INTRODUCTION

The open approach to radical and partial nephrectomy remains a commonly practiced procedure despite considerable advances in minimally invasive surgery. Renal surgery may be associated with severe and prolonged post-operative pain. A multimodal approach to analgesia has been shown to be beneficial as part of enhanced recovery protocols.1 Epidurals have traditionally been core in providing post-operative analgesia to this patient cohort. Whilst epidurals still have a clear role in certain patient groups there has been a shift away from their routine use across many types of major surgery, with the acknowledgement that there is a less definitive mortality benefit than previously accepted.2 The 3rd National Audit Project from the Royal College of Anaesthetists demonstrated that whilst overall serious complications following central neuro-axial blockade were low, the majority occurred in the peri-operative setting as opposed to obstetric or chronic pain environments.3 Adverse events associated with epidural use can be divided into procedural risks at insertion, and consequences of administered medication. Epidural opioids are often combined with local anaesthetic solutions for infusion via epidural catheter and can lead to side effects such as nausea, vomiting, pruritus and respiratory depression.4 These concerns have led to increased interest in novel analgesic strategies with comparative analgesic properties but potentially fewer side effects.

The infusion of local anaesthetic into the surgical wound has been shown to be a simple, safe procedure that results in comparable analgesia to that provided by epidural, with favourable side effect profiles.5,6 Meta-analysis examining novel local anaesthetic wound infiltration in patients undergoing colorectal surgery concluded that these techniques reduced pain scores, reduced opiate requirements and increased recovery indices compared with placebo or routine analgesia.7 Similar benefits have been demonstrated in open abdominal vascular surgery,8 open hepatic surgery9 and open nephrectomise.6,10

The pilot study aims to assess feasibility of a randomised control trial comparing continuous wound infusion (CWI) plus patient controlled analgesia (PCA) to conventional analgesic approach via epidural for open renal surgery. Objectives included estimation of necessary recruitment rates, testing appropriateness of outcome measures, estimation of procedural failure rates, incidence of respiratory and gastrointestinal complications and use data to refine the randomised control trial design.

METHODS

Ethical approval was received from the National Research Ethics Committee (South West, 13/SW/0160). This pilot study was designed to test the feasibility of collecting specific outcome data pertaining to the two aforementioned analgesic strategies, epidural analgesia and continuous local anaesthetic infiltration via wound catheter plus patient controlled analgesia for patients undergoing open renal surgery.

Patients were identified by the clinical team and once verbally informed about the study, were given written information and opportunity to discuss the project with a team member. Fully informed patients were invited to participate in the trial, and written consent was obtained. Participants were block randomised by a team member, independent to the data acquisition and analysis process, using the Stats Direct v3.1 (Altrincham, UK) statistical software package and randomisation function.

Male and female adult patients requiring open renal surgery were included in the study. Radical nephrectomy was approached via a loin incision and transperitoneal approach. Extraperitoneal access was used for the partial nephrectomies. Exclusion criteria included patients unsuitable for an epidural (localised skin sepsis at proposed site of injection, coagulopathy), unsuitable for a CWI catheter and those listed for laparoscopic surgery.

Both patient groups received a standardised anaesthetic as per the study protocol. Arterial and central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring were established as clinically indicated. At induction, patients were administered Midazolam 2 mg, Propofol 2-3 mg/kg, Remifentanil and Atracurium 0.5 mg/kg. Intermittent positive pressure ventilation was commenced with an FiO2 of 0.6 to 0.7 and Isoflurane at 0.7-1.0 monitored anesthesia care (MAC) for anaesthetic maintenance. A remifentanil infusion (50 mcg/ml) was initiated. Patients were administered 1 to 3 litres of crystalloid intra-operatively with boluses as required. Post-operative fluid administration was guided by clinical indication. Those undergoing partial nephrectomies received intraoperative Mannitol 0.5 g/kg. All patients received Cyclizine 50 mg and Ondansetron 4 mg intra-operatively and further antiemetic as required. Patients received intravenous morphine boluses in recovery, if required, followed by regular Paracetamol 1 g 6-hourly and Tramadol 50-100 mg 6-hourly if required. Patients in the CWI group all received patient controlled analgesia (PCA). Patients in the epidural arm received opioid within the standard epidural bag mix, and therefore did not have a PCA.

For those randomised to the CWI group, a wound infiltration catheter was inserted at the end of surgery. Partial nephrectomies received a 15 cm Baxter painfusor catheter and total nephrectomies received a 22.5 cm Baxter painfusor catheter. The surgeon inserted the catheter into the deep wound space and flushed with 1 ml of 0.25% Bupivacaine to check catheter integrity. The catheter was inserted through an introducer needle, approximately 7 cm from one end of the incision and placed along the full length of the wound. The entry site was chosen to facilitate patient comfort and nursing access and the 7 cm distance was necessary to create an adequate subcutaneous tunnel and avoid leakage of the anaesthetic infusion from the entry point. After insertion, the introducer needle was split and removed. The catheter was positioned after closure of the peritoneum or transverse muscle, being placed between the deep muscle layer and internal oblique. If the deep muscle layer was not robust enough for secure suturing, a tunnel was created with blunt or sharp dissection between the transverse and internus layers. Care was taken to avoid including the catheter in the suture when closing the internal and external oblique layers. Finally, the subcutaneous space and skin were closed. The catheter was threaded and secured with a ‘Lockit’ dressing. These patients received subcutaneous wound infiltration of 29 mls of 0.25% bupivacaine prior to commencement of the CWI. The painfusor then infused 0.25% Bupivacaine at a rate of 5 mls/hour for 96-hours.

In the epidural group, patients had an epidural sited at the appropriate level by the anaesthetist prior to surgery. A test dose was given but the epidural was not subsequently used intra-operatively. At the end of surgery, the epidural was bolused with 0.25% Bupivacaine + 100 mcg Fentanyl (volume) and a standard epidural mix of 0.125% Bupivacaine with Fentanyl 4 mcg/ml was commenced at a rate of 1 to 10 mls/hour. The epidural then stayed in situ for as long as it was deemed necessary.

Primary outcomes evaluated were pain scores (visual analogue pain scores).

Secondary outcomes included intravenous fluid management (administered volumes of intravenous crystalloid, colloid and blood, and total fluid output), hypotensive episodes, patient mobilisation, antiemetic use and evidence of post-operative ileus (presence of clinical features including absent bowel sounds, associated abdominal distention, nausea or vomiting, respiratory morbidity (reduced SpO2, length of hospital stay and patient acceptability as assessed by the Quality of Recovery (QoR-15) questionnaire.11 Demands on medical and nursing care were assessed using the patient’s post-operative observation chart and whether a patient’s deranged physiology had prompted any primary or urgent reviews, having triggered an early warning score, or a medical emergency team (MET) call respectively.

The QoR-15 questionnaire is an 11-point numerical rating scale (0-10) questionnaire for 15 items related to patient function, incorporating dimensions of support, comfort, emotions, physical independence and pain. Patients score function pre- and post-operatively (at 24-hours) for each item.

Data was collected for 25 consecutive eligible patients.

RESULTS

This pilot study included 25 participants; 13 patients in the epidural group and 12 in the CWI group. One CWI patient was excluded due to incomplete data collection. There was a total of 15 males and 9 females with characteristics as per Table 1. Due to the nature of this feasibility trial, the groups were not powered to provide tests of statistical significance, but to inform of a randomised controlled trial. There were no recorded complications from either analgesic technique for any of the 25 patients.

| Table 1. Patient Characteristics for Patients Undergoing Open Nephrectomy, Receiving Analgesia via an Epidural or Wound Catheter. Values Displayed as Mean (SD) or Number (Proportion) |

|

Epidural Group

(n=13)

|

CWI Group

(n=11)

|

| Age (median years) |

72 (8.5) |

59 (13.1) |

| BMI (kg.m-2) |

25.8 (4.2) |

26.6 (4.2) |

| ASA |

| 1 |

2 (15%) |

4 (33%) |

| 2 |

8 (62%) |

4 (33%) |

| 3 |

3 (23%) |

4 (33%) |

| Length of stay (days) |

7.2 (3.8) |

7.2 (4.6) |

| ICU admission |

2 (15.4%) |

5 (42.7%) |

| Haemoglobin (mean) |

| Pre-operative (g.L-1) |

133.9 (15.1) |

126.4 (18.0) |

| Post-operative (g.L-1) |

102.5 (18.7) |

109.1 (15.2) |

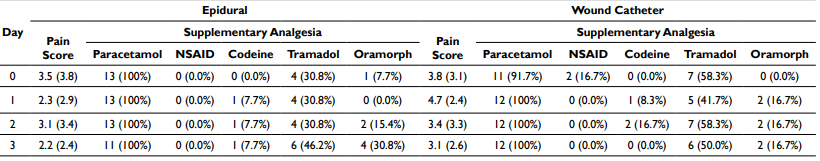

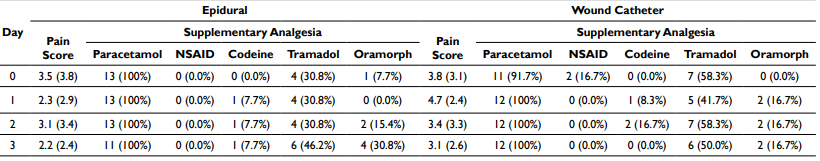

Pain scores (Table 2) were similar for both groups. Marginally higher mean scores are noted for the wound infiltration group on post-operative days one and three. Administration of additional supplementary analgesia had comparable rates for both groups, with tramadol use being higher in the wound infiltration group.

Table 2. Mean Maximal Pain Scores and Supplementary Analgesia. Values Displayed as Means (SD) and Frequencies (Proportions)

Mean blood pressure in both groups was comparable apart from day one, when the mean systolic blood pressure was 19 mmHg lower in the epidural group and below 90 mmHg systolic. The highest mean systolic pressure was on day 3 in the epidural group at 149/79 mmHg. The differences of upper and lower systolic blood pressure between two groups were otherwise within a 10 mmHg range. Mean diastolic values were within 10 mmHg for both groups on all days.

Fluid balance analysis (Table 3) demonstrated similar values for both groups on days 0, 1 and 2. On day three the wound catheter group had a positive net fluid balance of 478.2 ml. Intravenous fluid administration was of greater volume (more than 3000 ml) in the wound catheter group on days 0 and day 3. The epidural group received larger volumes (more than 3000 ml)of fluid on days 1 and 2.

| Table 3. Patient Mobility. Values Displayed as Frequencies (Percentage) |

| Day |

Epidural |

Wound Catheter |

| Total Fluid In |

Total Fluid Out |

Fluid Balance |

Total Fluid In |

Total Fluid Out |

Fluid Balance |

| 0 |

4807.3 (907.2) |

1260.5 (752.5) |

3547.7 (781.0) |

6539.2 (1903.3) |

1130.4 (793.6) |

3929.3 (1764.0) |

| 1 |

3532,2 (1798.4) |

2073.7 (1046.6) |

1384.9 (1899.9) |

2831.4 (782.9) |

1980.3 (1207.3) |

1046.1 (1334.6) |

| 2 |

3106.5 (1041.5) |

2756.8 (1305.6) |

369.0 (1197.6) |

2657.8 (1272.2) |

2802.6 (1028.9) |

60.3 (1076.9) |

| 3 |

2484.6 (1225.6) |

2732.7 (1390.6) |

-163.1 (1386.0) |

3143.6 (1171.3) |

1908.4 (1200.4) |

478.2 (1799.3) |

Table 4 shows the comparisons of number of patients sitting out and subsequently mobilising for each post-operative day. This showed an overall broad agreement between the two groups, however there was a tendency for more patients to sit out and mobilise at an earlier point in their post-operative period within the wound infiltration group.

| Table 4. Patient Mobility. Values Displayed as Frequencies (Percentage) |

| Day |

Epidural |

Wound Catheter |

| Sat Out |

Walked |

Sat Out |

Walked |

| 0 |

1 (7.7%) |

1 (7.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| 1 |

7 (53.8%) |

3 (23.1%) |

9 (75.0%) |

4 (33.3%) |

| 2 |

11 (84.6%) |

6 (46.2%) |

10 (83.3%) |

9 (75.0%) |

| 3 |

11 (84.6%) |

10 (76.9%) |

10 (83.3%) |

10 (83.3%) |

Antiemetic use was higher in the CWI group, particularly on days two and three. On the third day three, 33.3% of CWI patients were still using one or more antiemetics compared to 15.4% of the epidural patients. More patients in the wound catheter group experienced post-operative ileus, with 50% of patients still experiencing symptoms on day three, compared to 38.5% patients in the epidural group.

No medical emergency team (MET) calls were required for either the CWI or epidural groups. post-operative early warning score (EWS), which would require the patient to have a timely medical review, were slightly higher for the epidural group on days two and three. The frequency of anaesthetic review was higher in the epidural group.

The quality of recovery 15 (QOR-15) (Appendix 1) highlighted that scores had baseline similarity indicating that the randomisation process was effective, and groups were evenly matched.Lower scores were given post-operatively for both epidural and wound catheter groups across all variables. Moderate and severe pain, nausea and vomiting and feelings of sadness or depression were higher in the epidural group compared to the wound catheter group 24-hours post-operatively.

Resource costs were assessed to inform health economics. CWI consumables were more expensive consumables at £73.25 per patient compared with epidurals at £20.15. The cost of the drug was in addition to this.

DISCUSSION

This study builds upon previous research investigating local anaesthetic use via wound catheter infiltration as part of a multimodal analgesic strategy in open renal surgery. It is not possible to draw any conclusions from the data due to the study being a pilot however, it does allow for a descriptive analysis of each group to be reported and also for assessment of the trial protocol thus informing the design of a future appropriately powered randomised control trial.

Due to the reduced patient numbers, numbers the groups were not matched, with patients in the epidural arm having a greater median age. Both groups had a similar body mass index. There was no discernible difference in mean length of stay for the two groups suggesting wound catheter use did not have a detrimental effect on discharge time due to suboptimal analgesia. A higher proportion of patients in the wound catheter group were admitted to intensive care post-operatively because of premorbid comorbidities or intraoperative complications rather than post-operatively from the ward, where analgesic technique could have contributed to the clinical course.

Intravenous fluid administration and balance results were unexpected. It was anticipated that fluid administration for the epidural group would have been significantly larger than the wound catheter group. However, the wound catheter group received comparatively more fluid on day 0, less on days 1 and 2 and more again on day 3. It is accepted that differences may occur post-operatively due to variation in clinician practice.

Safety data for both groups demonstrated similar mean early warning scores for day 0 and marginally higher values for the epidural groups at day 1-3. Similarly, there were no medical emergency calls for patients within the CWI group throughout the study compared to a mean of less than 1 for patients in the epidural group suggesting that the CWI technique was indeed safe and in this small cohort suggested a tendency to a lower rate of post-operative adverse events compared to the epidural group.

Analysis of mobility between the two groups suggested that a greater proportion of patients in the wound infiltration group had sat out by day 1 and walked by day 2, but rates were broadly similar by day 3. Pre-operatively, the patient information leaflet stated that ‘part of the outcome was to test whether these techniques may be better than the other, not just in terms of pain relief, but also the ability for you to move around after your operation’. This is unlikely to have led to any bias in motivating patients in one analgesic group to mobilise earlier than the other.

Antiemetic use was higher in the CWI group. All patients that were in the CWI group concurrently had a morphine PCA device and it may be that the addition of opioid led to higher rates of nausea and vomiting. In a repeat study, the use of plain epidurals and concurrent PCA analgesia could be considered and be more directly comparable. The standard practice in our institution; however, is to use epidurals pre-mixed with opioids, and therefore, a decision was taken to test the novel CWI technique with our established standard of care.

The QOR survey used is a validated tool used to assess pre and post-operative function. It is however validated for use in day case patients and therefore has limited impact in our study. A similar survey, looking at longer-term function in addition to the immediate post-operative period, would be preferential in a future trial. This would be informative when looking at the items ‘looking after personal hygiene’ and ‘communication with family and friends’, which scored low values immediately post-operatively. Moderate and severe pain scores, nausea, vomiting and feelings of sadness or depression all scored higher in the epidural group; this would be interesting to explore in further detail with larger case numbers, over a longer period.

The study demonstrated that recruitment of patients in a larger scale randomised control trial might be challenging due to change in urological practice. During the study ‘robotically-assisted minimally invasive surgery’ was introduced at our institution resulting in a reduction in the number of open procedures, thus limiting otherwise eligible patients to participate. Despite this, the open approach for nephrectomy still has a place in certain clinical circumstances and as such, continuous infiltration of local anaesthetic via wound catheter has the potential to provide a useful alternative to epidural analgesia in these cases.

Strengths of this study include demonstration of the safety profile of the CWI and the large quantity of data collected that could inform future research design. Specific weaknesses include lack a suboptimal matching of patients, due to small number recruited, and that the use of PCA with the CWI may have confounding effects on primary outcome. Also, a QOR tailored to major surgery and the more protracted post-operative period would be more suitable and potentially capture useful differences.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this pilot study suggests that collecting relevant outcome data for an appropriately powered randomised controlled trial is feasible. Recruitment was more challenging than anticipated due to the increase in minimally invasive nephrectomies being undertaken and consideration of a multicentre study may be warranted. A large quantity of heterogeneous variables was collected for this study and in planning for a formal randomised controlled trial, a few of these key variables would have to be chosen to formulate appropriate metrics to answer the research question. This study has suggested that the two studied analgesic techniques are broadly comparable in terms of efficacy and time to discharge, which is useful in terms of CWI not being inferior. It does, however, have implications in planning an adequately powered randomised controlled trial, which would need to be run over multiple centres in order to recruit the necessary volume of patients. The CWI technique potentially presents safety advantages such as ease of siting and not requiring the same level of nursing expertise to look after the patient in the post-operative period, compared to epidural analgesia.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.