INTRODUCTION

With a population of 1.4 million people, the Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated areas in the world with 3800 inhabitants/km² and a population growth of 4% per year. Seventy-eight percent of the population within Gaza are refugees and over half of the one million registered refugees are crammed into eight refugee camps managed by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA).1 Eighty percent of the population in Gaza falls below the poverty line, with an income of US$ 2 per day (up from 30% in 2000) and the unemployment level stands at approximately 50%. In addition, people in Gaza have been subjected to military occupation, causing significant psychological trauma, particularly for children.2 In Rafah, the situation is particularly acute. According to the ministry of social affairs, 25% of all the people killed in Rafah were children, and one in four children have been injured. The decline in the well-being and quality of life of children in Gaza over the past 2 years has been rapid and profound.3

Since the beginning of 2006, the situation has become more uncertain and can only be viewed with concern by the international organizations working in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Specifically, this uncertainty is based on the results of the Palestinian Legislative Council elections at the end of January 2006 in which the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) won 74 of the 132 seats. Following this election, the International community, through public statements issued by the Quartet for the Gaza disengagement, the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) have asked the future Hamas-led government to commit to non-violence, to the recognition and to the acceptance of previous obligations (the Roadmap) in order to allow international donors to continue providing funds to the PA. Israel has announced that it will withhold monthly tax payments to the PA, amounting to between US$ 50 million and US$ 65 million per month and constituting about two-thirds of the income derived from Palestinian economic activity.4

Trauma and Violence

Numerous studies have directly linked post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among children to the violence and mobility restrictions experienced on a daily basis, including the death and injury of family and friends, damage to property, and the frustration and poverty they sustain through closures, curfews and home confinement. Children have witnessed loved ones being killed or injured; have spent childhood years searching for their belongings in the rubble of destroyed homes and schools, and are living in the reality that no place is a safe place.5

Previous studies with children and adolescents exposed to political violence and armed conflict have predominantly focused on the impact of trauma on their mental health.6 It is well established that exposure to political violence is positively correlated with mental health presentations (usually post-traumatic stress disorders and depression), often in a ‘dose-effect’ relationship. The underlying mechanisms have been more difficult to explore, because of the number of potentially confounding variables such as loss of loved ones, disruption of social networks, lack of basic health needs, or displacement. It is well established that exposure to political violence is positively correlated with mental health presentations (usually post-traumatic stress disorders and depression), often in a ‘dose-effect’ relationship.7,8,9,10,11

Following the war in former Yugoslavia, the risk factors for post-traumatic and depressive disorders in children and young people were investigated and different patterns for the two types of psychopathologies were analyzed. Variance in post-traumatic stress symptoms was mainly explained by traumatic war experiences (20%) and individual and socioeconomic factors (17%), and less (9%) by cognitive appraisals and coping mechanisms. In contrast, depression was predicted by individual and socioeconomic factors (36%) and less by war experiences (8%), whilst cognitive appraisal and coping mechanisms did not contribute significantly.12 Family adaptation to the Lebanese war was predicted by family resources and social support, and was associated with increased use of cognitive coping strategies. Also, perceived stress was a stronger predictor than the actual events experienced by families.13

Different models and frameworks have been proposed and investigated and coping strategies adopted by young people in response to stressful events such as trauma. By using various coping strategies, individuals try to modify adverse aspects of their environment as well as to minimize internal threat induced by stress, in a dynamic and reciprocal relationship between emotions and coping.14,15 Coping strategies have been broadly defined as problem-focused (acting on the environment or the individual) or emotion-focused (attempting to change the meaning of the event or how this is attended to.16 They are often also classified as either primary (the judgment of an encounter as stressful) or secondary appraisal (evaluation of the potential effectiveness and consequences of using coping strategies).17 Most research in young life arises from adolescents and young adults who suffered chronic illness, abuse-related trauma, or who have experienced other types of stressful events.18 In recent years, there has also been increasing attention on the impact of war, trauma and political conflict on young people and their families, and the underlying mechanisms involved.

It is important to note that not all coping responses are specific to the conflict, as these can be interlinked with universal adolescent developmental issues. For example, some concerns expressed by high school students in Jerusalem were specific to the conflict in the region, i.e., coping with aggression, war, and enlistment into the army, while other concerns were universal (self-image, peer relationships, and school).19

The aims of this study were (1) To explore the consequences of trauma, in particular the extent to which children suffering from a range of behavioural and emotional disorders becomes the primary driver of violence at the individual, family and community level, (2) To find out the types of coping strategies used by children to overcome the consequences of trauma, (3) To explore the relationship between trauma, PTSD, mental health problems, and coping strategies.

METHOD

Participants

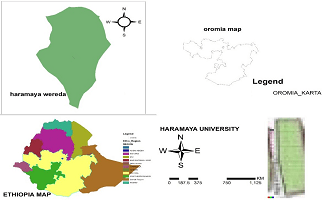

The population of this study includes a random sample of children attending governmental and UNRWA schools. According to literature, a sample of 5-7% of the population is representative of the population. From a total of 55,762 students enrolled in schools in the south of Gaza Strip (Rafah area), 6% of the total number of children i.e., 317 students were selected. Children aged between 9-16 years were included and the numbers of children were divided according to the percentage of children attending different schools.

MEASURES

Sociodemographic Characteristic Questionnaire

This questionnaire includes sex, age, place of residence, and family income.

Gaza Traumatic Events Checklist for Political Violence20

This checklist consists of 28 items covering different types of traumatic events that a child may have been exposed to in the particular circumstances of regional conflict and political violence. This checklist covered three domains of trauma. The first domain covers witnessing the acts of violence such as witnessing killing of relatives, witnessing home demolition, bombardment, and injury of others. The second domain covers the hearing experiences such as hearing killing or injury of friends or relatives. While the third domain covers personal traumatic events such as being shot, injured, or beaten. This checklist can be completed by children of the age group 9-16 years (‘yes’ or ‘no’).

Child Post Traumatic Stress Reaction Index21

This scale is a standardized 20-item self-report measure designed to assess post-traumatic stress reactions of children of 6-16 years following exposure to a broad range of traumatic events. It includes three subscales, intrusion (7 items), avoidance (5 items) and arousal (5 items), and three additional items. The scale has been found to be valid in detecting the likelihood of PTSD.

Items are rated on a 0-4 scale, and the range of total Child Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (CPTSD-RI) scores is between 0-80. Scores are classified as ‘mild PTSD reaction’ (total score 12-24), ‘moderate’ (25-39), ‘severe’ (40-59), and ‘very severe reaction’ (above 60). The CPTSD-RI used in this study was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-IIIR) criteria, rather than using another PTSD instrument based on DSM-IV criteria, as the CPTSD-RI had already been validated in the Arab culture.22

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire23

The questionnaire is one of the most commonly used scales in the assessment of children’s strengths and difficulties in child psychiatry.23,24 It consists of 25 items, 14 describe perceived difficulties, 10 perceived strengths and one is neutral (‘gets on better with adults than with other children’). Each perceived difficulties item is scored on a 0-2 scale (not true, somewhat true, certainly true). Each perceived strengths item is scored in the reverse manner, i.e., 2: Not true, 1: Somewhat true, 0: Certainly true. There are three versions of this questionnaire, one for parents, teachers, and one for children above 11 years. The 25 SDQ items are divided into scales of hyperactivity, emotional problems, conduct problems, peer problems and prosocial scale (five items per scale). A score is calculated for each scale (range 0-10) and a total difficulties score for the four scales (excluding prosocial behaviour, which was considered different from psychological difficulties), i.e., a range of 0-40. The SDQ has been previously used in the Palestinian culture.22,25

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale26

This measure consists of 44 items; of which 38 reflect specific symptoms of anxiety and 6 relate to positive, filler items to reduce negative response bias. Of the 38 anxiety items, independent judges considered 6 to reflect obsessive-compulsive problems, 6 separation anxiety, 6 social phobia, 6 panic/3 agoraphobia, 6 generalized anxiety/overanxious symptoms and 5 items concerning fears of physical injury. Items are randomly allocated within the questionnaire. Children are asked to rate on a 4 point scale involving never (0), sometimes (1), often (2) and always (3), the frequency with which they experience each symptom. The instructions state “Please put a circle around the word that shows how often each of these things happens to you. There are no right and wrong answers”. Given that the scale examines the occurrence of objective, clinical symptoms, it was considered appropriate to apply a frequency scale, rather than an intensity scale. The 0-3 ratings on the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) are summed up for the 38 anxiety items to provide a total score (maximum=114), with high scores reflecting greater anxiety symptoms. Scores may also be produced for the anxiety subscales using items as outlined in Table 1. There are six, positively worded filler items. These include item 11 (I am popular among other kids of my own age), item 17 (I am good at sports), item 26 (I am a good person), item 31 (I feel happy), item 38 (I like myself) and item 43 (I am proud of my school work). Responses to each of the positively-worded filler items are ignored in the scoring process. It was validated in Palestinian society before and showed high reliability.27

| Table 1: Prevalence of General Mental Health Problems using SDQ by Self, Teachers, and Parents. |

| Abnormal |

Teachers |

Parents |

Self-reported |

| SDQ caseness |

28.4 |

24.3 |

19.4 |

| Hyperactivity |

3.8 |

6.3 |

4.7 |

| Emotional problems |

7.8 |

19.8 |

9.9 |

| Conduct problems |

47.0 |

53.3 |

40.3 |

| Peer problems |

21.2 |

27.8 |

18.5 |

The Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problems Experiences28

The Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences (A-COPE) is a self-report instrument that describes and measures coping strategies during adolescence. This is based on the theoretical framework of coping being viewed as one of the four components that interact and influence adolescent development and adaptation (the remaining three being demands, resources and definitions/meaning). This model was based on the integration of individual coping theory and family stress theory. The instrument consists of 54 items measuring specific coping behaviours that adolescents may use to manage and adapt to stressful situations. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1=never; to 5=most of the time) to indicate how often they use each coping strategy when feeling tense or facing a problem. The following 12 sub-scales (each consisting of between 2 and 8 items) were identified by principal-component analysis.29

Engaging in demanding activity (posing challenges to excel at something or achieve a goal through physical activity, schoolwork or improving oneself); developing self-reliance and optimism (direct efforts to be more organized and in charge of the situation, as well as to think positively); developing social support (helping others solve problems, talking to friends, apologizing); seeking diversions (efforts to keep busy and engage in relatively sedate activities such as sleeping, watching TV or reading); solving family problems (working out difficult issues with family members and having joint activities with the family); seeking spiritual support (focused on religious behaviours such as praying, going to church or talking to clergy); investing in close friendships (seeking closeness and understanding from a peer); use of humour (not taking the situation too seriously by joking or making ‘light’ of it); seeking professional support (getting help and advice from a professional such as a counsellor or teacher about problems); relaxing (ways to reduce tension such as daydreaming, listening to music or cycling); ventilating feelings (expression of frustration and tension through yelling, blaming others, making mean comments, and complaining to friends or family); and avoiding problems (use of substances as a way to escape, or avoiding persons or issues that cause problems). The instrument was translated to Arabic language and was previously used in Gaza Strip.30

Study Procedure

Data was collected by 4 trained social workers and community mental health workers with previous experiences in data collection in similar projects (2 males and two females). They were trained by the consultant and project assistant on questionnaires of the study. Data collectors were provided with a prepared list of 10 schools names (6 from governmental sector and 4 from UNRWA) with number of children according to age and sex. They were permitted to enter the schools after getting permission from UNRWA and Ministry of Education (MoE) in Gaza and then they met the Rafah directors to give permission to the school head teachers to enter the schools. Children were randomly selected by choosing one class according to age from the registration book of the class. We obtained by a written agreement from the Ministry of Education and UNRWA education department to do the work in schools. A covering for each child was send to parents explaining the aim of the study and about their right not to participate with their children in study and ask them to sign the letter and send it back to school with children if they agree to participate with their children in the study.

Statistical Analysis

After the collected data was entered into the system using SPSS (SPSS win, Ver 20) for data entry and analysis and the validity and reliability of the instruments using split half method and Cronbach’s alpha equation. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to present the data patterns for the whole sample. Gender subgroups were compared on questionnaire continuous scores by two-tailed t-test. The association between exposure to trauma and violence and faction war and PTSD symptoms (CPTSD-RI), SDQ parents, teachers, and self, anxiety, coping strategy was investigated by a series of vicariate regression analysis. Finally, the interaction between exposure to trauma and each coping strategy was also included.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Data

From a total of 317 children, parents and teachers responded to our study. The sample consisted of 161 boys which represented 50.8% and 156 girls which represented 49.2% of the student population. The children aged between 9-16 years recorded a mean age 12.51 (SD=2.2).

The boys’ mean age was 12.66 years (SD=2.1), and the girls’ mean age was 12.38 (SD=2.28). Palestinian families consisted of large number of children, as 99 (31.2%) had 4 or less children, 129 families (40.7%) had 5-7 children, and 89 families (28.1%) had 8 or more children. Two hundreds and four children (64.4%) lived in the city, 80 (25.2%) lived in refugee camps, and 33 children (10.4%) lived in villages.

The majority of families (188, or 59.3%) had a very low monthly income of less than $289, 67 families (21.1%) had an income of $ 290-481, 38 families (12%) had a monthly income of more than $ 482-722, and 24 families (7.6%) had a monthly income of more than $ 723 (Table 2).

| Table 2: Sociodemographic Characteristic of the Study Sample (N=317). |

|

No |

% |

| Sex |

| Male |

161 |

50.8 |

| Female |

156 |

49.2 |

| Age aged from 9-16 years with mean age 12.51 (SD=2.2) |

| Place of residence |

|

|

| City |

204 |

64.4 |

| Camp |

80 |

25.2 |

| Village |

33 |

10.4 |

| No of siblings |

| 4 and less |

99 |

31.2 |

| 5-7 siblings |

129 |

40.7 |

| 8 and more siblings |

89 |

28.1 |

| Family monthly income |

| Less than$ 289 |

188 |

59.3 |

| $ 290-481 |

67 |

21.1 |

| $ 482-722 |

38 |

12.0 |

| More than $ 723 |

24 |

7.6 |

Types and Severity of Traumatic Events

As shown in Table 3, Palestinian children were exposed to a variety of traumatic events ranging from 0-28 traumatic events, each child reported experiences of 9.34 traumatic events (SD=4.88). The most common traumatic experiences were hearing shelling of the area by artillery (89.9%), watching mutilated bodies in TV (89.9%), Hearing the sonic sounds of the jet fighters (84.9%), and witnessing the signs of shelling on the ground (71.6%). While the least common traumatic events were threatening family members of being killed (8.2%), and threatened of being killed (7.9%).

| Table 3: Types of Traumatic Events. |

| Trauma |

No |

% |

| Hearing shelling of the area by artillery |

285 |

89.9 |

| Watching mutilated bodies in TV |

285 |

89.9 |

| Hearing the sonic sounds of the jetfighters |

269 |

84.9 |

| Witnessing the signs of shelling on the ground |

227 |

71.6 |

| Witnessing assassination of people by rockets |

164 |

51.7 |

| Hearing killing of a close relative |

152 |

47.9 |

| Deprivation from water or electricity during detention at home |

150 |

47.3 |

| Witnessing of a friend home demolition |

121 |

38.2 |

| Hearing killing of a friend |

116 |

36.6 |

| Witnessing firing by tanks and heavy artillery at neighbours homes |

112 |

35.3 |

| Being detained at home during incursions |

98 |

30.9 |

| Witnessing of own home demolition |

79 |

24.9 |

| Threaten by shooting |

76 |

24.0 |

| Threaten by telephoned to evacuate your home before bombardment |

71 |

22.4 |

| Witnessing firing by tanks and heavy artillery at own home |

65 |

20.5 |

| Witnessing arrest or kidnapping of someone or a friend |

64 |

20.2 |

| Witnessing shooting of a friend |

61 |

19.2 |

| Deprivation from going to toilet and leave the room at home where you was detained |

54 |

17.0 |

| Witnessing killing of a friend |

53 |

16.7 |

| Witnessing shooting of a close relative |

51 |

16.1 |

| Destroying of your personal belongings during incursion |

47 |

14.8 |

| Witnessing killing of a close relative |

45 |

14.2 |

| Shooting by bullets, rocket, or bombs |

44 |

13.9 |

| Beating and humiliation by the army |

43 |

13.6 |

| Threatened to death by being used as human shield to arrest your neighbours by the army |

34 |

10.7 |

| Physical injury due to bombardment of your home |

32 |

10.1 |

| Threaten of family member of being killed |

26 |

8.2 |

| Threaten of being killed |

25 |

7.9 |

Sociodemographic Differences and Exposure to Traumatic Events

In order to investigate the sex differences between boys and girls in reporting traumatic experiences, independent t-test was performed. The results showed that boys were exposed to more traumatic events than girls (mean=9.9 vs. mean=8.76). This was statistically significant (p=0.03). The results showed that older age group children (13-16 years) were exposed to more traumatic events than the younger age group. This was statistically significant (p=0.001).

Type of Post-Traumatic Stress Reactions

Among Palestinian children, the most commonly reported post traumatic stress reactions were loss of interest in significant activities (64.7%), sleep disturbance (51.7%), avoidance of reminders (47.6%), intrusive images and sounds (43.3%), and difficulty in concentrating (43.2%).

Severity of Post Traumatic Stress Reactions

Children’s post-traumatic stress reactions scores ranged between 5 and 59. Mean CPTSD-RI was 31.15 (SD=11.66). Intrusion subscale mean was 11.19 (SD=5.4), avoidance subscale mean was 7.21 (SD=3.73), and hyperarousal subscale mean was 7.68 (SD=3.46). Twenty one (6.6%) children reported no post-traumatic stress reactions, 69 (21.8%) reported mild post-traumatic stress reactions, 147 (46.4%) reported moderate post-traumatic stress reactions, and 80 (25.2%) reported severe to very severe post-traumatic stress reactions. Using cut-off point of 40 and more as PTSD, 25.2% of children met the diagnosis of PTSD and 74% had no PTSD.

Sociodemographic Differences on Severity of Post-Traumatic Stress Reactions

There were statically significant sex differences in developing post-traumatic stress reactions in which girls developed more PTSD than boys (χ2=14.19, d.f.=3, p<.003). The results showed than girls significantly developed more PTSD than boys (Mean=33.58 vs. 28.79), also more girls developed intrusion symptoms than boys (mean=12.10 vs. 10.31), avoidance symptoms (mean=8.21 vs. 6.3), and also hyperarousal was more in girls (mean=8.05 vs. 7.32). The results showed that older age group children (13-16) developed PTSD more than the younger age group. This was statistically significant (t=-2.20, p=0.01). Also, the older group developed intrusion symptoms more than the younger age group (t=-2.49, p=0.01) and hyperarousal symptoms (t=-2.18, p=0.03). However, no age differences was observed for avoidance symptoms.

Anxiety Symptoms

Addressing the anxiety symptoms reported by children, 59.6% said that they are worried that something awful will happen to someone in their families, (56.2%) have to think of special thoughts to stop bad things from happening (like numbers or words), and they are proud of their school work (51.4%).

Means and Standard Deviations of Anxiety Disorders in

Children

Children recorded from 0-114 symptoms of anxiety, total score of anxiety was 41.15 (SD=20.02), obsessive compulsive disorder mean was 8.4 (SD=3.4), social phobia 7.3 (SD= 4.1), generalized anxiety mean was 6.7 (SD=4), separation anxiety mean was 6.5 (SD=4.2), physical injury fears was 5.3 (SD=4.2), panic/agoraphobia was 7 (SD=5.4).

Sociodemographic Differences in Anxiety of Children

The results showed that girls showed more total anxiety score (t=-7.74, p=0.001), girls also experienced more panic/agoraphobia (t=-5.32, p=0.001), and more separation anxiety (t=-7.92, p=0.001), than boys, however no differences were observed for obsessive compulsive disorder (t=0.38, p=ns). The results showed that children aged between 9-12 years showed more panic/agoraphobia than children aged between 13-16 years (t=2.5, p=0.01), physical injury fears were more in children aged between 9-12 years relative to other age groups (t=2.52, p=0.01), social phobia were also more in children aged between 9-12 years than the older age group (t=3.07, p=0.002), obsessive compulsive disorder was more in children aged between 13-16 years relative to the younger age group (t=2.88, p=0.004), however no differences were observed in anxiety, separation anxiety, or generalized anxiety.

Prevalence of General Mental Health Problems Using SDQ

Using SDQ for self, 19.4% of the children rated themselves as having caseness (were considered as having a problem), 4.7% of them were hyperactive, 9.9% had emotional problems, 40.3% had conduct problems, and 18.5% had peer problems.

Using SDQ for parents, 24.3% of the children were rated as having caseness (were considered as having a problem), 6.3% of them were hyperactive, 19.9% had emotional problems, 53.3% had conduct problems, and 27.8% had peer problems. Using SDQ for teachers, 28.4% of the children were rated as having caseness (were considered as having a problem), 3.8% of them were hyperactive, 7.8% had emotional problems, 47% had conduct problems, and 21.2% had peer problems.

Sociodemographic Differences in SDQ Scores

The results showed that girls showed more mental health problems than boy according to their teachers (mean=13.9 vs. mean=11.9) (t=-3.2, p=0.01). There were no sex differences in rating mental health problems by themselves and their parents.

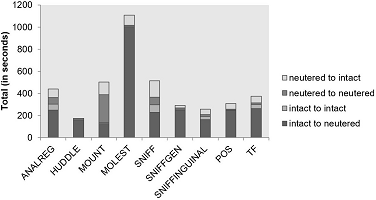

Types of Coping Strategies

Children used a variety of coping strategies. The most common coping strategies used by children were: 71.6% of children said they go along with their parents and rules, 64.1% try to improve themselves (get body in shape, get better grades, etc.), 64.1% of them pray, 59.9% work hard on schoolwork or other school projects, 52.8% do things with their family. While the least common coping strategies used were: drinking beer, using sedatives (4.6%) and smoking (3.1%).

Means and Standard Deviation of Coping Strategies

Children used a group of coping strategies to overcome trauma and stress, mean total ACOPE was recorded as 187.5 (SD=21.3), while the highest subscale of coping was for seeking professional support (mean=36.6, SD=1.4), seeking diversion (mean=22.7, SD=5.4), solving family problems (mean=20.9, SD=4.9), developing social support (mean=19.2, SD=4.2), developing self-reliance (mean=18.4, SD=4.7), ventilating feelings (mean=15.7, SD=3.8), engaging in demanding activities (mean=14.3, SD=3.1), relaxing (mean=10.3, SD=3.3), seeking spiritual support (mean=10.1, SD=3.0), avoiding problems (mean=8.1, SD=3.3), being humorous (mean=5.9, SD=1.8), and investing in a close friend (mean=5.8, SD=2.3) (Table 4).

| Table 4: Means and Standard Deviation of Coping Strategies. |

| Coping |

Mean |

SD |

| Total ACOPE |

187.5 |

21.4 |

| Seeking professionals support |

36.6 |

1.4 |

| Seeking diversion |

22.7 |

5.4 |

| Solving family problems |

20.9 |

4.9 |

| Developing social support |

19.2 |

4.2 |

| Developing self-reliance |

18.4 |

4.7 |

| Ventilating feelings |

15.7 |

3.8 |

| Engaging in demanding activities |

14.3 |

3.1 |

| Relaxing |

10.3 |

3.3 |

| Seeking spiritual support |

10.1 |

3.0 |

| Avoiding problems |

8.1 |

3.3 |

| Being humorous |

5.9 |

1.8 |

| Investing in close friend |

5.8 |

2.3 |

Sociodemographic Differences in Coping Strategies

The results showed that boys generally cope better than girls (t=2.12, p=0.04), Boys also seek diversion more than girls (t=3.84, p=0.001), and seek spiritual support (t=6.98, p=0.001).

Relationship between Traumatic Events and Child Mental Health Problems

To test the hypothesis underlying the relationship between violence (traumatic events) and mental health in children, correlation coefficient test was performed using the Pearson correlation. The results showed that there was a strong association between trauma and total scoring of mental health problems by teachers (r=.13, p=0.04). There was an association between trauma and mental health problems rated by the children themselves (r=0.15, p=0.03) (Table 5).

| Table 5: Pearson Correlation Coefficient test between Trauma and SDQ. |

|

Trauma |

| Variables |

R |

| SDQ total -teachers |

0.13* |

| SDQ total-parents |

0.09 |

| SDQ total-self |

0.15* |

| *p<0.05,** p<0.01,** p<0.001, p>0.05 |

Relationship between Trauma, Anxiety, General Mental Health, PTSD, and Coping Strategies

To test the hypothesis underlying the relationship between PTSD and coping strategies used by children to overcome violence and related consequences, correlation coefficient test was performed using Pearson correlation. The result showed that there was a strong association between total traumatic events and PTSD (r=0.14, p=0.01) (Table 6).

| Table 6: Correlation Coefficients between Coping Strategies and Trauma, PTSD, and Anxiety. |

|

Total trauma |

Total CPTSRI |

Total anxiety |

| Total trauma |

1.00 |

0.14** |

0.11 |

| Total CPTSRI |

0.14** |

1.00 |

0.40** |

| Total anxiety |

0.11 |

0.40** |

1.00 |

| Total ACOPE |

-0.02- |

0.14 |

0.15** |

| Ventilating feelings |

-0.04- |

0.27** |

0.27** |

| Seeking diversion |

-0.05- |

-0.05- |

-0.08- |

| Developing self-reliance |

0.12 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

| Developing social support |

0.01 |

0.14** |

0.27** |

| Solving family problems |

-0.04- |

-0.05- |

0.00 |

| Avoiding problems |

0.04 |

0.21** |

0.12 |

| Seek spiritual support |

0.04 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

| Investing in close friends |

0.04 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

| seeking professional support |

0.05 |

0.09 |

0.05 |

| Seeking engaging in demanding activity |

-0.10- |

0.06 |

0.01 |

| Being humorous |

0.04 |

0.12** |

0.08 |

| Relaxing |

-0.13- |

-0.05- |

0.17** |

| *p<0.05,** p<0.01,** p<0.001, p>0.05 |

Total PTSD was correlated with total anxiety (r=0.40, p=0.001), ventilating feelings (r=0.27, p=0.01), developing social support (r=0.14, p=0.01), avoiding problems (r= 0.21, p=0.01), and being humorous (r=0.12, p=0.01).

Total anxiety was correlated with total coping (r=0.15, p=0.001), total PTSD (r=0.40, p=0.01), ventilating feelings (r=0.27, p=0.01), developing social support (r=0.27, p=0.01), and relaxing (r=0.17, p= 0.01).

Prediction of PTSD by Traumatic Events by Political Violence

In order to test the predictive value of specific traumatic events on PTSD symptoms, total CPTSD-RI was entered as the dependent variable in logistic regressions, with 28 types of traumatic events as the covariates. The event that was significantly associated with PTSD was beating and humiliation by the army (β=0.16 p=0.01), witnessing arrest of someone or a friend (β=0.14, p=0.01) (F=7.12, p=0.001) (Table 7).

| Table 7: Logistic Regression Analysis of PTSD and Types of Traumatic Events. |

| |

Unstandardized

Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

p |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B |

| |

B |

Std. Error |

β |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| (Constant) |

30.54 |

0.87 |

|

35.30 |

0.01 |

28.84 |

32.24 |

| Beating and humiliation by the army |

6.25 |

2.27 |

0.16 |

2.76 |

0.01 |

1.79 |

10.71 |

| Witnessing arrest or kidnapping of someone or a friend |

2.30 |

0.93 |

0.14 |

2.49 |

0.01 |

0.48 |

4.12 |

Prediction of Mental Health Problems Due to Political Violence

In order to investigate the relative predictive value of trauma on the development of different mental health problems, a series of linear regression analyses were performed. Total traumatic events were entered as the dependent variable, and mental health problems, PTSD, and anxiety, as independent variables.

The results showed that traumatic events were predictive of mental health problems, number of traumatic events and hyperactivity by teachers (β=0.19, t=3.4, p<0.01). General mental health problems rated by teachers (β=0.14, t=2.5, p<0.01), general mental health problems rated by children (β=0.14, t=2.1, p<0.05), PTSD also was predicted by traumatic events (β=0.39, t=7.5, p<0.01). However, traumatic events were negatively predictive of social problems rated by children themselves (β=-0.14, t=-2.0, p<0.05) (Table 8).

| Table 8: Linear Regression Analysis between Total Trauma and Children Mental Health Problems. |

| Independent variables |

β |

R2 |

t |

F |

| Hyperactivity-teachers |

0.19 |

0.03 |

3.4** |

11.7** |

| SDQ total -teachers |

0.14 |

0.02 |

2.5** |

6.5** |

| Social problems-self |

0.14- |

0.02 |

-2.0* |

*4.2* |

| SDQ total-self |

0.14 |

0.02 |

2.1* |

*4.5 |

| PTSD |

0.39 |

0.15 |

7.5** |

**57.5 |

| *p<0.05, ** p<0.01, ** p<0.001, p>0.05 |

DISCUSSION

In our study each Palestinian child was exposed to 9.34 traumatic events due to political violence and the most common traumatic experiences were hearing shelling of the area by artillery, watching mutilated bodies in TV (89.9%), hearing the sonic sounds of jet fighters, and witnessing the signs of shelling on the ground. This is similar to our study of children in North Gaza and Middle area after incursion.20,31,32,33,34,35,36

Bosnian children reported other types of traumatic events such as separation from parents, death of parents or siblings, and extreme poverty or deprivation.8 From the above mentioned studies, we can conclude that each culture and area may need a certain measure of exposure to trauma in order to adapt to the type of conflict and the involvement of children and their families. Our study showed that boys were exposed to more traumatic events than girls due to political violence. This finding concerning the risks of trauma in boys was consistent with the previous studies in the Gaza Strip.31,32,35,36,37 This high exposure was attributed to cultural factors in which boys moved aside during incursions and bombardment and witnessed the remnant of the martyrs in the streets. While Palestinian girls are protected and kept at home and not allowed going outside the home. Our results showed that older age group children (13-16 y) were exposed to more traumatic events than the younger age group. This due to the fact that the young children are kept at home with their parents and the older children are more active outside their homes. The strong association established between traumatic events and severity of PTSD reactions support the linear relationship between trauma and PTSD in children. Our findings were congruent with those of the previous studies.35,36,37 Our study showed that the rate of PTSD was 25.2%. This rate was less than the studies done in the north and the middle area of the Gaza Strip in which 71% of the children were considered to be suffering from PTSD.31 Our results were consistent with the results of the study on of children and adolescents aged between 8-16 years in Gaza and the West Bank. The frequency of PTSD scores above the established cut-off score (likely PTSD) was 21.2%. There was significant association between exposure to traumatic events and PTSD symptoms.32

This study showed that girls developed more PTSD than boys. This is consistent with the results from similar studies in other parts of the world.8,21,38,39 However, the results showed that older age group children (13-16 y) developed more PTSD than the younger age group thus, more intrusion, and hyperarousal symptoms. These findings have been replicated in other cultural groups.40 This was inconsistent with the results our previous study on the effect of shelling in children.31,35,36

According to this study, the prevalence of mental health problems rated by teachers and parents were less than previously recorded rates in the study in of the children (38.5%) from Gaza were rated as having caseness by teachers and (36.9%) by parents.20

Girls reported more mental health problems by themselves than boys. Children aged between 13-16 years reported more mental health problems by themselves than the younger age group.

Anxiety disorders represent one of the most common forms of child psychopathology. The children’s total score of anxiety was 41.15, obsessive compulsive disorder mean was 8.4, social phobia 7.3, generalized anxiety mean was 6.7, separation anxiety mean was 6.5, physical injury fears was 5.3 and panic/agoraphobia was 7. The present study was consistent with the study of labor children in the Gaza Strip in which the mean total anxiety score was recorded as 48.15.27 Our results were inconsistent with study of a community sample of 2,052 children between 8-12 years of age. Lower scores of total anxiety and other were reported.21 Our results were consistent with the study on the effect of home demolition of Palestinian anxiety; they found that children whose homes were demolished showed significantly more psychological symptoms than the children in witness control groups. The age of children was not significantly related to psychological symptoms.41 Our results showed that total anxiety scores, generalized anxiety, social phobia, panic/agoraphobia, social phobia, and physical injury fears were statistically significant in children of the younger age. The results showed that girls reported a higher total anxiety score more panic/agoraphobia and more separation anxiety than boys. The results showed that children aged between 9-12 years showed more panic/agoraphobia than children aged between 13-16 years, physical injury fears were more in children aged between 9-12 years than other age group, social phobia was also more in children aged between 9-12 years than the older age group, obsessive compulsive disorder was more in children age between 13-16 years compared to the younger age group. Our study is inconsistent with the study of a community sample of 2,052 children, between 8-12 years of age. Lower scores of total anxiety and other subscales were recorded.42 Our results consisted with study of sample consisted of 358 adolescents which showed the mean total anxiety was 41.18.33

The children mean total coping strategies was 187.5 for children, while the highest subscale of coping was towards seeking professional support, seeking diversion, solving family problems, developing social support. The results showed that boys generally cope better than girls, boys also seek diversion more than girls, and seek spiritual support. The results showed that there was a strong association between PTSD and total coping strategies, ventilating feelings and PTSD, social support and PTSD, avoiding problems and PTSD. Our results were consistent with the previous studies in the Gaza Strip.30,32-34,43 Our results were inconsistent with the results that found children used instrumental social support (81.2%), instrumental emotional support (75.9%), religious coping (59.8%), and humor (50.8%).44 Also, others found that a majority of the children’s coping responses in the study of stressors and coping behaviors of school-aged homeless children staying in shelters were in the social support (86%), cognitive avoidance (38%), and behavioral distraction categories (31%). While 17% were in the cognitive restructuring category, 14% in information seeking category, 10% in isolating activities and 3% in seeking spiritual support.45 Also, the results of the study on adolescents who reported coping strategies among two groups were exposed to different stressors; the groups of different stressful situations have indicate 55% active coping, 19.29% distraction, 27.11% avoidance, 17.97% support-seeking, and social support 18.64%.46 The study showed that adolescents who experienced traumatic experiences developed less social support and positively asked for more professional support as coping strategies. Adolescents with PTSD had showed coping by ventilating feelings, developing social support, avoiding problems, and adolescents with less PTSD were more focussed towards solving their family problems. Adolescents with anxiety were associated with ventilating feelings, developing social support, and engaging in demanding activities. Adolescents with less anxiety were seeking more spiritual support. Such findings were consistent with the previous studies in the area.32,33,34

CONCLUSION

The study showed that Palestinian children were exposed to 9.34 traumatic events due to political violence. Boys and older age children were more traumatized. There was a strong association between traumatic events and the severity of PTSD reactions. Girls showed more PTSD than boys and older age group children developed more PTSD than the younger age group. Our study showed that prevalence of general mental health problems using SDQ by children aged 11 years and more using SDQ for self, parents and teachers (19.4%, 24.3%, and 28.4% of children respectively were rated as having caseness). Anxiety disorders represent one of the most common forms of child psychopathology. The results showed that girls showed more total anxiety. Palestinian children used a group of coping strategies to overcome trauma and stress, the highest subscale of coping was seeking professional support, seeking diversion, solving family problems, developing social support, developing self-reliance, ventilating feelings, engaging in demanding activities, relaxing, seeking spiritual support, avoiding problems, being humorous, and investing in close friend. The result showed that there was strong association between PTSD and total coping strategies, ventilating feelings and PTSD, social support and PTSD, avoiding problems and PTSD.

Clinical Implications

The finding of this study highlighted the need to establish outreach child mental health clinics with multidisciplinary staff at primary health centers to assess and treat children referred from community agencies and schools after exposure to traumatic events. Also, continuous training programmes conducted by child mental health professionals for primary health physicians and nurses, in order to enable those professionals to diagnose detect children with PTSD and other psychiatric disorders, and to manage less complex cases at the primary care level. School-based prevention and treatment programmes need to be developed and supported, as schools provide access to a developmentally appropriate environment that encourages normality and minimizes stigma. School is also a setting in which PTSD and associated symptoms are likely to emerge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We appreciate the support given by World Vision Australia to conduct this study, to children, families, and teachers participating in this study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There were no conflicts of interest in conducting this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Authors AMT designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author SST preformed the data collection, statistical analysis and managed the literature search. Author AMT wrote the first draft of the manuscript with the author’s assistance. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.