INTRODUCTION

Argon plasma coagulation (APC) is a non-contact form of electrosurgery that utilizes ionized argon. Ionized argon is called as plasma. The argon gas, in the presence of a highvoltage electrical field, is ionized and creating a monopolar current conducted by the plasma to the target tissue. Heat energy produced by this process causes the tissue coagulation or hemostasis. The heat evaporates intracellular and extracellular water and denatures proteins, producing the coagulative and destructive effects on tissue.1 This technique was first used with gastrointestinal endoscopy using a flexible probe in the early 1990’s and was used mainly as a modality for hemostasis during polypectomy.2 Subsequently, it has also been used in otolaryngology and dermatology.3,4 More recently, APC has been successfully used during bronchoscopic procedures to debulk malignant airway tumours, control hemoptysis, remove granulation tissue from stents or anastomoses, and treat a variety of other benign disorders.5-9 Pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, airway fire, and burned bronchoscope are complications of APC. However, these complications are reported in less than 1% of the all cases.5

This report describes a case of very rare complication of APC (concomitant secondary pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema) following an attempt to relief airway obstruction caused by a malignant lung tumour.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old male was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital. He was suffering from stage 4 squamous cell lung cancer diagnosed approximately 2 years ago. The patient had a history of chemotherapy with cisplatinum and gemcitabine for 4 cycles which was followed by 4 cycles of Pemetrexed because of cancer progression. Following this, the diasese again progressed and the patient started treatment with oral erlotinib (150 mg/day). From that time, dyspnea remained as a leading symptom although the patient’s general clinical condition was better. He was referred to the local medical council and APC was offered to him in order to reduce dyspnea. He was informed about the procedure and informed written consent form obtained. The patient tolerated the procedure well and consistently experienced relief of his obstructive symptoms. He was followed for 24 hours without any significant complication. Then, he was discharged from hospital and was advised follow-up in outpatient clinic. Three days after the APC procedure, patient presented to us with 10 hours of swelling of the neck and face.

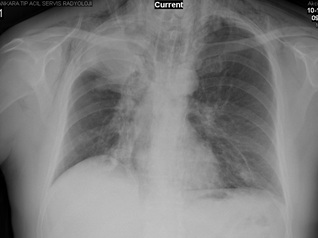

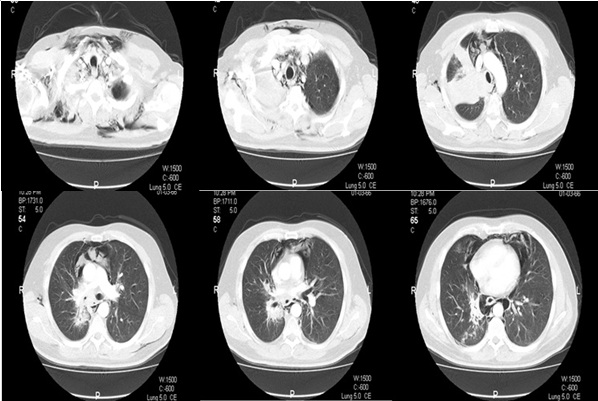

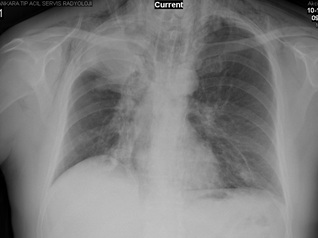

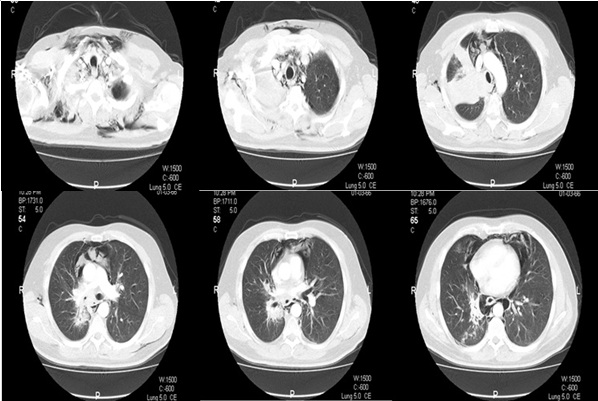

On examination, blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg and electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia with a rate of about 120 beats/minute. Examination of the chest revealed diminished breath sounds in the upper zone of the right lung. There were crepitus on both sides of neck. Hemogram and results of blood chemistry were within normal limits. Measurement of arterial blood gas analysis on room air revealed pH: 7.44, PaCO2 : 34 mmHg, PaO2 : 63 mmHg, HCO3 – : 24 mmol/L and SaO2 : 92%, compatible with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Chest radiograph findings included a homogenous and regularly-shaped dense shadow with volume loss of the right upper lobe, presence of air in the subcutaneous tissues of the neck region, and linear air shadows along the borders of trachea (Figure 1). Thus, he underwent computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and neck. CT images revealed the presence of air trapping in the mediastinum and subcutaneous tissues which confirmed the prediagnosis of pneumomediastium concomitant with subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2). There was no sign of a pneumothorax.

Figure 1: Chest radiograph of the patient on admission.

Figure 2: Thorax CT images of the patient on admission.

The patient was hospitalized, and nasal oxygen therapy was administered during the bed rest. He was discharged on the 5th day of follow-up as his complaints disappeared. He continues to cope with symptoms of lung malignancy. He is free of all previous symptoms related to APC procedure and has no sign of a relapse.

DISCUSSION

Pneumomediastinum is the presence of air within the confines of mediastinal structures which originates from the alveolar space or conducting airways.10 This entity was first described by Laennec in 1819.11

Pneumomediastium is divided into two subtypes based on etiology: spontaneous (primary) and secondary.12 Primary pneumomediastinum is a rare medical condition without any apparent predisposing factor or disease. On the other side, the presence of air in the mediastinum is considered as secondary pneumomediastinum when a causative factor is identified, such as penetrating or blunt trauma to the chest, forceful vomiting (Boerhaave’s syndrome), medical procedures such as bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy, esophageal and tracheobronchial rupture, and dental procedures. Besides, some studies reported usage of cocaine and marijuana, and the presence of asthma (usage of bronchodilators) as the secondary causes of pneumomediastinum. In this case the cause of the pneumomediastinum was flexible bronchoscopy performed for APC.

The pathophysiology of pneumomediastinum was described by Macklin and Macklin based on the results of an animal study.13 According to their explanation, following the terminal alveolar rupture (primary pathology), alveolar air passes through the perivascular interstitial tissue towards the hilum. Then, it reaches mediastinum and is being trapped among the mediastinal structures.

Pneumomediastinum may be complicated with subcutaneous emphysema or pneumothorax in 40-100% of the cases, if intrathoracic air leaks into the adjacent soft tissues.14 In our case it was concomitant with subcutaneous emphysema.

Chest and neck pain, dyspnea, hypotension, dysphagia, subcutaneous emphysema, and cough are the common features. Chest pain is usually retrosternal and may radiate to the neck or into the back. In almost all cases, physical examination reveals no abnormality. Palpable crepitus is only can be detected in patients complicated with subcutaneous emphysema, so it may be absent in half of the patients.14

The high degree of suspicion is very important for the establishment of the diagnosis.15 There is no consensus on the investigation of this disease. Some authors point to the chest radiography (combination of posteroanterior and lateral graphs) as being sufficient in nearly all cases and CT is recommended only in doubtful cases.16,17 However, it should be remembered that chest radiography may be normal on admission and CT is the gold standard in detecting mediastinal air. CT is also accurate in diagnosing tracheobronchial and esophageal ruptures. Electrocardiography may demonstrate non-specific ST segment changes, reduced voltage, and axis deviations in some cases.18 In this case, posteroanterior chest radiography revealed the presence of air shadow suggesting pneumomediastinum and CT was ordered for the correction of the prediagnosis.

The treatment includes bed rest, analgesics if needed and oxygen administration. It is usually benign and nonrecurrent. The patient should be hospitalized for a minimum of 24 h to prevent potential complications. In most cases, secondary pneumomediastinum resolves within several days, as seen in this case. Administration of antibiotics is only recommended in cases presented with signs of an infection or mediastinitis. However, there is also a life-threatening condition called as malignant pneumomediastinum which is characterized by the presence of excess air in the mediastinum. In such cases, subcutaneous aspiration and incisions may be required to evacuate mediastinal air, and if subcutaneous aspiration is not sufficient cervical mediastinotomy should be considered.19

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. No acknowledgement, no financial or material support.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

EO: Concept and Design of the Study; Acquisition of Data; Analysis and Interpretation of Data; Revising the Article Critically For Important Intellectual Content; Final Approval of the Version to Be Published.

MU: Concept and Design of The Study; Acquisition of Data; Analysis And Interpretation of Data; Revising The Article Critically For Important Intellectual Content; Final Approval of the Version to be Published

PC: Concept And Design of the Study; Acquisition of Data; Analysis And Interpretation of Data; Revising The Article Critically For Important Intellectual Content; Final Approval of the Version to be Published.

PK: Concept And Design of the Study; Acquisition of Data; Analysis And Interpretation of Data; Revising the Article Critically For Important Intellectual Content; Final Approval of the Version to be Published.

ZA: Concept and Design of the Study; Acquisition of Data; Analysis and Iinterpretation of Data; Revising The Article Critically For Important Intellectual Content; Final Approval of The Version to be Published.