form small nanoparticles from T-cell epitopes conjugated to fluorinated lipids.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interest.