INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic injury usually presents with constitutional other visceral injuries and isolated traumatic pancreatic injury is relatively uncommon due to its mostly retroperitoneal location. However, pancreatic injury has been reported to be present in 0.2-12% of abdominal trauma cases.1 Approximately two thirds of pancreatic injuries are due to penetrating abdominal trauma and the remaining one thirds is due to blunt trauma. Traumatic pancreatic injury usually occurs in the neck and body region due to presence of vertebrae posteriorly and it ranges from mild contusion/hematoma to severe crushing injury with ductal disruption. Since pancreatic enzymes are alkaline and autolytic in nature, it causes devastating local and systemic complications if expected management is delayed. Pancreatic injury of any grade requires treatment, ranging from conservative management and monitoring to pancreatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure).

CASE SERIES

Case 1

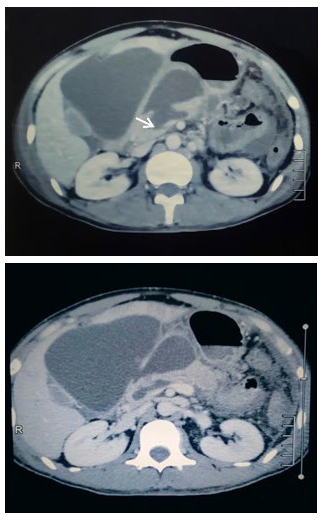

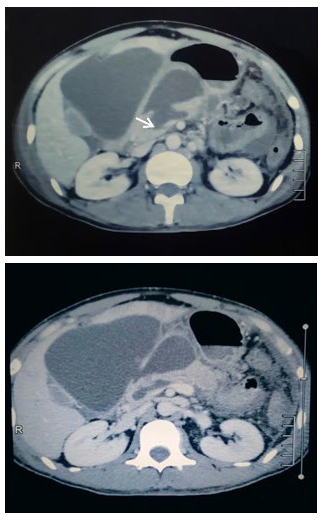

A 30-years-old male with alleged history of physical assault, got beaten up by a group of people with impact over abdomen and right peri-orbital region. He was initially managed at local centre with limited health care facilities. He was referred to our centre after 10-days of trauma with complaints of severe epigastric pain with gradually progressive abdominal distention without vomiting. On examination, his general condition was ill looking with right peri-orbital swelling, raccoon eye and sub-conjunctival hemorrhage. His pulse was 108 beats/min with rest vital signs were stable. On abdominal examination, abdomen was distended with flanks fullness and tenderness over epigastrium on deep palpation. No features of peritonism or other significant findings. On presentation, his investigations were hemoglobin (Hb) 10.9 gm%, total leukocyte count (TLC) 7200, fasting blood sugar 96 mg/dL, urea/creatinine 36/0.9 mg/dL, Na/K 134/4.1 meq/L, serum amylase/lipase 1403/156 U/L, ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis revealed near complete transection of pancreas at neck with large amount of peri-pancreatic fluid collection (Approximately 683 cc). contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen and pelvis revealed pancreatic laceration (1.5 cm×1.5 cm) involving the neck and body region with defect involving the main pancreatic duct opening anteriorly into a large intercommunicating intraperitoneal cystic fluid collection located in the lesser sac, between the stomach and liver and extending into the mesentery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CECT Abdomen and Pelvis Revealed Pancreatic Transection

Patient had persistent abdominal distention, pain and tachycardia with intermittent fever (maximum recorded up to 101 °F), for which ultrasound-guided percutaneous pigtail drainage of peri-pancreatic collection was done. Later, video assisted lavage of the cavity was done through the percutaneous drain site using nephroscope (20 Fr nephroscope with 26 Fr sheath). Findings of scanty necrotic tissues in pseudocyst cavity with healthy granulation tissue noted.

On 2nd day of percutaneous drainage, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was done. Pancreatic ductal disruption was confirmed for which he underwent ERCP guided pancreatic ductal stenting with 7 Fr 10 cm straight stent. His condition improved gradually thereafter and was discharged on 9th day of admission.

Abdominal drain was removed on 18th day of insertion after gradual decrement in drain output.

On 3-months follow-up, he was doing fine. No features of pancreatitis, no peri-pancreatic collection or pancreatic ductal dilatation noted on follow-up scans.

Case 2

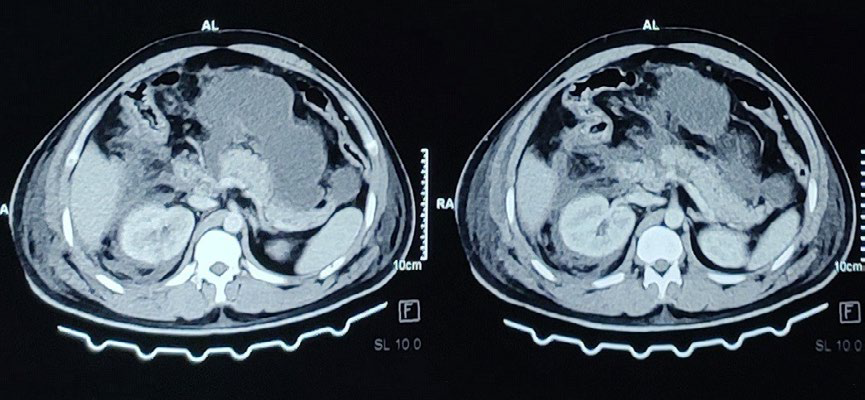

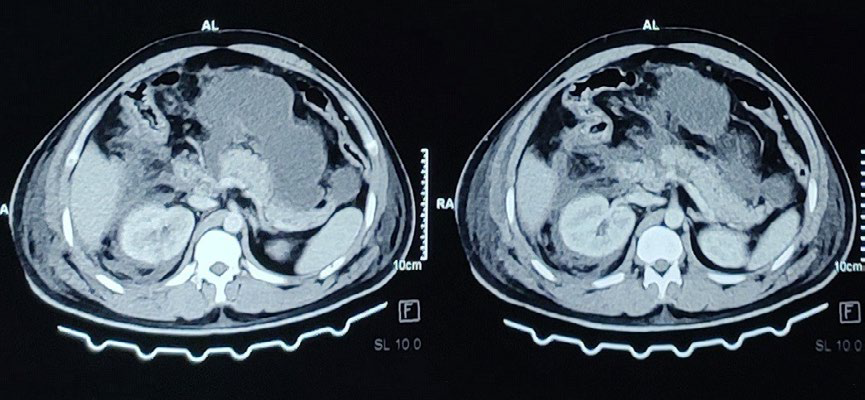

Twenty-eight-years male, alleged history of road traffic accident, sustained injury over upper abdomen with the steering wheel. Presented to the Emergency department within 2-hours of trauma with complaints of upper abdominal pain and abdominal distention. On examination, his glasgow coma scale (GCS) was 15/15 with stable vital parameters. Abdomen was mildly distended with approx. 2×2 cm abrasion over epigastrium with tenderness over upper abdomen. His investigations were Hb 15.6 gm%, TLC 17300, urea/creatinine 31/1.0 mg/dL, Na/K 140/5.6 meq/L, Total/Direct Bilirubin 1.6/0.6 mg/dL, SGPT/SGOT 1550/1263 U/L, ALP 108 U/L, serum amylase/lipase 571/524 U/L, extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST) scan was positive (collection in hepatorenal, perisplenic and pelvic cavity). CECT abdomen and pelvis revealed multiple linear and branching non-enhancing hypodense areas with hyperdense collections in between noted involving segment I, III, IVa and IVb, VII and VIII of liver extending from the hilum to periphery, suggestive of American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale (AAST-OIS) grade IV liver injury; with AAST-OIS grade II right renal injury and also AAST-OIS grade II pancreatic injury (approx 1.8 cm×1 cm sized hypodense non enhancing area noted in the pancreatic head region) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. CECT Abdomen and Pelvis

Patient was initially managed conservatively in the intensive care unit. On 3rd day of trauma, pigtail drainage of abdominal collection through the right subcostal approach was done for persistent abdominal distention, discomfort and persistent tachycardia. Approximately 600 ml of brownish fluid was drained on pigtail insertion and approximately 100-150 ml per day drainage for 3-days thereafter. Drain fluid amylase was 6510 U/L. Daily drain output gradually reduced. On subsequent bedside ultrasound-guided monitoring, another collection in the pelvis was noted and 2nd pigtail drain was placed in the pelvic collection. Approximately 500 ml of brownish colored fluid drained. Patient’s general condition improved gradually over time. Right subcostal drain was removed on 10th day of trauma and pelvic drain on 13th day of trauma. Patient was discharged on the 16th day of trauma/admission.

On follow-up, patient has been doing well, no residual intra-peritoneal collection noted on ultrasound.

DISCUSSION

We have presented 2 cases of pancreatic injury. In the first case, patient had AAST-OIS grade IV pancreatic injury presented to our center after 10-days of trauma, with features of persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). He underwent ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage of pseudocyst followed by video assisted lavage of the cavity through percutaneous drain site using nephroscope (as it has a working channel). Later ERCP confirmed ductal disruption, for which ERCP guided pancreatic duct stenting was done.

Patient was opted for non-operative management solely due to late presentation following trauma and anticipated risks of complications following operative management.

The second case had AAST-OIS grade II pancreatic injury with liver laceration and right renal injury which was managed with serial percutaneous drainage of intra-peritoneal collection.

Both patients doing fine on 3-months follow-up without significant local or systemic complications.

Traumatic pancreatic injury is relatively uncommon, and when present, it is often associated with other visceral injuries (in up to 98% of cases).2,3,4 Overall morbidity rates following pancreatic injury range from 30% to 70% and these are mostly associated with constitutional vascular, hepatico-biliary and bowel injuries.5 Management of pancreatic injury is complex. Ideal treatment for low grade pancreatic injury (grade I and II) is non-operative.6,7 Grade III, IV and V pancreatic injuries require operative interventions due to extensive injury and ductal disruption.6,7 In the past, operative management with exploration was taken as a notion for high grade pancreatic injury with ductal disruption. However, it is not associated with reduced mortality and morbidity. Some selected patients can be safely managed conservatively with minimal invasive techniques without long-term morbidity.8,9

Patient with delayed presentation or missed pancreatic injury usually have high mortality and morbidity.10

In a suspected traumatic pancreatic injury, only clinical and laboratory parameters don’t accurately point to the diagnosis and all cases are to be evaluated as per the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol. Serum amylase/lipase rise only after 6-hours of trauma and their high values do not always confirm the diagnosis of pancreatic injury as it’s raised in other visceral injuries and conditions.11,12

The initial diagnostic modalities in abdominal trauma are ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), but both have low sensitivity for diagnosing pancreatic ductal injury compared to magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or ERCP. CECT abdomen is the imaging modality of choice in a hemodynamically stable patient to detect pancreatic injury, and newer multi-detector CT have nearly 80% sensitivity with high specificity for detecting pancreatic injury. Finding of parenchymal laceration more than 50% in CECT has high likelihood of having pancreatic ductal disruption. However, MRCP has surpassed CT for detection of pancreatic ductal injury.13,14

CONCLUSION

Isolated pancreatic injury is a rare finding in abdominal trauma. Pancreatic injury If present, it occurs with associated other visceral injuries. Treatment of pancreatic injury is complex and ranges from non-operative conservative management to pancreatico-duodenectomy and total pancreatectomy. Early presentation and diagnosis have been associated with lower mortality and morbidity. The old notion of non-operative management for low grade (Grade I and II) and operative management for high grade (Grade III, IV and V) pancreatic injury have changed. Recent trend of minimal invasive techniques of management for selected patients with higher grade pancreatic injury is associated with better outcomes.

CONSENT

The authors have received written informed consent from the patient.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.