1. Ray DC, Schottelkorb A, Tsai MH. Play therapy with children exhibiting symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2007; 16(2): 95-111. doi: 10.1037/1555-6824.16.2.95

2. Sherman J, Rasmussen C, Baydala L. The impact of teacher factors on achievement and behavioral outcomes of children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A review of the literature. Educational Research. 2008; 50(4): 347-360. doi: 10.1080/00131880802499803

3. Saldana L, Neuringer A. Is instrumental variability abnormally high in children exhibiting ADHD and aggressive behavior? Behav Brain Res. 1998; 94(1): 51-59. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00169-1

4. Hanna N. Attention deficit disorder (ADD) attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Is it a product of our modern lifestyles? American Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2009; 6(4).

5. Barzegary L, Zamini S. The effect of play therapy on children with ADHD. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011; 30: 2216-2218. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.432

6. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Moulton JL. Young adult outcome of children with “situational” hyperactivity: A prospective, controlled follow-up study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002; 30(2): 191-198. doi: 10.1023/A:1014761401202

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013: 991.

8. Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006; 11(10): 934-953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869

9. Panksepp J. Play, ADHD, and the construction of the social brain: Should the first class each day be recess? American Journal of Play. 2008; 1(1): 55-79.

10. Curatolo P, Paloscia C, D’Agati E, Moavero R, Pasini A. The neurobiology of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009; 13(4): 299-304. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.06.003

11. Sonnenmoser M. Genetik und Psyche. Bedeutung der Gene nicht überschätzen. Deutsches Ärzteblatt/ PP. 2004: 71-72.

12. Hare B, Tomasello M. One way social intelligence can evolve: The case of domestic dogs. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005; 9: 439-444.

13. Miklósi Á, Topál J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013; 17(6): 287-294. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.04.005

14. Marshall-Pescini S, Viranyi S, Range F. The effect of domestication on inhibitory control: Wolves and dogs compared. PLoS One. 2015; 10(2): e0118469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118469

15. Hejjas K, Vas J, Topál J, et al. Association of polymorphisms in the dopamine D4 receptor gene and the activity-impulsivity endophenotype in dogs. Animal Genetics. 2007; 38(6): 629-633. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01657.x

16. Vas J, Topál J, Péch E, Miklósi Á. Measuring attention deficit and activity in dogs: A new application and validation of a human ADHD questionnaire. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007; 103(1): 105-117. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.03.017

17. Ostrander EA. Both ends of the Leash – The human links to good dogs with bad genes. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367(7): 636-646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204453

18. Kubinyi E, Vas J, Hejjas K, et al. Polymorphism in the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene is associated with activity-impulsivity in German Shepherd Dogs. PLoS One. 2012; 7(1): e30271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030271

19. LaHoste GJ, Swanson J, Wigal SB, et al. Dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphism is associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1996; 1(2): 121-124.

20. Ito H, Inoue-Murayama M, Shimada M. et al. Allele frequency distribution of the canine dopamine receptor D4 gene exon III and I in 23 breeds. J Vet Med Sci. 2004; 66(7): 815-820. doi: 10.1292/jvms.66.815

21. Hejjas K, Kubinyi E, Rónai Z, et al. Molecular and behavioral analysis of the intron 2 repeat polymorphism in the canine dopamine D4 receptor gene. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2009; 8(3): 330-336. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00475.x

22. Hejjas K, Vas J, Kubinyi E, Sasvari-Székely M, Miklósi, Á, Rónai Z. Novel repeat polymorphisms of the dopaminergic neurotransmitter genes among dogs and wolves. Mammalian Genome. 2007; 18(12): 871-879. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9070-0

23. Knowles PA, Conner RL, Panksepp J. Opiate effects on social behavior of juvenile dogs as a function of social deprivation. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1989; 33(3): 533-553. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90382-1

24. Kappeler L, Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and parental effects. Bioessays. 2010; 32(9): 818-827. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000015

25. Kis A, Bence M, Lakatos G, et al. Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with human directed social behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris). PLoS One. 2014; 9(1): e83993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083993

26. Szyf M, McGowan P, Meaney MJ. The social environment and the epigenome. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008; 49(1): 46-60. doi: 10.1002/em.20357

27. Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1998.

28. Harvey ND, Craigon PJ, Blythe SA, England GC, Asher L. Social rearing environment influences dog behavioral development. J Vet Behav. 2016; 16: 13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2016.03.004

29. Bezard E, Dovero S, Belin DD, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Jaber M. Enriched environment confers resistance to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine and cocaine: Involvement of dopamine transporter and trophic factors. J Neurosci. 2003; 23(35): 10999-11007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-10999.2003

30. Gansloßer U, Strodtbeck S. Kastration aus verhaltens biologischer Sicht [In German]. Sitz Platz Fuß. 2011; 2: 52-65.

31. Kaufmann CA, Forndran S, Stauber C, Woerner K, Gansloßer U. The social behavior of neutered male dogs compared to intact dogs (Canis lupus familiaris): Video analyses, questionnaires and case studies. Vet Med Open J. 2017; 2(1): 22-37. doi: 10.17140/VMOJ-2-113

32. Reichler IM. Gesundheitliche Vor- und Nachteile der Kastration von Hündinnen und Rüden [In German]. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde. 2010; 152(6): 267-272.

33. Hense M. Der hyperaktive Hund [In German]. 1st ed. Bernau, Germany: Animal learn Verlag; 2010.

34. Jones AC, Gosling SD. Temparament and personality in dogs (Canis familiaris): A review and evaluation of past research. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2005; 95: 1-53. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.04.008

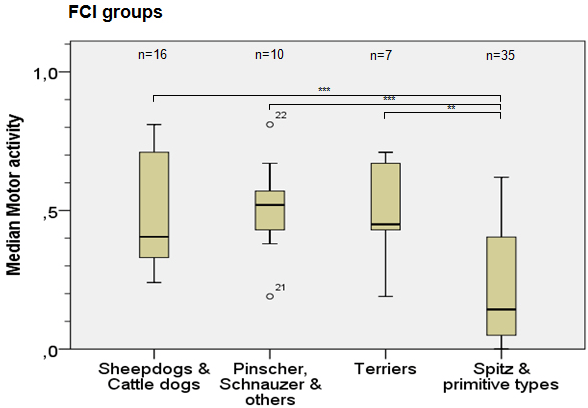

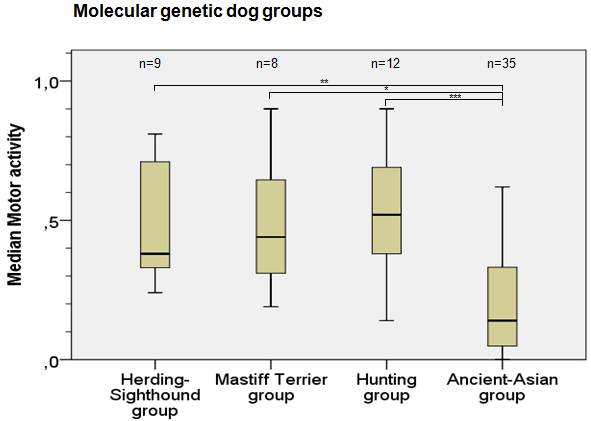

35. Turcsán B, Kubinyi E, Miklósi Á. Trainability and boldness traits differ between dog breed clusters based on conventional breed categories and genetic relatedness. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2011; 132(1): 61-70. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.03.006

36. Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). FCI-Standard Nr. 255 – Akita. Thuin: Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). 2001.

37. Costa PT, Widiger TA. Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. 1994.

38. Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Fédération Cynologique Internationale – For Dogs Worldwide. 2017. Web site. http://www.fci.be/de/Nomenclature/. Accessed March 28, 2017.

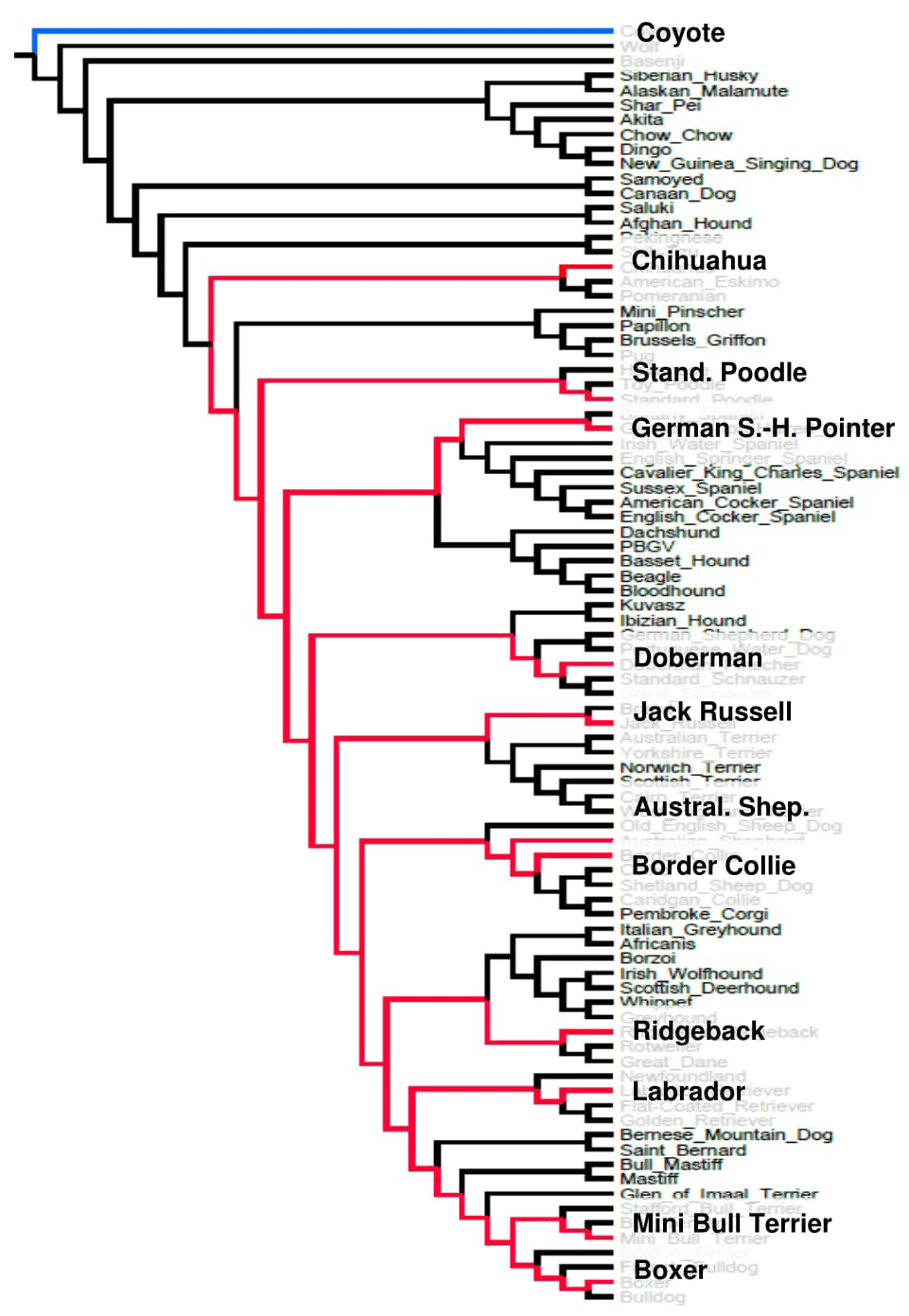

39. Parker HG, Kukekova AV, Akey DT, et al. Breed relationships facilitate fine-mapping studies: A 7.8-kb deletion cosegregates with Collie eye anomaly across multiple dog breeds. Genome Research. 2007; 17(11): 1562-1571. doi: 10.1101/gr.6772807

40. vonHoldt BM, Pollinger JP, Lohmueller KE,et al. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature. 2010; 464(7290): 898-902. doi: 10.1038/nature08837

41. Fritz SA, Purvis A. Selectivity in mammalian extinction risk and threat types: A new measure of phylogenetic signal strength in binary traits. Conservation Biology. 2010; 24(4): 1042-1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01455.x

42. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 2013. Web site. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed April 13, 2017.

43. Panksepp J, Watt D. Why does depression hurt? Ancestral primary-process separation-distress (PANIC/GRIEF) and diminished brain reward (SEEKING) processes in the genesis of depressive affect. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes. 2011; 74(1): 5-13. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2011.74.1.5

44. Beerda B, Schilder MB, Van Hooff JA, de Vries HW, Mol JA. Chronic stress in dogs subjected to social and spatial restriction. I. Behavioral responses. Physiol Behav. 1999; 66(2): 233-242. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00289-3

45. Odendaal JS. Animal-assisted therapy – magic or medicine? J Psychosom Res. 2000; 49(4): 275-280. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00183-5

46. Carter CS. Developmental consequences of oxytocin. Physiol Behav. 2003; 79(3): 383-397. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00151-3

47. Insel TR. Is social attachment an addictive disorder? Physiol Behav. 2003; 79(3): 351-357. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00148-3

48. Insel TR. The neurobiology of affiliation: Implications for autism. In: Davidson RJ, Scherer KR, Goldsmith HH, eds. Handbook of Affective Sciences. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2003: 1010-1020.

49. Strüber N. Die erste Bindung: Wie Eltern die Entwicklung des kindlichen Gehirns prägen. Stuttgart, Germany: Klett-Cotta; 2016.

50. Ma Y, Shamay-Tsoory S, Han S, Zink CF. Oxytocin and social adaptation: Insights from neuroimaging studies of healthy and clinical populations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2016; 20(2): 133-145. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.10.009

51. Panksepp J, Yates G, Ikemoto S, Nelson E. Simple Ethological Models of Depression: Social-Isolation Induced “Despair” in Chicks and Mice. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser-Verlag; doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-6419-0_15

52. Bowlby J. Loss: Sadness and Depression. New York, USA: Basic Books; 1980.

53. Newman JD. The Physiological Control of Mammalian Vocalization. New York, USA: Plenum Press; 1988. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1051-8

54. Panksepp J, Normansell L, Herman B, Bishop P, Crepeau L. Neural and neurochemical control of the separation distress call. In: Newman JD, ed. The Physiological Control of Mammalian Vocalization. New York, USA: Plenum Press. 1988: 263-299. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1051-8_15

55. Hetts S, Clark JD, Calpin JP, Arnold CE, Mateo JM. Influence of housing conditions on beagle behavior. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1992; 34(1-2): 137-155. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80063-2

56. Hubrecht RC, Serpell JA, Poole TB. Correlates of pen size and housing conditions on the behavior of kennelled dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1992; 34(4): 365-383. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80096-6

57. Wells DL, Hepper PG. The influence of environmental change on the behavior of sheltered dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2000; 68(2): 151-162. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00100-3

58. Rütten S, Fleissner G. On the function of the greeting ceremony in social canids–exemplified by African wild dogs Lycaon Pictus. Canid News. 2004; 7.

59. Frank D, Minero M, Cannas S, Palestrini C. Puppy behaviors when left home alone: A pilot study. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007; 104(1): 61-70. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.003

60. Rehn T, Keeling LJ. The effect of time left alone at home on dog welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2011; 129(2): 129-135. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2010.11.015

61. Raineki C, Lucion AB, Weinberg J. Neonatal handling: An overview of the positive and negative effects. Developmental Psychobiology. 2014; 56(8): 1613-1625. doi: 10.1002/dev.21241

62. Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004; 430(7000): 631-639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621

63. Boitani L, Francisci F, Ciucci P, Andreoli G. Population biology and ecology of feral dogs in central Italy. In: Serpell J, ed. The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1995: 217-244.

64. Bloch G. Die Pizza-Hunde. Franckh Kosmos Verlag. 2007.

65. Adams GJ, Johnson KG. Guard dogs: Sleep, work and the behavioral responses to people and other stimuli. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995; 46(1-2): 103-115. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(95)00620-6

66. Majumder SS, Chatterjee A, Bhadra A. A dog’s day with humans – time activity budget of free-ranging dogs in India. Current Science. 2014; 106(6).

67. Burghardt GM. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits. 1st ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Mit Press; 2005.

68. Pellegrini AD. Play as a paradigm case of behavioral Development. Human Development. 2006; 49: 189-192. doi: 10.1159/000091897

69. Salmeri KR, Bloomberg MS, Scruggs SL, Shille V. Gonadectomy in immature dogs: Effects on skeletal, physical, and behavioral development. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991; 198(7): 1193-1203. doi: 10.2460/javma.1991.198.07.1193

70. Farhoody P, Zink C. Behavioral and physical effects of spaying and neutering domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Master Thesis. Hunter College. 2010.

71. Lisberg AE, Snowdon CT. Effects of sex, social status and gonadectomy on countermarking by domestic dogs, Canis familiaris. Animal Behavior. 2011; 81(4): 757-764. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.01.006

72. Zink MC, Farhoody P, Elser SE, Ruffini LD, Gibbons TA, Rieger RH. Evaluation of the risk and age of onset of cancer and behavioral disorders in gonadectomized Vizslas. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014; 244(3): 309-319. doi: 10.2460/javma.244.3.309

73. Niepel G. Kastration Beim Hund [In German]. Stuttgart, Germany: Franckh Kosmos Verlag; 2007.

74. Parker JD, Majeski SA, Collin VT. ADHD symptoms and personality: Relationships with the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004; 36(4): 977-987. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00166-1

75. Nigg JT, John OP, Blaskey LG, et al. Big five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: Links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002; 83(2): 451-469. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.451

76. Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL, USA: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992.

77. Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005; 57: 1313-1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024

78. Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009; 135: 608-637. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024

79. Svartberg K. Breed-typical behavior in dogs — Historical remnants or recent constructs? Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2006; 96(3): 293-313. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.06.014

80. Mahut H. Breed differences in the dog’s emotional behavior. Can J Psychol. 1958; 12: 35-44. doi: 10.1037/h0083722

81. Bradshaw JW, Goodwin D, Lea AM, Whitehead SL. A survey of the behavioral characteristics of pure-bred dogs in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1996; 138(19): 465-468. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.19.465

82. Scott JP, Fuller JL. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Univesity of Chicago Press; 1998.

83. Hart BL. Analysing breed and gender differences in behavior. In: Serpell J, eds. The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1995: 65-67.

84 Ley JM, Bennett PC, Coleman GJ. A refinement and validation of the monash canine personality questionnaire (MCPQ). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009; 116(2): 220-227. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2008.09.009

85. Miklósi Á, Turcsán B, Kubinyi E. The personality of dogs. In: Kaminski J, Marshall-Pescini S. The Social Dog: Behavior and Cognition. Elsevier Inc.; 2014.

86. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987; 51(6): 1173-1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

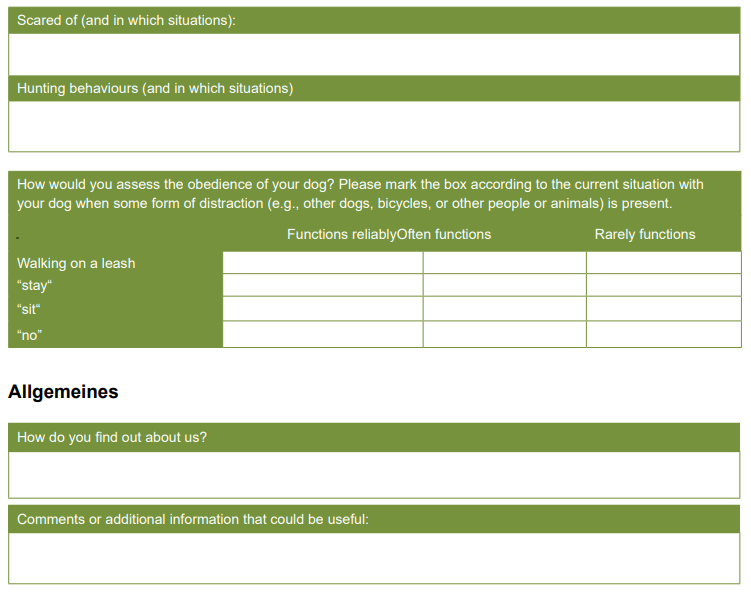

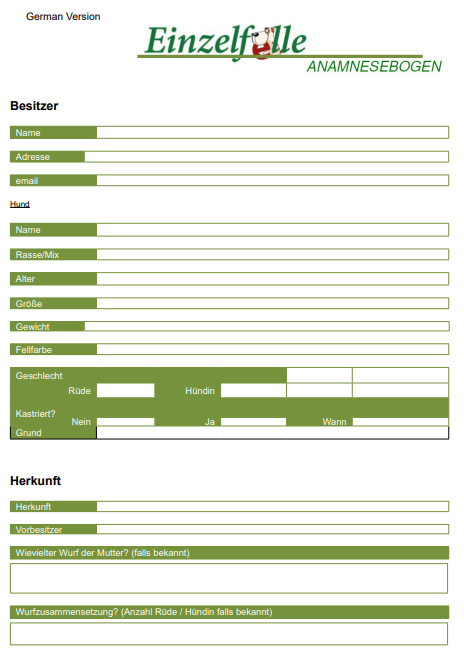

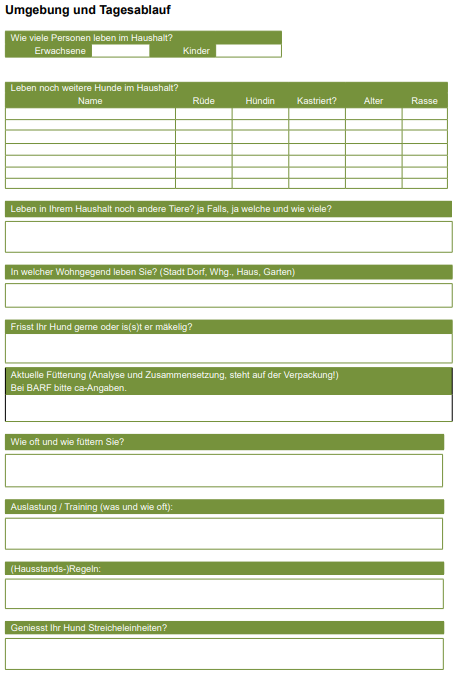

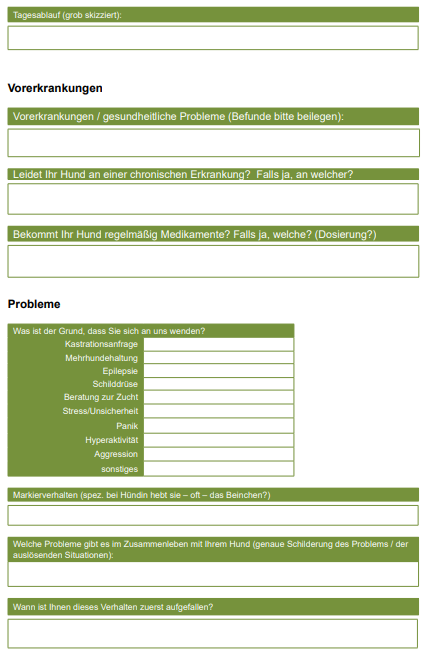

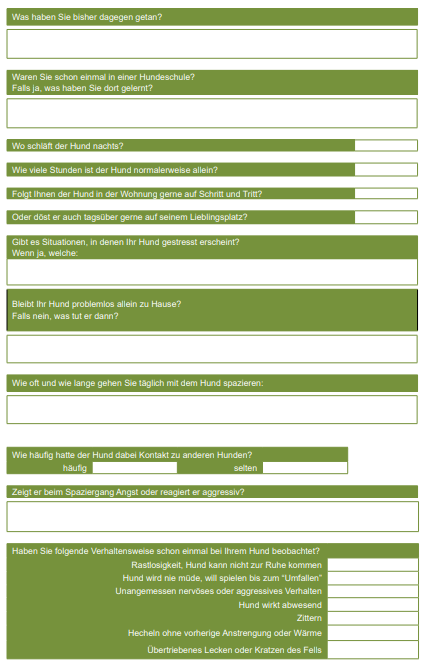

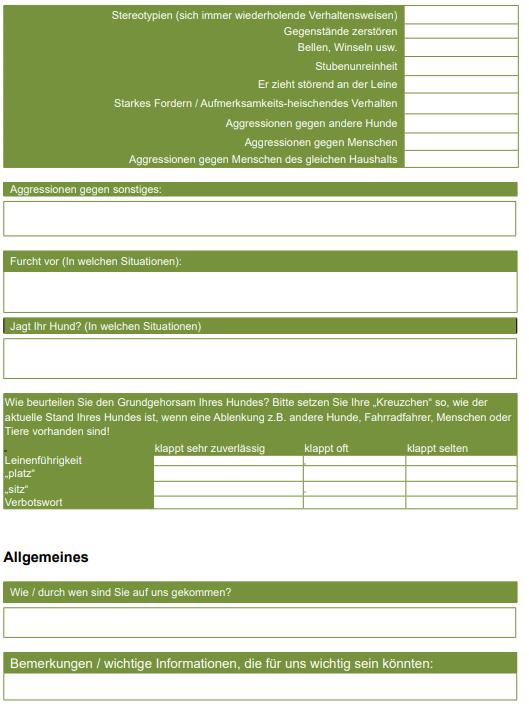

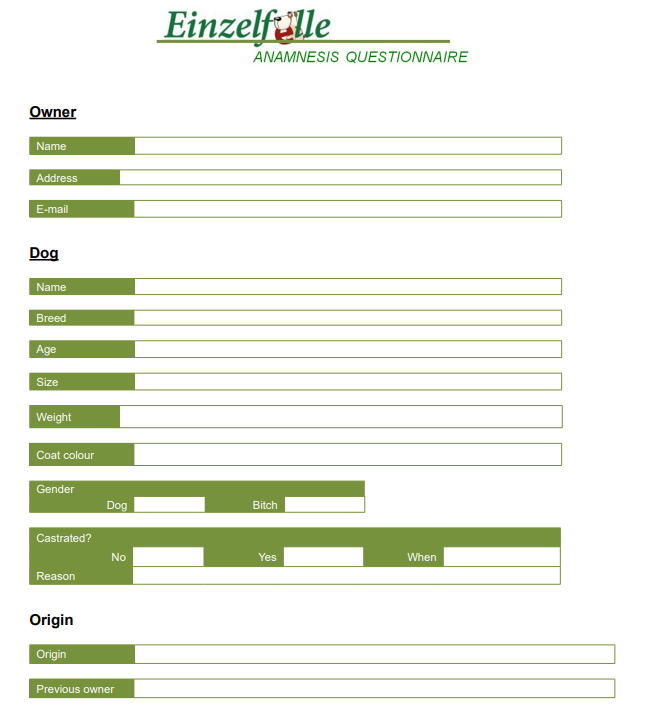

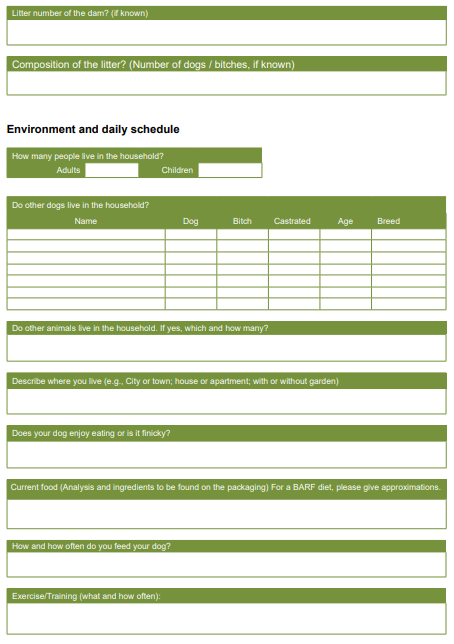

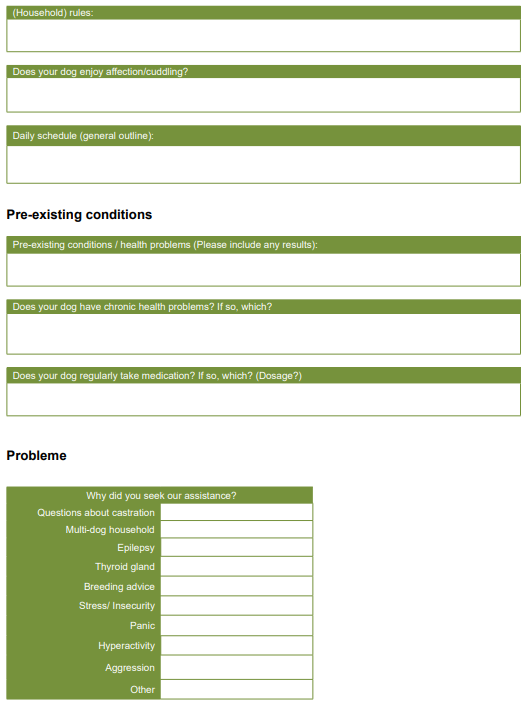

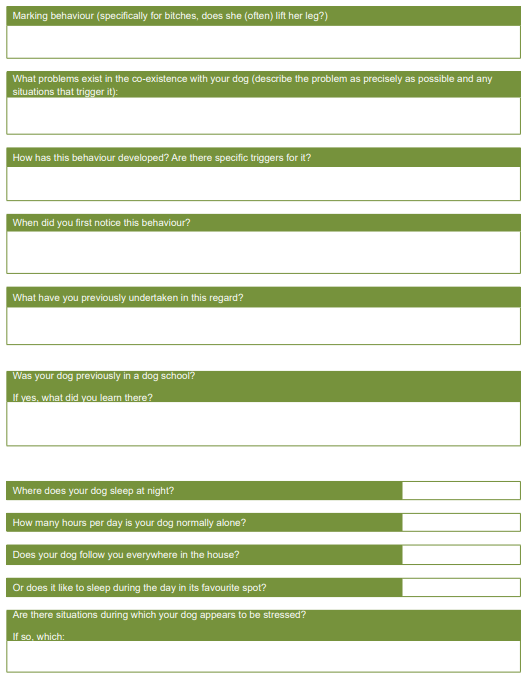

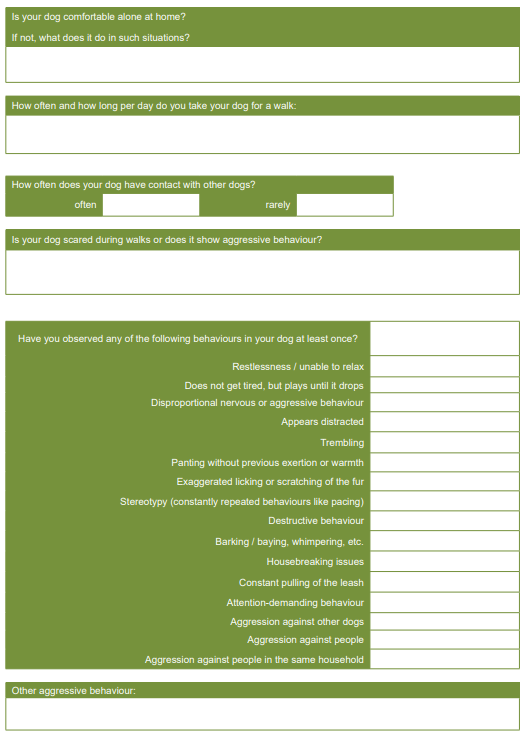

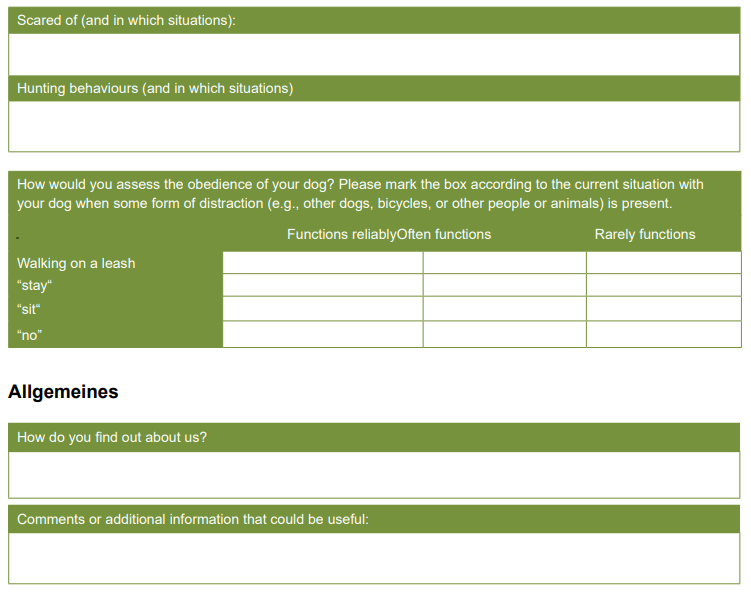

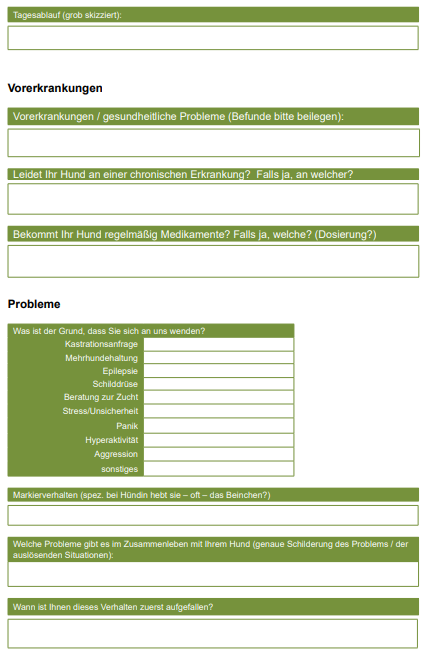

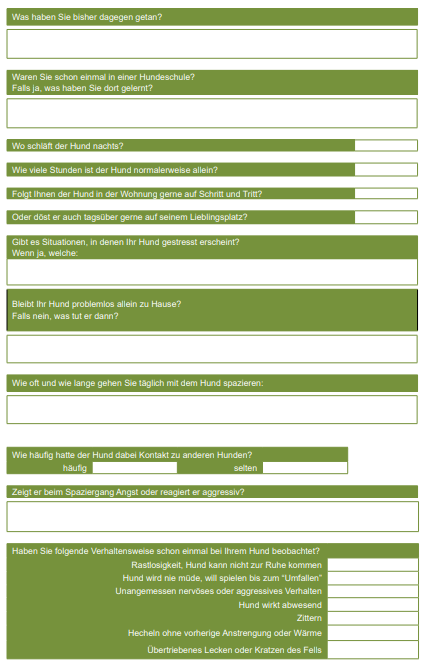

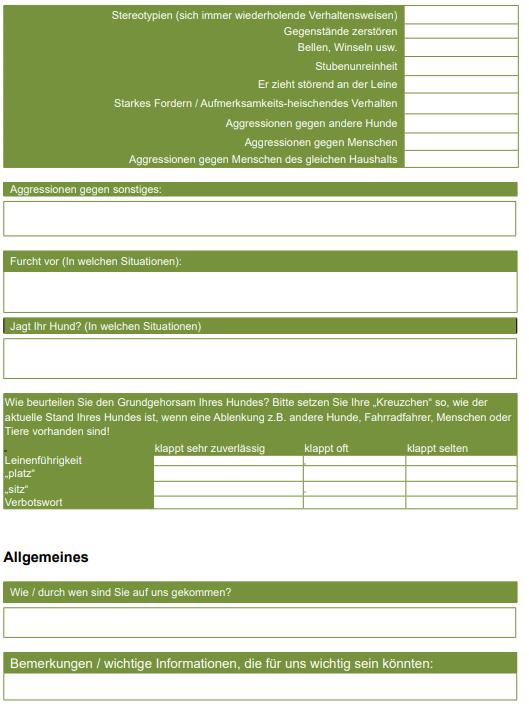

Supplementary Material

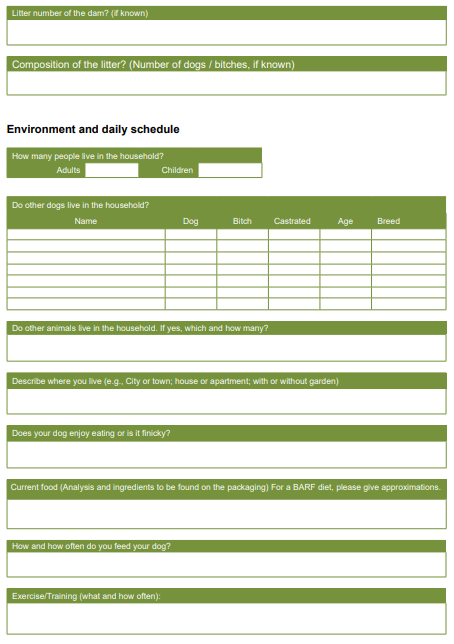

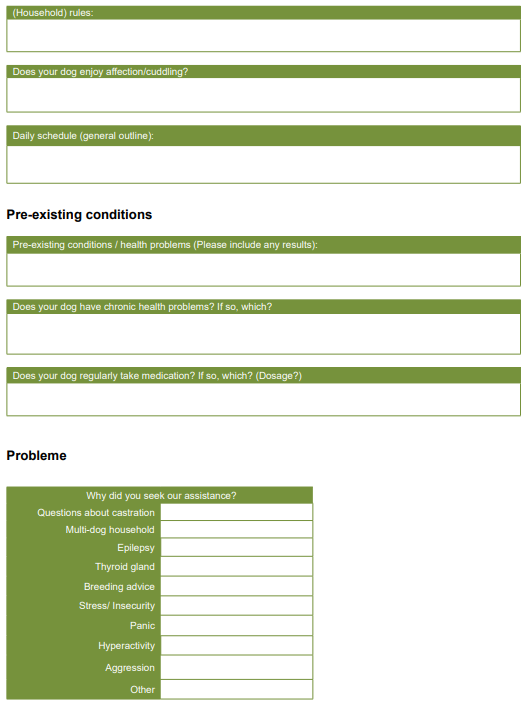

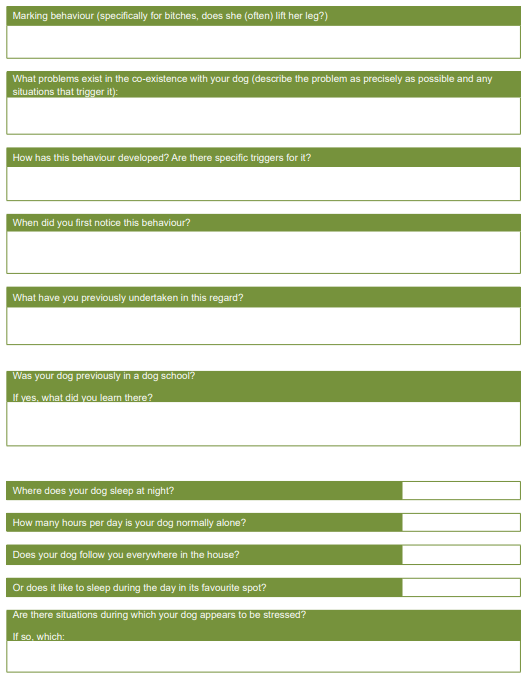

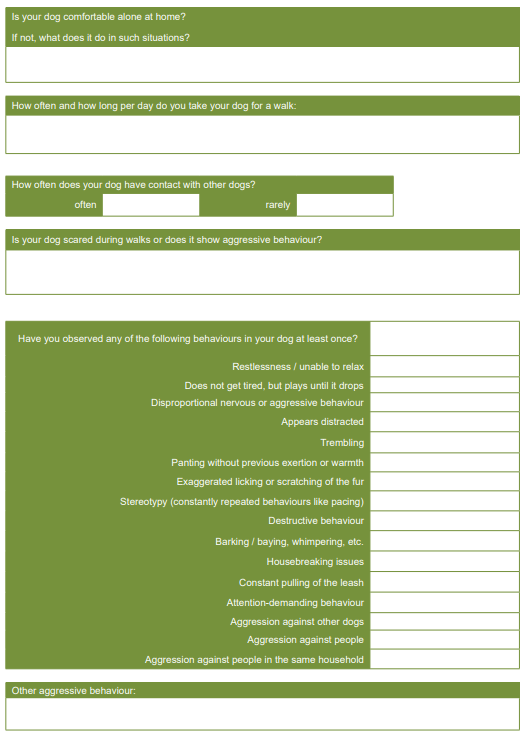

The following shows the questionnaires (English and German versions), which were used for the study (order: ADHD, Anamnesis, Interview and Personality questionnaire).

(English Version)

We will contact you as soon as possible should further questions on our side.

Thank you for your application!

We will process your application as quickly as possible, but please understand that it can take up to a few days until you receive our recommendations because we both are often out of the office.

Interview Questions (English Version)

Introduction

• Where did you get your dog from (Shelter, private breeder, etc.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————–

• How old was your dog when you got it?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1-7 weeks old ( ) 8 – 12 weeks old ( ) >12 weeks old

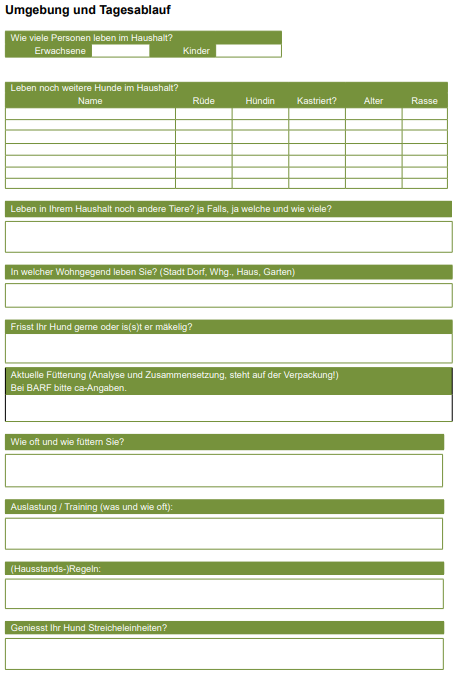

• Where do you live (e.g., city, town, or farm; house or apartment; with or without garden; etc.)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Previous environment and dam-offspring relationship

In the case that you do not have any information in this regard, please continue with the next section.

• What is the litter number of the dam for your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• How large was the litter in which your dog was born (number of puppies)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

• What percentage of the litter of your dog comprised (male) dogs?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-49% ( ) 50-100%

• How old was your dog when it was separated from the dam?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1-7 weeks old ( ) 8 – 12 weeks old ( ) >12 weeks old

• How would you describe the environment in which your dog was born (e.g., problematic or chaotic, quiet, sheltered, etc.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• How many previous owners has your dog had?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• How many opportunities were there for your dog to obtain positive social and physical interactions as a puppy (e.g., interaction with other dogs (through walks or a dog school, among others), playing with the owner(s) or other dogs, meetings with friends and family)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) none ( ) almost none ( ) isolated ( ) some ( ) many ( ) very many

• How often in the first weeks after obtaining your dog / puppy did it receive affectionate behaviour from you?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x/ week( ) 1x/ week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• If daily, how long did the episodes of affectionate behaviour last?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• How often was your dog as a puppy (until six months of age) played outside of a dog school?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How long were the playtimes with the puppy on average for these play days?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-59min ( ) 60-120min ( ) >120min

• How long was your puppy nursed by the dam?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-3 weeks ( ) 4-7 weeks ( ) 8 weeks or more

• How often did the dam show disproportionally aggressive behaviour toward the puppy?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) < 1x/ week ( ) 1x/ week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

Current environment

When you first got your dog:

• How often did it have contact to people that did not belong to your household (friends and other family, etc.)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x/ week ( ) 1x/ week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily ( ) several times daily

• How many other dogs / other pets (e.g., cats) live in your household?

– Other dogs:

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

-Other pets:

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

• What are the other pets (including numbers; e.g., cats: 3x, birds: 2x, etc.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• How often does your puppy have contact to other dogs outside of those in your household or its dog school?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x/ week ( ) 1x/ week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How often does your puppy have contact to other people outside of those in your household or its dog school?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• Do other dogs or animals in your household display disproportionately aggressive behaviour towards your puppy / dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• Do you have (house) rules? Which (e.g., the dog must not lie in the bed, the dog cannot beg, etc.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• How does your dog react to affectionate behaviour?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) aversion ( ) varies ( ) fondly

• How often does your dog receive affectionate behaviour from you?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How long do these episodes last in total?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• Are there problems in the co-existence with your dog (e.g., aggressive behaviour toward strangers, nervous behaviour when alone)?

Please describe these briefly:

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• Do concrete triggers exist for these behaviours (e.g., castration, attacks from other dogs, etc.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• Where does your dog sleep at night?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• How often is your dog alone on average over the day?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-59min ( ) 60-120min ( ) >120min

• Does your dog show problematic behaviours when it is alone(e.g., nervousness, aggression, uncertainty, etc.)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• Are there situations when your dog behaves aggressively?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• Brief description of the situation(s):

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• Are there situations when your dog appears to be stressed?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• Brief description of the situation(s):

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

• Are there situations when your dog appears to be scared?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• Brief description of the situation(s):

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Auslastung Ihres Hundes:

(Training, playtime, walks, dog schools)

• How often do you train your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How many different types of training activity does your dog receive (e.g., obedience training, dexterity training, etc.)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• How often do you play with your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How many different types of playtime activities do you undertake with your dog (e.g., searching for food, romping about, rough and tumble play, locomotor play, etc.)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) >4

• How often do you walk your dog each day??

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) >4

• How long do your daily walks last in total (min / day)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• How often does your dog have contact to other dogs?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• At what age (in years) did your dog first attend dog school?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 to <1 ( ) 1 to <2 ( ) 2 to <3 ( ) 3 or older

• How often do you currently attend dog school with your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How often were you previously with your dog in a dog school (i.e., visits that were set off from current set of visits by a break of a few weeks or more)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• Over what time period did your dog take part in puppy training or young dog training (times can be overlapping)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 to 1 year ( ) 1 to 2 years ( ) >2 years

• How often does / did your puppy take part in puppy training in a dog school?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) <1x / week ( ) 1x / week ( ) several times / week ( ) daily

• How long does / did the puppy training in your dog school last?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• How many playtimes are / were there per puppy training episode of your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• How long is / was a single playtime during the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) a few minutes ( ) 15min ( ) 30min ( ) 45min ( ) 60min ( ) >60min

• How many different types of playtime activities are / were present during the puppy training of your dog (e.g., searching for food, romping about, rough and tumble play, locomotor play, etc.)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1 ( ) 2-3 ( ) 4-5 ( ) >5

• Are / were the playtimes for the puppies interrupted when they became too rough?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) almost never ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) always

• Are / were actions in the puppy training taken to prevent your dog from being bullied by the other dogs?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) almost never ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) always

• How many puppies are / were there in the puppy training of your dog?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 1-5 ( ) 6-10 ( ) 11-15 ( ) 16-20 ( ) >20

• Are / were the puppy training sessions for your dog comprised of the same animals?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• How often do / did new puppies take part in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• Do / did adult dogs also take part in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• How many adult dogs take / took part in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) 7-8 ( ) 9-10 ( ) >10

• How often do / did non-adult dogs take part in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) never ( ) rarely ( ) sometimes ( ) often ( ) very often ( ) always

• What is / was the sex ratio among the puppies in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) single sex only ( ) predominantly one sex ( ) small majority from one sex ( ) balanced

• How large is / was the age difference between the participating puppies in the puppy training?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) a few weeks ( ) a few months ( ) up to ½ year ( ) >½ year

• How large is / was the complete group of participating puppies and their owners (number of puppies + number of people)?

( ) unknown / no answer ( ) 4-6 ( ) 8-10 ( )12-14 ( )16-18 ( ) 20-22 ( ) 24-26 ( ) 28-30 ( ) >30

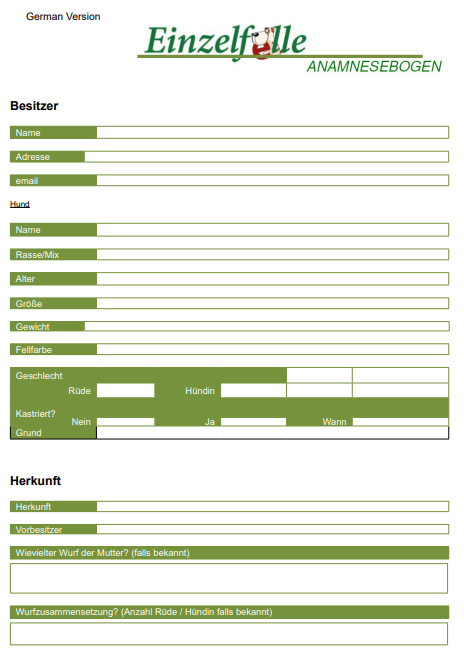

EINZELFELLE (German Version)

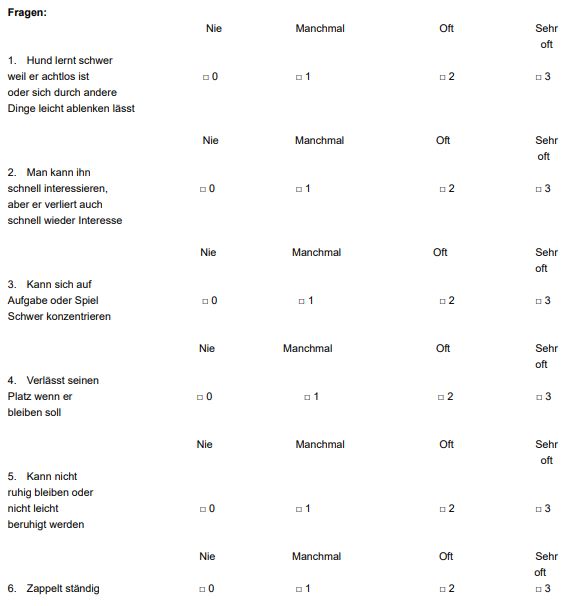

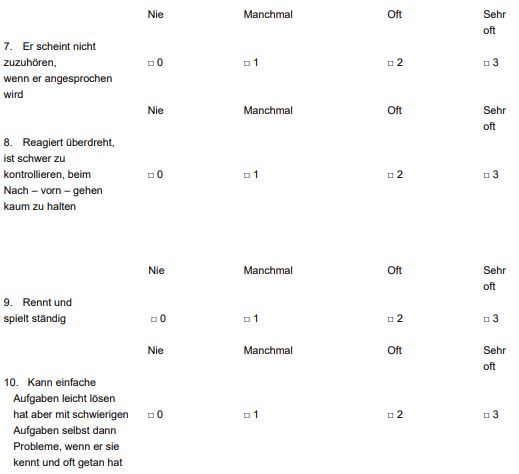

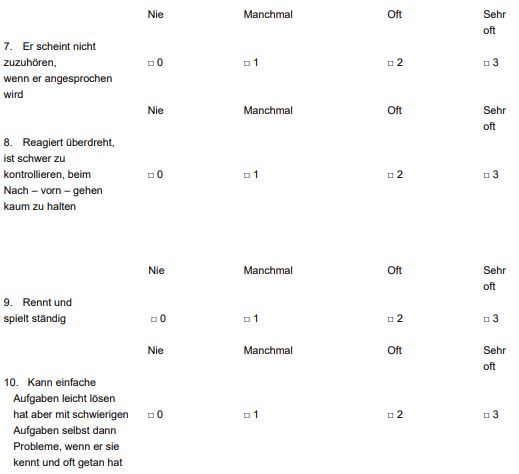

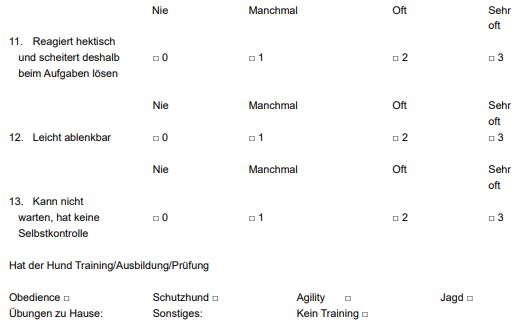

Fragebogen Aufmerksamkeit und Aktivität

Hund (Name / Geschlecht):

Kastriert ja □ nein □

Alter bei Kastration:

Rasse:

Alter/Geburtstag:

Halter:

Name:

Fragen:

Sollten weitere Fragen auftauchen, melden wir uns umgehend.

Vielen Dank für Ihren Auftrag!

Wir werden Ihre Anfrage schnellstmöglich bearbeiten, aber bitte haben Sie Verständnis dafür, dass es einige Tage dauern kann bis unsere Empfehlungen getippt sind, weil wir beide viel unterwegs sind.

Interviewfragen (German Version)

Einführung

• Woher stammt Ihr Hund (Heim, Zucht im privaten Haushalt, usw.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Wie alt war der Hund, als Sie ihn bekamen?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1-7 Wochen ( ) 8 – 12 Wochen ( ) >12 Wochen

• In welcher Wohngegend leben Sie (Stadt, ländlich, Haus, Wohnung, Garten usw.?)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Frühes Umfeld & Mutter-Kind-Beziehung

Falls Sie keine Informationen zu den folgenden Fragen haben, machen Sie bitte mit den Fragen des nächsten „Themenblocks“ weiter.

• Zum wievielten Wurf der Mutter gehörte Ihr Hund?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• Wir groß war der Wurf, aus dem der Welpe stammt (Anzahl der Welpen)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

• Wie hoch war der Anteil der Rüden im Wurf Ihres Hundes?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-49% ( ) 50-100%

• Mit wie viel Wochen wurde der Hund von der Mutter weggegeben?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1-7 Wochen ( ) 8 – 12 Wochen ( ) >12 Wochen

• Wie würden Sie das Umfeld beschreiben, in das der Welpe hineingeboren wurde

(z.B.: problematisches, unruhiges Umfeld; ruhiges Umfeld; behütetes Umfeld o.ä.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Wie viele Vorbesitzer hatte Ihr Hund?

( ) k.A. ( ) keine ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• Gab es Möglichkeiten für den Welpen, positive soziale und physische Erfahrungen zu machen (z.B.: Treffen mit anderen Hunden (Spaziergänge, Hundeschule o.ä.), Spielen mit Besitzern und/oder anderen Hunden, Zusammentreffen von Hund und Bekannten/Freunden der Familie)?

( ) k.A. ( ) gar nicht ( ) fast nicht ( ) vereinzelt ( ) einige ( ) viele ( ) sehr viele

• Wie häufig hat Ihr Welpe/Hund in den ersten Wochen nach der Übernahme Streicheleinheiten von Ihnen bekommen?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche( ) 1x/ Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Falls täglich: Wie lange dauern/dauerten die Streicheleinheiten insgesamt an?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• Wie häufig wurde mit Ihrem Hund im Welpenalter (bis 6 Monate) außerhalb der Welpenstunde gespielt?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/ Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie lang waren hier durchschnittlich die Spieleinheiten mit dem Welpen (an den jeweiligen Spieltagen)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-59min ( ) 60-120min ( ) >120min

• Wie lange wurden die Welpen von der Mutter mit Milch versorgt?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-3 Wochen ( ) 4-7 Wochen ( ) 8 Wochen und mehr

• Zeigte die Mutter im Kontakt mit dem Welpen übermäßige Aggressionen: Falls ja: wie häufig?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) < 1x/Woche ( ) 1x/ Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

Aktuelles Umfeld

Als Sie den Hund bekamen:

• Wie häufig hatte er von Beginn an Kontakt zu Personen, die nicht aus Ihrem Haushalt stammen (Freunde, Bekannte, usw.)?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche( ) 1x/ Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich ( ) mehrmals täglich

• Wie viele andere Hunde/Haustiere (Bsp.: Katzen) leben noch in Ihrem Haushalt?

Andere Hunde:

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

• Sonstige Haustiere:

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) >6

• Welcher Art sind die anderen Haustiere (mit Angabe zur Anzahl, z.B.: Katzen: 3x, Vögel: 2x, usw.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Wie häufig hat der Welpe Kontakt zu anderen Hunden, die nicht aus Ihrem Haushalt oder aus der Hundeschule stammen?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/ Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie häufig hat der Welpe Kontakt zu anderen Menschen, die nicht aus Ihrem Haushalt oder aus der Hundeschule stammen?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/ Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Zeigen andere Hunde bzw. Tiere Ihres Haushalts übermäßige Aggressionen gegenüber Ihrem hier vorgestellten Welpen/Hund?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche( ) 1x/ Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Haben Sie (Haus-) Regeln? Welche sind das (z.B.: Hund darf nicht ins Bett, Hund darf nicht betteln usw.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Wie reagiert Ihr Hund auf Streicheleinheiten?

( ) k.A. ( ) Abneigung ( ) Verschieden ( ) Zuneigung

• Wie oft bekommt Ihr Hund aktuell von Ihnen Streicheleinheiten?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche( ) 1x/ Woche ( ) mehrmals/ Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie lange dauern die Streicheleinheiten insgesamt?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• Gibt es Probleme im Zusammenleben mit Ihrem Hund (z.B.: aggressives Verhalten gegenüber Fremden, nervöses Verhalten bei Alleinsein)? Bitte beschreiben Sie dies kurz:

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Gab es konkrete Schlüsselauslöser für genannte Verhaltensweisen

(z.B.: Kastration, Angriffe durch andere Hunde o.ä.)?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Wo schläft der Hund nachts?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Über welchen durchschnittlichen Zeitraum täglich ist der Hund allein?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-59min ( ) 60-120min ( ) >120min

• Zeigt der Hund ein Problemverhalten, wenn er alleine ist

(z.B.: nervöses Verhalten, aggressives Verhalten, unsicheres Verhalten o.ä.)?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Gibt es Situationen, in denen Ihr Hund aggressiv reagiert?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Kurze Beschreibung der Situationen:

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Gibt es Situationen, in denen Ihr Hund gestresst reagiert?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Kurze Beschreibung der Situationen:

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

• Gibt es Situationen, in denen Ihr Hund sich fürchtet?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Kurze Beschreibung der Situationen:

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Auslastung Ihres Hundes

(Trainings, Spiele, Spaziergänge, Erfahrungen durch Hundeschule und Welpenstunden)

• Wie häufig trainieren Sie mit Ihrem Hund?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/Woche ( ) täglich

• An wie vielen verschiedenen Arten von Trainings nimmt Ihr Hund teil

(z.B.: Gehorsamkeitsübungen, Geschicklichkeitsübungen o. ä.)?

( ) k.A. ( ) keine ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• Wie häufig spielen Sie mit Ihrem Hund?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie viele verschiedene Arten von Spielen Sie mit Ihrem Hund

(z.B.: Futtersuchspiele, Freies Toben, Beweglichkeitsspiele o. ä.)?

( ) k.A. ( ) keine ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) >4

• Wie häufig gehen Sie mit Ihrem Hund am Tag spazieren?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) >4

• Wie lange dauern die Spaziergänge insgesamt pro Tag (Min./Tag)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0-29min ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• Wie häufig hat der Hund dabei Kontakt zu anderen Hunden?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Ab welchem Alter (in Jahren) nahm der Hund an der Hundeschule teil?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 bis kleiner 1 ( ) 1 bis kleiner 2 ( ) 2 bis kleiner 3 ( ) 3 und älter

• Wie oft sind Sie aktuell mit Ihrem Hund in der Hundeschule?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie oft waren Sie früher mit Ihrem Hund in der Hundeschule (Hundeschulbesuche vor aktuellem Besuch einer Hundeschule, mit Abstand von mind. ein paar Wochen Pause dazwischen)?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/Woche ( ) täglich

• Über welchen Zeitraum war Ihr Hund in Welpenstunden bzw. Junghundegruppen in etwa eingebunden (kann beides in einander übergehen)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 0 bis weniger als 1 Jahr ( ) 1 bis 2 Jahre ( ) >2 Jahre

• Wie häufig nimmt/nahm Ihr Welpe an Welpenstunden teil?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) <1x/Woche ( ) 1x/Woche ( ) mehrmals/Woche ( ) täglich

• Wie lange dauert/ dauerte eine Welpenstunde in Ihrer Hundeschule in etwa?

( ) k.A. ( ) 30-60min ( ) 61-90min ( ) 91-120min ( ) >120min

• Wie hoch ist/war die Anzahl an Spieleinheiten pro Welpenstunde Ihres Hundes?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1 ( ) 2 ( ) 3 ( ) 4 ( ) 5 ( ) >5

• Wie lange dauert/dauerte eine Spieleinheit in der Welpenstunde im Schnitt in etwa?

( ) k.A. ( ) wenige Minuten ( ) 15min ( ) 30min ( ) 45min ( ) 60min ( ) >60min

• Wie viele unterschiedliche Arten von Spielen gibt/gab es in der Welpenstunde Ihres Hundes (z.B.: Futtersuchspiele, Freies Toben, Geschicklichkeitsspiele o.ä.)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1 ( ) 2-3 ( ) 4-5 ( ) >5

• Werden/wurden die Spiele zwischen den Welpen abgebrochen, wenn zu ruppig gespielt wird/wurde?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) fast nie ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) immer

• Wird/wurde in den Welpenstunden verhindert, dass Ihr Hund von anderen Hunden gemobbt wurde?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) fast nie ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) immer

• Wie viele Welpen befinden/befanden sich in der Welpenstunde Ihres Hundes?

( ) k.A. ( ) 1-5 ( ) 6-10 ( ) 11-15 ( ) 16-20 ( ) >20

• Setzen sich die Welpenstunden jedes Mal aus den gleichen Hunden zusammen?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Wie häufig nehmen/nahmen neue Welpen an den Welpenstunden teil?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Sind/waren auch erwachsene Hunde in den Welpenstunden dabei?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Wie viel erwachsene Hunde sind/waren im Schnitt in den Welpenstunden dabei?

( ) k.A. ( ) keine ( ) 1-2 ( ) 3-4 ( ) 5-6 ( ) 7-8 ( ) 9-10 ( ) >10

• Wie häufig nehmen nicht-erwachsene Hundehalter an den Welpenstunden teil?

( ) k.A. ( ) nie ( ) selten ( ) manchmal ( ) häufig ( ) sehr häufig ( ) immer

• Wie ist/war in etwa die Geschlechterverteilung der Welpen in den Welpenstunden?

( ) k.A. ( ) nur ein Geschlecht ( ) überwiegend ein Geschlecht ( ) leichte Mehrheit eines Geschlechts ( ) ausgeglichen

• Wie groß sind/waren die Altersunterschiede der teilnehmenden Welpen in etwa maximal?

( ) k.A. ( ) wenige Wochen ( ) wenige Monate ( ) bis ½ Jahr ( ) >½ Jahr

• Wie groß ist/war in der Regel die Gruppe aus teilnehmenden Welpen und ihren Besitzern (Anzahl Hundeteilnehmer + Anzahl Personen)?

( ) k.A. ( ) 4-6 ( ) 8-10 ( )12-14 ( )16-18 ( ) 20-22 ( ) 24-26 ( ) 28-30 ( ) >30

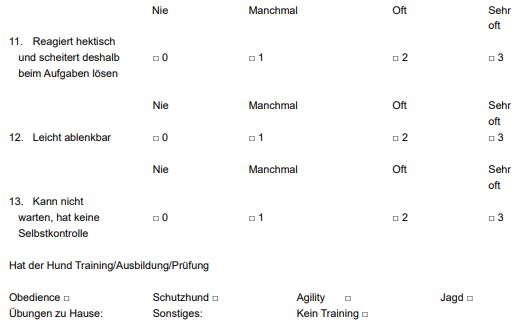

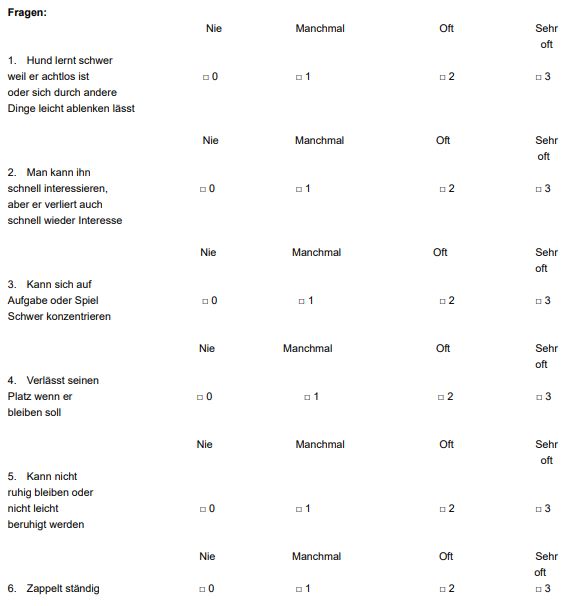

Mein Hund…

1. … wirkt manchmal deprimiert und niedergeschlagen. (E, 4)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

2. … ist eher zurückhaltend und reserviert, wenn eine fremde Person in unsere Wohnung kommt. (E, 6)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

3. … lässt sich auch in turbulenten Situationen nicht aus der Ruhe bringen. (Ä, 9)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

4. … steckt voller Energie und Tatendrang. (A, 11)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

5. … ist oft in Streitereien mit anderen Artgenossen verwickelt (G, 12).

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

6. … reagiert leicht angespannt. (Ä, 14)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

7. … ist begeisterungsfähig und animiert andere Hunde zum Spielen. (G, 16)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

8. … ist überhaupt nicht nachtragend, geht immer wieder unvoreingenommen auf Menschen zu. (G, 17)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

9. … ist eher der stille Typ, hält sich im Kontakt zurück. (E, 21)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

10. … ist anderen Hunden gegenüber eher Misstrauisch. (Ä, 22)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

11. … ist leicht für neue Spielideen zu begeistern. (A, neu)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

12. … ist emotional ausgeglichen und nicht leicht aus der Fassung zu bringen. (Ä, 24)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

13. … ist durchsetzungsfähig und energisch. (E, 26)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

14. … kann sich kalt und distanziert verhalten. (G, 27)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

15. … ist erfinderisch und einfallsreich, wenn es darum geht verstecktes Futter oder Spielzeug zu finden oder zu erreichen. (A, 25)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

16. … wirkt manchmal schüchtern und gehemmt. (E, 31)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

17. … bleibt selbst in Stresssituationen ruhig und gelassen. (Ä, 34)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

18. … versteht in Spielsituationen oft nicht, was von ihm verlangt wird. (A, neu)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

19. … kann sich schroff u. abweisend anderen Hunden gegenüber verhalten. (G, 37)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

20. … wird leicht nervös und unsicher. (Ä, 39)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

21. … hat außer Fressen und schlafen nicht viele Interessen. (A, 10)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

22. … ist sehr selbstbewusst. (E, 45)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

23. … hat oft Streit mit anderen Hunden. (G, 48)

n trifft zu (0) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (2)

24. … hat eine gute Auffassungsgabe und lernt schnell. (A, neu)

n trifft zu (2) n trifft zum Teil zu (1) n trifft nicht zu (0)

HUNDNAME und RASSE: …………………………………………………………….

The references concerning i) the ADHD and ii) the personality questionnaire:

i. Vas J, Topál J, Péch E, Miklósi Á. Measuring attention deficit and activity in dogs: A new application and validation of a human ADHD questionnaire. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007; 103(1): 105-117. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.03.017

ii. Turcsán B, Kubinyi E, Miklósi Á. Trainability and boldness traits differ between dog breed clusters based on conventional breed categories and genetic relatedness. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2011; 132(1): 61-70. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.03.006