INTRODUCTION

Berries are rich in antioxidants such as vitamin C and phytophenols.1 Experiments have shown that phytophenols may possess antioxidant, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory,2,3 antibacterial and antiviral activities.4 Phytophenols can counteract upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) by the destruction of microbes, and preventing their adhesion to mucous membranes.5 Furthermore, phytophenols may be beneficial for health by promoting the innate immunity.6 Moreover, vegetarians have lowered incidence of inflammatory processes.7

URTI-risk is highest during cold seasons8 and especially during winter months. The URTI-risk also increases when peoples are gathering or interact with each other.9 This occurs when new conscripts start their military service. Moreover, exhaustive exercise may increase the URTI-risk, and during open window phase of weaker resistance, viruses and bacteria may be more infective, thus increasing infection risk.10 Thus, the physical demands of the military service may increase URTI-risk. Among Finnish conscripts URTI is most important reason for service reliefs and hospital visits during military service.11

Our earlier infection frequency crossover study among small group of young cross-country skiers showed that phytophenol rich berry-vegetable nectar had a health promoting potential: total URTI-days diminished during intervention as compared to control period.12 Previously we have also observed that quercetin content of samples correlated strongly with the inhibition of the bacterial cultures while using agar diffusion assay.

We hypothesized that phytophenols may help to decrease morbidity and/or alleviate the symptoms in a large number of peoples during URTI epidemics. There are no corresponding studies where the uniform age group of participants in partly isolated society with similar physical training and with the similar menu ad libitum would be supplemented by berry-vegetable nectar to detect effects on need of health services during high URTI-risk period. Thus, we aim to clarify if the consequences of epidemical URTI-morbidity could be affected by supplementing the nutrition of conscripts by phytophenol rich berry-vegetable nectar.

METHODS

Subjects and controls were conscripts who started their military service at the beginning of January two weeks before intervention started. Garrison of Vekaranjärvi (Tuohikotti, Finland) includes 15 separate companies, in which conscripts do their military service. Companies are military groups and each company has their own military task such as “tank defense” or “military engineering”. Voluntary conscripts, who did their military service in a four of these 15 companies, represented intervention subjects (n=188) and conscripts who were not voluntary for berry-vegetable nectar supplementation in these same four companies served as company controls (n=359). Conscripts from other 11 military companies were called as other controls (n=1597). All conscripts were predominantly healthy men and approximately 18 to 21 years of old reflecting Finnish male population. In Finland, military service is mandatory for all predominantly healthy men and military service may be avoided only due to poor health or by performing alternative public service. Total drop-out during the intervention was 28% and at the end of the intervention number of intervention participants was 135. All of the intervention participants and controls lived in the similar military conditions within same garrison and had the similar menu ad libitum. The study plan was accepted by the Ethical Committee of the Kuopio University Hospital.

The intervention of 6.5 weeks was carried out during highest URTI-risk after conscripts start their military service in the beginning of January, 2001. The start time of intervention varied between companies less than one week, and the first week was running-in period. The intervention period was followed by post-intervention period of 2.5 weeks. Intervention subjects received three portions (100 ml) of berry-vegetable nectar (Lieksan Laatuherkut OY, Lieksa, Finland) (Table 1) per day: one at the breakfast, one at the lunch and one before going to sleep.

Table 1: Ingredients (A) of the berry-vegetable nectar and its contents of the energy, main vitamins (B) and flavonoids (C) (per 100 gram).

|

A)

|

Blackcurrant

|

27%

|

|

Strawberry

|

20%

|

|

Carrot

|

10%

|

|

Tomato

|

6%

|

|

Vegetable oil

|

–

|

|

Water

|

–

|

|

Sugar

|

–

|

|

Preservative E202

|

–

|

|

B)

|

Energy |

71.4 kcal

|

|

Protein

|

1 g

|

|

Carbohydrates

|

17 g

|

|

Fat

|

1 g

|

|

Vitamin C

|

30 mg

|

|

Vitamin E

|

3 mg

|

|

C)

|

Total flavonoids |

60 mg

|

|

Quercetin

|

1.4 mg

|

|

Myricetin

|

1.3 mg

|

|

Kaempferol

|

0.7 mg

|

|

Delphinidin

|

38.6 mg

|

|

Cyanin

|

14.7 mg

|

|

Pelargonidin

|

3.3 mg

|

Berry-vegetable nectar was manufactured without heating to preserve nutritional content, and berry-vegetable nectar was preserved within refrigerator temperatures (35.6 to 42.8 degrees of Fahrenheit) before eating. Participants got their berry-vegetable nectars by military personnel daily or required amount when subjects had camps or weekend frees.

When conscripts had health problems, they had opportunity to visit in the hospital clinic of the garrison. Depending on the severity of health problem, conscripts may be released from both indoor and outdoor military service or released only from in outdoor military service. Moreover, if health was poor enough, conscripts were hospitalized. Decisions of releases and hospitalizations were done by doctors, who were not aware of the study groups.

Afterwards, we got the number of company specific visits in hospital clinic and number of service relieves. In Finnish military forces URTI is most important reason for hospital visits and service reliefs during service.11 Moreover, highest URTI-risk was during study period.8 Unfortunately, detailed or individual diagnoses of the patients were not available, and hence we were unable to distinguish URTI from other causes. Moreover, the analyzed number of bed days in the hospital was defined by daily roll call data. Unfortunately, the data of roll calls in one of the intervention company was unavailable.

Statistical analyzes were done by comparing companies. Eleven of companies included other controls and four of companies included company controls and intervention subjects. The number of endpoint incidences such as the hospital visits, service relieves and bed days in the hospital in companies were scaled by the amount of conscripts. The number of endpoint incidences were calculated and reported week by week. The effect of intervention as compared with controls was explored by repeated measures analysis of variance. Moreover, differences between control and subjects were also detected by T-test. Correlations between endpoint incidences were computed by Pearson’s coefficients of correlation. Statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS software, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics

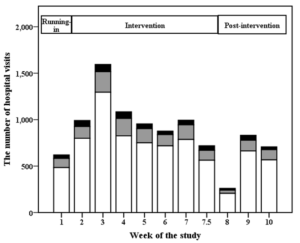

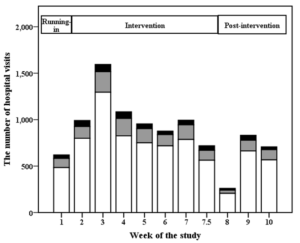

The total number of the hospital visits during study period has been presented in Figure 1. Moreover, table 2 presents the characteristics of endpoint incidences in control and intervention subject companies. The number of hospital visits week by week was associated with service reliefs from outdoor service (r 0.84; p<0.001) and with reliefs from all service (r 0.71; p><0.001). Furthermore, reliefs from outdoor service correlated with reliefs from all service (r 0.63; p><0.001). ><0.001) and with reliefs from all service (r 0.71; p< 0.001). Furthermore, reliefs from outdoor service correlated with reliefs from all service (r 0.63; p< 0.001)

Table 2: Weekly average and standard deviation values for the endpoint incidences during intervention and post-intervention. These values has been calculated between specific companies and scaled by number of conscripts.

| |

Intervention

|

Post-intervention

|

|

Releases from outdoor service

|

Releases from all service |

Days in the hospital |

Visits in hospital |

Releases from outdoor service |

Releases from all service |

Days in the hospital

|

|

Intervention subjects

|

Mean

|

1.08

|

1.67

|

0.43 |

0.46 |

0.81 |

0.56 |

0.22 |

0.65

|

|

SD

|

0.45

|

0.71

|

0.30 |

0.40 |

0.32 |

0.30 |

0.09 |

0.61

|

|

Company controls

|

Mean

|

1.55

|

2.07

|

0.54 |

1.08 |

0.81 |

0.52 |

0.16 |

0.43

|

|

SD

|

0.43

|

0.29

|

0.07 |

0.16 |

0.30 |

0.15 |

0.06 |

0.24

|

|

Other controls

|

Mean |

1.83

|

2.48

|

0.53 |

|

1.10 |

0.52 |

0.20

|

|

|

SD

|

0.33 |

0.60 |

0.12 |

|

0.36 |

0.18 |

0.11 |

|

Abbreviations: SD = Standard Deviation.

The number of companies: intervention companies (n=4, except for days in the hospital where n=3), company controls (n=4 except for days in the hospital where n=3), and other control companies (n=11). |

Figure 1: The total number of visits at the hospital during running-in, intervention and post-intervention periods represented week by week. Black color represents intervention subjects (n=188), and gray color refers company controls (n=359), and white color refers other controls (n=1597). Intervention ended between seventh and eight week and week number 7.5 refers three intervention days and week number 8 includes four post-intervention days.

The Number of Visits at the Hospital

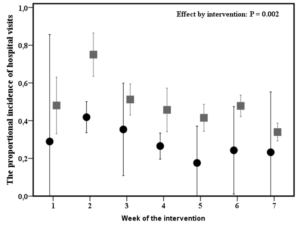

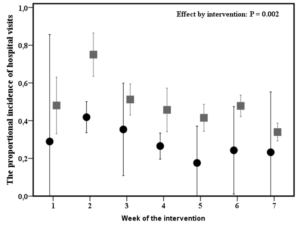

The intervention subjects visited less at the hospital clinic as compared to all controls during intervention according to repeated measures analysis of variance (p=0.002) (Figure 2). However, the difference in the total amount of visits during intervention as compared with company controls was not significant. During post-intervention period there were any differences between intervention subjects and control groups.

Figure 2: The average amount and 95% confidence interval of the visits at the hospital clinic in intervention (n=4, black circles) and in control (n=15, gray squares) companies week by week during the intervention. Effect by intervention has been analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance. Seventh week includes only three days

The Number of Reliefs from Outdoor Service

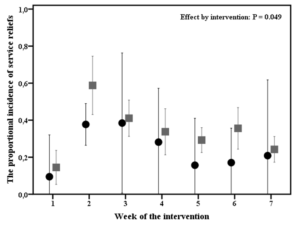

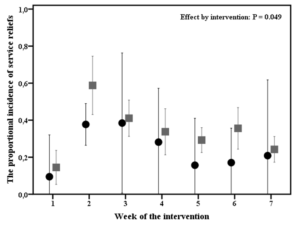

The intervention explained differences in the reliefs from outdoor service (p=0.049) (Figure 3) i.e. intervention subjects had the minor amount of releases from outdoor service as compared to all controls. The difference between the intervention subjects and company controls was not significant. Moreover, there were no differences during post-intervention period.

Figure 3: The average amount and 95% confidence interval of the reliefs from the outdoor service in intervention (n=4) and in control (n=11) companies week by week during the intervention. Group effect has been analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance. Seventh week includes only three days.

The Number of Reliefs from Outdoor and Indoor Service

The number of service reliefs from both in- and outdoor services was similar in intervention subjects to company controls, to other controls and to all controls during intervention and post-intervention.

The Number of Bed Days in the Hospital

Intervention did not effect on the amount of the bed days in the hospital during intervention (p≥0.067) when comparing intervention subjects and controls. Correspondingly, there were no significant differences during post-intervention period between intervention and control companies

DISCUSSION

Results suggest that conscripts who were eating berryvegetable nectar visited less at the hospital clinic and had minor amount of outdoor service reliefs during intervention. These differences were seen while comparing intervention subjects and all controls, but not between intervention subjects and company controls who were living in same barracks.

The results were similar as compared to the earlier study among young skiers, where number of the overall URTIdays and bed days decreased.12 However, there are certain differences between participants in these two studies: while young top level athletes tend to observe their health in detail, current conscripts were sample of Finnish male population. Moreover, in the current study the decisions of service relieves and the hospitalization were done by physician instead of subjective diary as in the case of young skiers. Unfortunately, we did not have specific individual diagnoses and thus we must suppose that an observed alternation in the hospital visits (Figure 1) and in the other endpoint incidences reflects URTI epidemics. In general, epidemic diseases may increase the number of hospital visits. Furthermore, most of hospital visits and missed service days among Finnish conscripts are due to URTI.11 Moreover, time of the study i.e. cold seasons is typical for URTI-epidemics.8

Population immunity13 may potentially explain why significant differences were not observed between intervention subjects and company controls. On other hand, while analyzes were done by company by company, comparison with company controls were done within four companies, and low number of companies potentially limits statistical power.

In the current study, the action mechanisms of the berry-vegetable nectar remains speculative. It has been concluded that vitamin C supplementation may not decrease URTI morbidity,14 but phytophenols may promote health and diminish URTI.4,5,15-19 There are, however, other potential explanations such as supplementation by energy ingredients due to nectar,12 and among young skiers high URTI morbidity was partly explained by great gap between high training load and low nutritional energy intake. Moreover, the post-exhaustion related open window of immunity may be modulated by phytophenols, while phytophenols like tannins decrease the oxidative damage including lipid peroxidation,20,21which might diminish post-exhaustive exercise related low immunity phase.22 However, once ingested, phytophenols may be subjected to extensive metabolization, which may effect on phytophenols affects.23 Correspondingly, our earlier study indicated that rather quercetin than the vitamin C content correlated with their antibacterial activity in vitro. 12 However, while eating phytophenol containing foods as berries, conditions in the mouth and in the upper respiratory tract may become less favourable for pathogenic microbes,4,24 and the prevention of microbial adhesion is one possible mechanism to explain antimicrobial effects by phytophenols.16,17

Staying healthy and being capable to exercise have importance during military service. On other hand, the effects of URTI on public health may have high relevance. Military environment may work as a potential melting pot for URTI-microbes when conscripts gather to do their military service. Correspondingly, while these conscripts return among civilians using public transport, more viral version of URTI may be passed back to infect civilians. Total economic effects of URTI are significant due to lost in school and workdays and medical costs.25

The current study has strengths such as an objective and the blinded recording of health incidences. Moreover, military system offers some unique advantages for a science, such as high number of participants who are living in similar environment, who do similar exercise, and who had similar diet ad libitum. This kind of circumstances may be difficult to organize elsewhere. On other hand, because of military systems and habits, we did not got the more specific data of individual health such as URTI-related diagnoses. Therefore, we were forced to perform analysis between companies, which diminished statistical power and refers that our results are rather suggestive.

Our results suggest that the nutritional supplementation by berry-vegetable nectar may possess health promoting potential; subjects with berry-vegetable nectar supplementation had lower number of visits at hospital clinic and the minor amount of releases from military outdoor service during URTI epidemics as compared to controls. However, additional studies with more specific data are needed to confirm the results.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and the authors declare that these experiments comply with current Finnish laws. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Northern Savo. All subjects gave informed written consent. These results have not been published elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We get donation of the berry-vegetable nectar by Lieksan Laatuherkut OY (Lieksa, Finland, Europe). Moreover, collaboration with servicemen and personnel of the Garrison of Vekaranjarvi, Tuohikotti, Finland are highly appreciated.