CASE REPORT

A 35 year-old man presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic abdominal pain, Nausea and Vomiting (N&V). The pain was severe, unrelenting and affected the entire abdomen with an epicenter in the Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ). He also experienced vomiting every 15-20 minutes. After several episodes of emesis, he had noticed sharp and then continuing pain in the center of the chest.

He had a long history of sudden episodes of abdominal pain, starting at the age of twenty. Initially, he had suffered from a sudden onset of pain associated with nausea and vomiting with a frequency of more than 20 times per day. Typically, such episodes woke him up in the early morning hours, persisted for several hours and eventually led to dehydration, requiring emergency room visits and even repeated hospitalizations. He could often alleviate milder symptoms by taking hot showers or baths. Emetic episodes lasted for up to one week and were followed by prolonged asymptomatic periods. However, his symptoms gradually progressed. Eventually, he received chronic opioid therapy for the recurrent pain, which was associated with an even more significant rise in the frequency of exacerbations. He had previously been diagnosed as suffering from irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety and depression. During the 6 years prior to his current presentation, he had undergone more than 20 abdominal computerized tomographies and ten upper endoscopies, which had all shown varying degrees of esophagitis or occasional Mallory Weiss tears. Additional diagnostic studies had excluded pancreatic disease, hereditary angioedema, porphyria, gastroparesis, and small bowel or colonic disease.

His outpatient medications included buprenorphine and naloxone, hydromorphone as needed, dicyclomine, gabapentin and citalopram. He regularly smoked marijuana since his teenage years. His family history was negative for migraines or CVS.

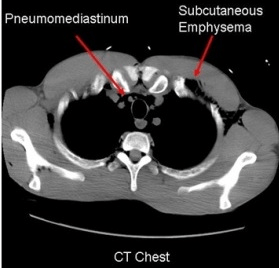

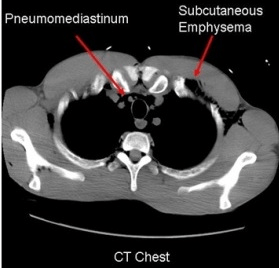

On admission, he complained about severe pain, was normotensive, but tachycardic. The key physical examination findings were a dry oral mucosa, subcutaneous crepitus in neck and anterior chest and diffuse abdominal tenderness without guarding or rebound. He had evidence of dehydration with hemoglobin of 18 g/dl, hematocrit 54.1%, and a creatinine of 4.2 mg/dl with associated anion ion gap acidosis. Imaging studies demonstrated a pneumomediastinum (Figure 1) with subcutaneous emphysema. As an esophagram did not show a contrast leak, he was treated conservatively with intravenous fluids, antiemetics, analgesic agents, acid suppression and antibiotics. He recovered and was discharged with the diagnosis of coalescent CVS, complicated by an esophageal microperforation. His treatment goal was to taper and then completely discontinue opioids and to stop cannabinoid use. To blunt the expected autonomic response associated with withdrawal, he received clonidine and was switched from citalopram to a Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA).

Figure 1: Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema

DISCUSSION

This case highlights several key points that are important for patients and physicians who deal with CVS, an unexplained disorder first described in children but now increasingly recognized in adults. The patient’s esophageal perforation was a secondary complication of repetitive vomiting, which more commonly causes esophagitis or gastrointestinal bleeding due to Mallory Weiss tears. Even though the apparent microperforation of the esophagus is an extreme example, it still emphasizes the need to identify an underlying disorder rather than focusing exclusively on the important consequences of repetitive vomiting. While only seen in a subset of patients, the case also illustrates the fact that CVS can undergo a phenotypic switch from its classic, dichotomous patterns of emetic and asymptomatic phases to eventual coalescence of increasingly frequent attacks with chronic nausea and pain complicated by typical exacerbations.1,2 Only a detailed history revealed that the patient clearly met diagnostic criteria for CVS (Table 1) at the onset of his illness. The progression of his illness was associated with the introduction of chronic opioid use to control symptoms, a change that has been linked the development of refractory disease.3

| Table 1: Criteria for CVS in adults and children. |

|

Adults – Rome III

Criteria11

|

Children – *NASPGHAN

Guidelines12

|

| Must include all of the following:

1. Stereotypical episodes of vomiting with

a) Acute onset

b) Duration <1 week

2. Three or more discrete episodes in the prior year.

3. Asymptomatic intervals between emetic phases.

Supportive criterion: Personal or family history of migraine headaches. |

1. At least 5 attack in any interval, or a minimum of 3 attacks during a 6 month period.

2. Episodic attacks of intense nausea and vomiting lasting 1 h-10 days and occurring at least 1 week apart.

3. Stereotypical pattern and symptoms in the individual patient.

4. Vomiting during attacks occurs at least 4 times/hour

5. Asymptomatic intervals between emetic phases.

Absence of other specific causes. |

| *NASPGHAN: North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition |

Diagnosing CVS remains a challenge, and many patients undergo repeated and typically negative diagnostic evaluations, or even surgical treatments, before the diagnosis is entertained. Tests do not only constitute a financial burden, but also come with a risk, for example due to cumulative radiation exposure with radiographic testing or the risk of repeated endoscopic evaluations. The patient’s history also supports the need to recognize the strong association of cannabinoid use with the development of CVS, as cannabis use has been found to contribute to the development of CVS in about 50% of the patients.4,5,6,7

Acutely, the patient improved with symptom-driven management strategy that largely relied on intravenous analgesics, antiemetics and fluids.8 However, long-term treatment of CVS with preventative strategies is essential to reduce the number of attacks. After recognizing the disease, physicians need to identify potential triggers, such as opioid and cannabinoid use, both of which contributed in the case described. With the emergence of dependence, discontinuation of opioids or cannabinoids will trigger withdrawal symptoms that mirror emetic episodes of CVS. Thus, a slower taper may be required to prevent withdrawal in these individuals. In addition, clonidine and TCAs should be considered to blunt to autonomic response associated with withdrawal.9 TCAs remain the treatment of choice as preventative therapy for patients with CVS.2 Should TCAs fail or be contraindicated, coenzyme Q10 or anticonvulsive drugs may be acceptable alternatives.10,11,12 Seen in a broader context, our observation suggests that coalescing CVS is a foregut manifestation of the narcotic bowel syndrome and will require a multidisciplinary approach to achieve long-term remission.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosure to make.

CONSENT

No consent is required to our article publication.