BACKGROUND

From the possible first ever clinical audits, undertaken by Florence Nightingale during the Crimean war of 1853-1855, to the Codman’s “end result idea” in 1912 on monitoring surgical outcomes audit has come a long way and is now widely accepted as a quality improvement process and practiced within the National Health Service (NHS).1

Department of Health’s (DOHs) White Paper `Working for Patients’ laid down the plans for the need and the planning of the audit.2 Evolution of audit in NHS in its present form, dates back to early 90`s and the first meeting of DOH`s first Clinical Outcome Group (COG) took place in 1992. The aim was to give strategic direction to the clinical rather than merely medical audit. It was the first time when a multidisciplinary team approach was adopted to improve clinical outcomes.3

In 1993, medical audit became clinical, clinicians across the board came together on a common platform to review patient`s clinical outcome. With further availability of resources and funding clinical audit became an accepted norm across the NHS trusts. Clinical audit is now an established part of the NHS landscape and is at the core of a local monitoring system of performance. Clinical audit was originally integrated into clinical governance systems4,5 as one of the seven pillars, and soon after was made a component of Clinical Governance.6,7 It was subsequently embraced by various governing bodies, The Government (our employers), The General Medical Council (GMC) (our regulatory body), our insurers (Medical Protection Society (MPS), Medical Defense Union (MDU), etc.) and our respective professional bodies.

The NHS Plan8 further gave these policies impetus and introduced proposals for mandatory participation by all doctors in clinical audit and developments to support the involvement of other staff, including nurses, midwives, therapists and other NHS staff.

This study was conducted to identify the trends among trainees in NHS, their participation and awareness about clinical audit. We also wanted to identify areas of improvement in audit activity among trainees in UK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was carried out in accordance with UK clinical governance guidelines. Doctors ranging from F1 to ST5 level from ten hospitals in UK participated by completing online questionnaires or hand written forms. Seventy-five percent (n=75, 75%) completed questionnaires were returned.

RESULTS

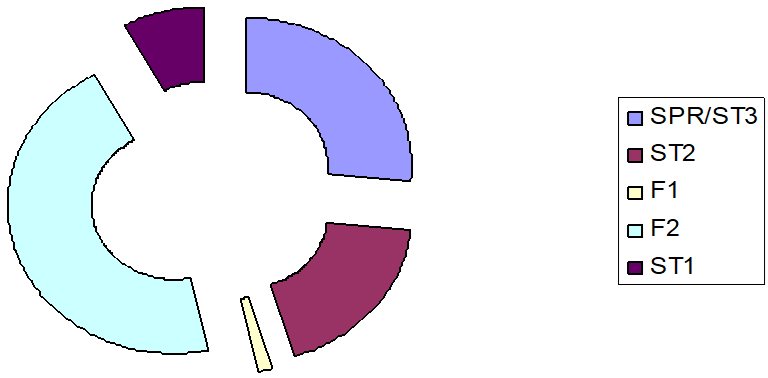

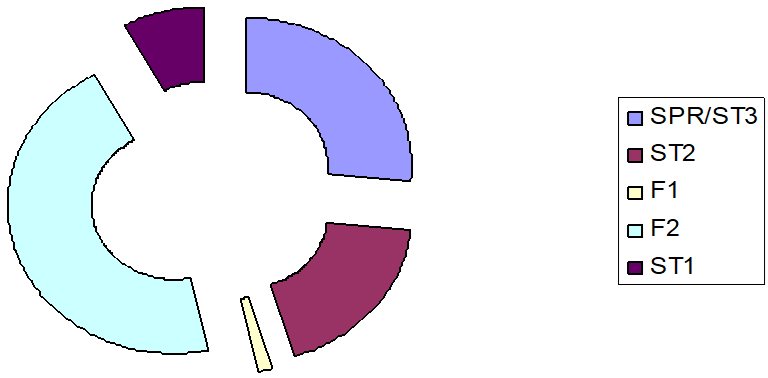

Among those 75 responses, 1(1.33%) was from F1, 34(45%) were from F2s, 6(8%) were from ST1, 14(18.66%) were from ST2, and 20(26%) were from ST3-5s and post-basic training fellows (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Responses from training fellows.

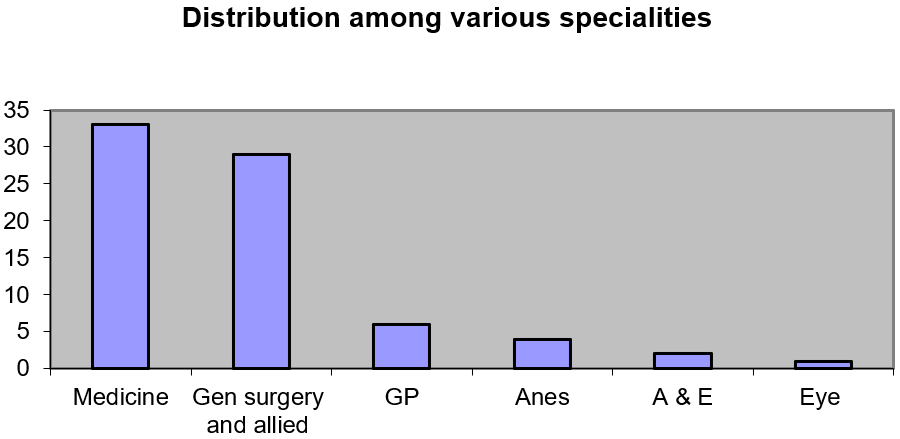

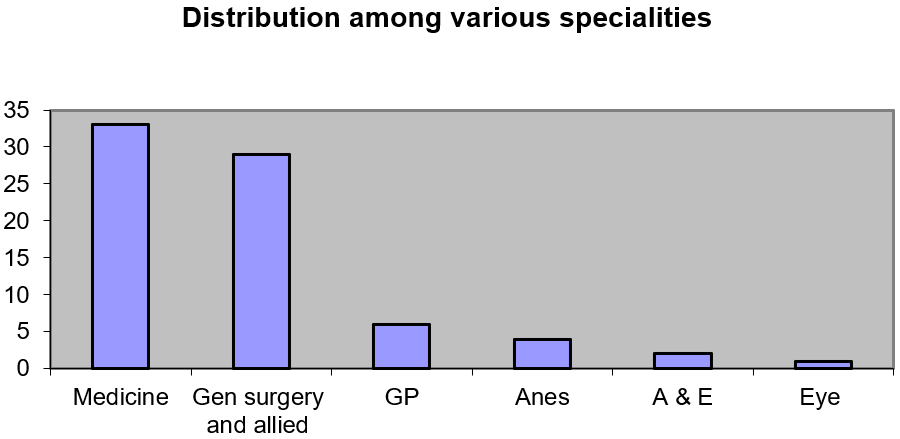

33(44%) respondents were from medicine, 29(38%) from General surgery and allied Specialities, 6(8%) from GP rotation, 4(5.3%) from anaesthesia, 2(2.6%) from A&E and 1(1.33%) from ophthalmology (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution among various specialities.

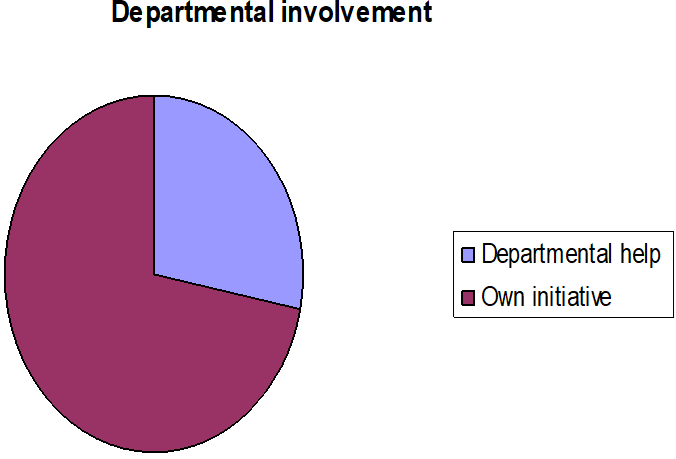

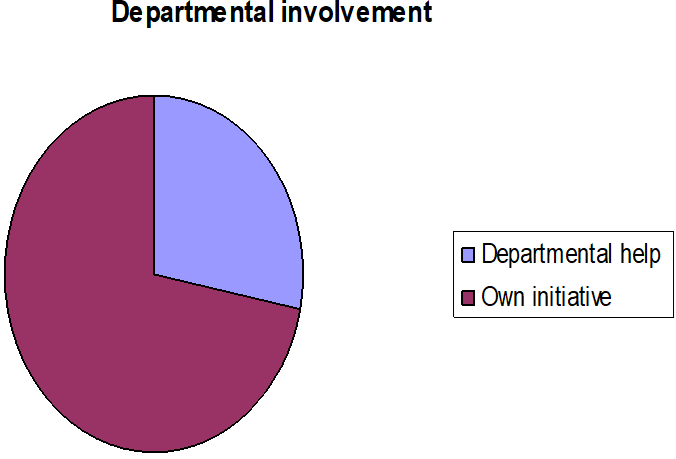

About 70 respondents (93.3%) had been involved in audit in last 12 months of their job across all the Specialities. Most (54, 72%) of the respondents did audit on their own initiative and only about one fourth of them were motivated by others (n=21, 28%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Involvement of various specialities

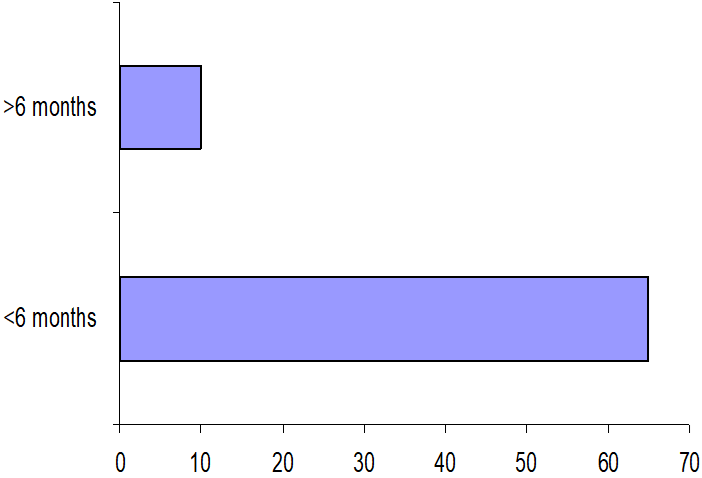

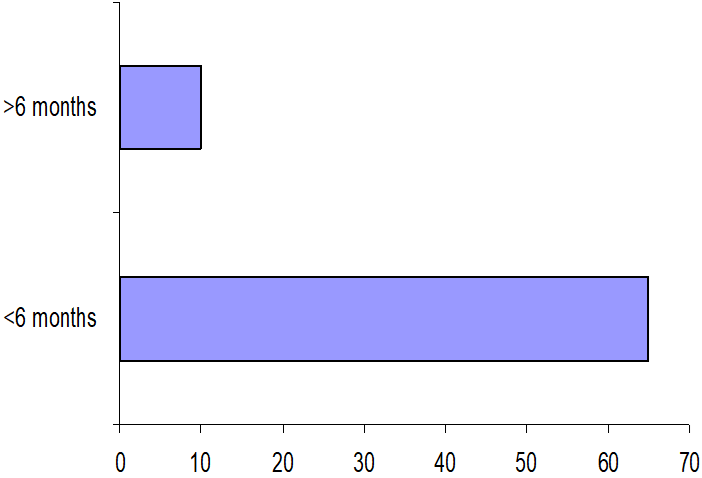

Eighty six percent (65) of the respondents completed their audit within six months (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Completion of audit

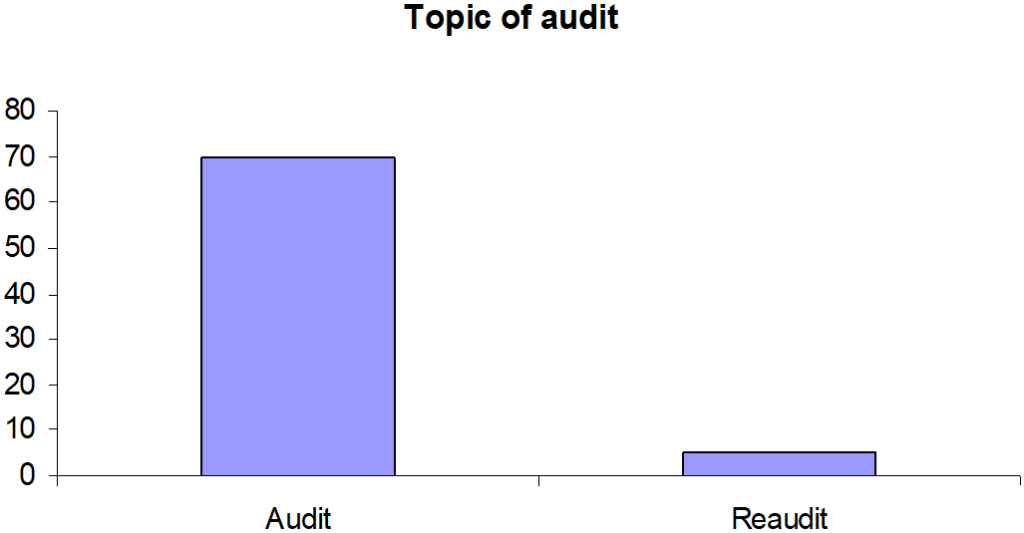

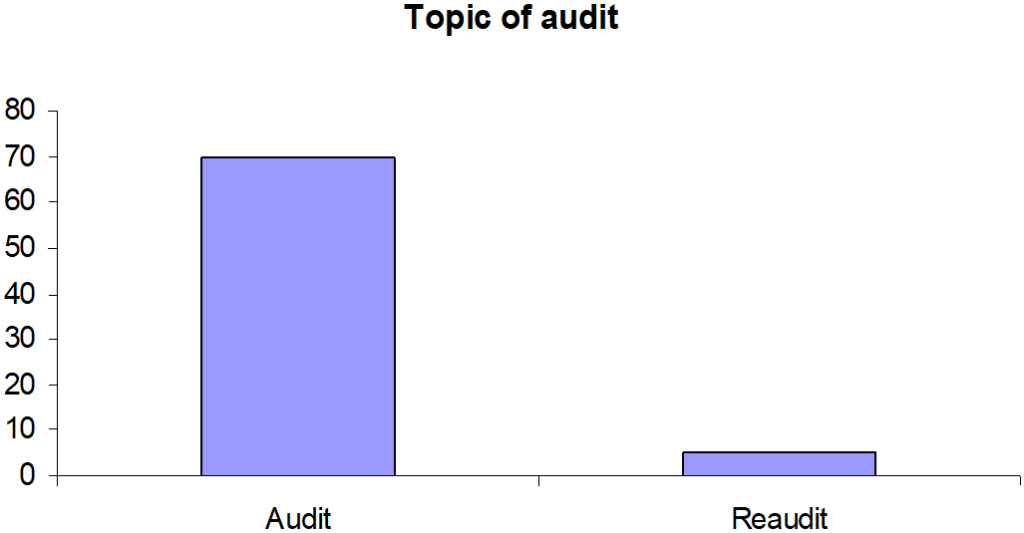

Only 6.66% (n=5) of the audit topics were related to the re-audit part of the audit loop (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Topics were related to the re-audit.

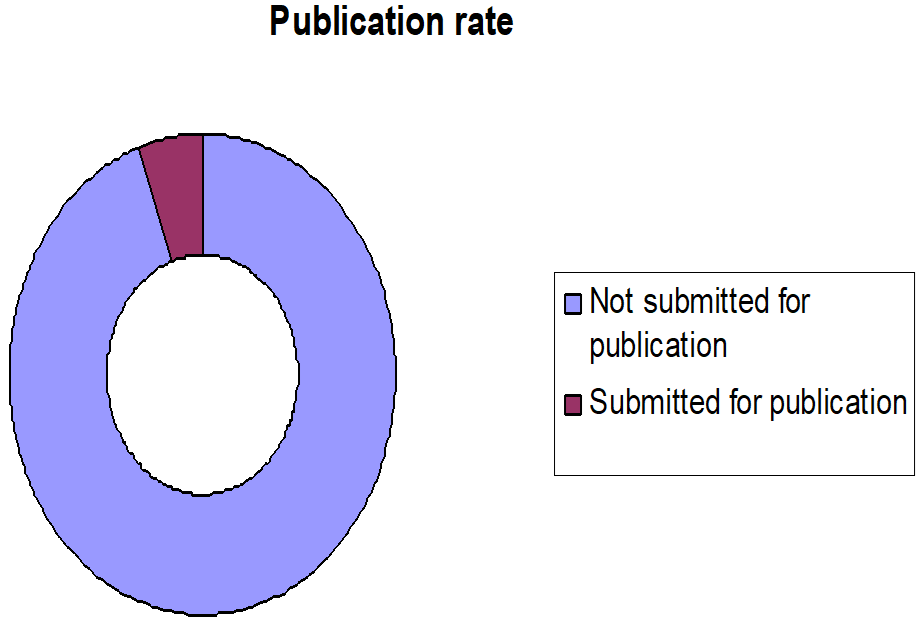

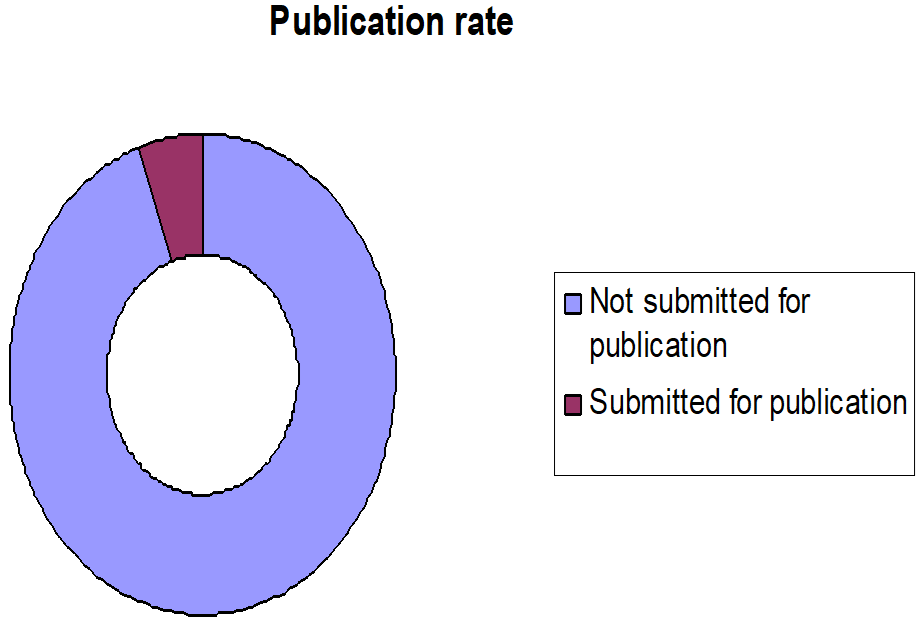

Only four respondents (5.33%) manage to submit it for publication (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Publication rate

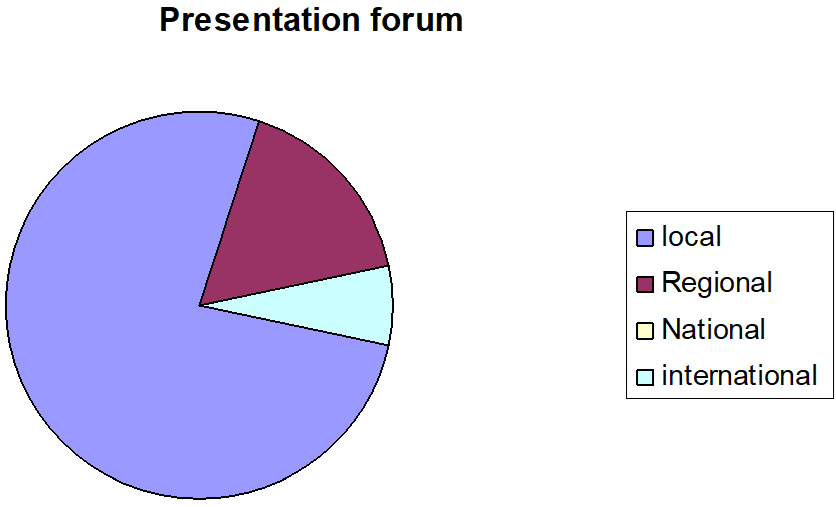

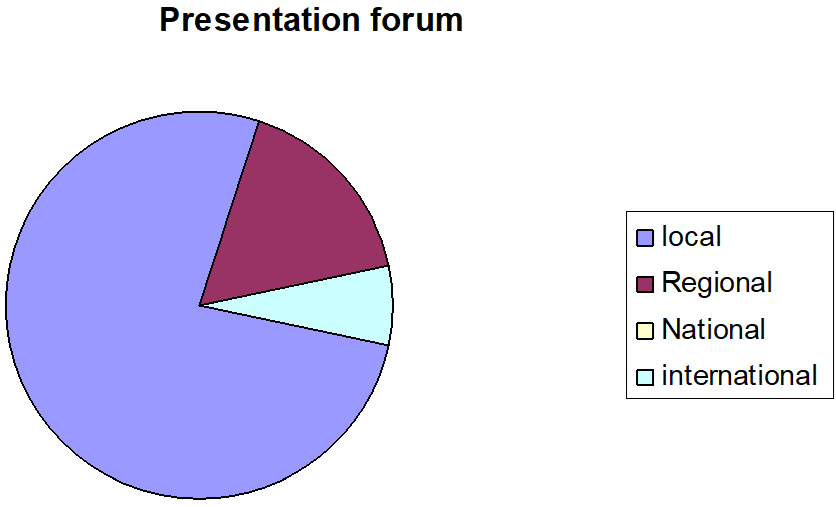

Most of the audits (n=60, 80%) were presented at a local (n=46, 76.66%), regional (n=10, 16.66%) international (n=4, 6.66%) and none of the audits were presented on national forum (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Presentation of different forums.

Most of the audits were focused on local practices within their own institution (n=71, 96%) and only 4% of the respondents were involved in regional and national audits. Very few respondents (1.3%) were using advanced statistical software like Statistics is a software package used for statistical analysis (SPSS) and Parameter-related Internal Standard Method (PRISM).

DISCUSSION

Audit has always been considered as a key component in improving medical education and training. It has been suggested as a vital part of emergency medical education.9

Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) or European Working Time Directives (EWTD) in conjunction has lead to shorter training period, wanting people short of time to do academic/clinical governance activities. However, undertaking such activities is always beneficial and leaves a person with reflective education.

It cannot be overemphasized the importance of audit activity in clinical career and the same can be achieved by simple audit exercises better methods and appropriate guidance.10

Medical trainees have always been questioning about the educational value of audit activity and it creates subconscious resentments towards fulfilling audit activity and the same impression is carried on as being a consultant and thereby undermining the clinical significance of audit activity.11

We are already aware of the fact that most of the trainee doctors are involved in audit activities but the need to have better education and training about audit practices has been emphasized time and time again.12 Vast majority of clinical audits conducted by junior doctors don’t have significant clinical impact in terms of change of practice purely due to wont of quality of conducted audit and inadequate skilled clinical supervision.12

Nettleton J et al have reported experience of 146 junior doctor’s across 21 Specialities about clinical audit and have suggested that although enthusiasm was abundant, however falling short of core knowledge and methodology of audit and therefore failing to have robust framework for undertaking effective audit for a meaningful result which may reflect in change of clinical practice.13

Karran et al in 1993 have reviewed the perception of general surgical staff within the Wessex region of the status of quality assurance and surgical audit and they inferred that majority of registrars (86%) agreed the importance of collection of relevant, accurate and complete clinical outcome.14 However, 56% among them realized that that the primary objectives were not met. The reply from the consultants was in agreement with meeting meaningful surgical audit and quality assurance, which should be ideally critically peer reviewed.14 Brazil et al have looked into audit as a learning tool in postgraduate emergency medicine training.9

Our study suggests that re-audits were rarely carried out, causing audit cycles to be incomplete. We have also identified that we need to encourage the trainees to use the latest available statistical software’s, so that they can appreciate the value of having scientifically robust approach and to be in a better position to critically appraise any recent advancements in our profession. Most of the junior doctors are motivated to do the audit on their own initiative but we need to better educate them in all aspects of auditing practices including presentation of audit results at national level and to encourage them to publish it. Better education will ensure that audits produce useful recommendations to further improve clinical governance. Early cultivation of good auditing practices is particularly important amongst junior doctors so that they in turn can educate their juniors as their careers progress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to all the trainee doctors who have responded to the questionnaires.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.