INTRODUCTION

The Women’s Health Movement began in the 1960’s with the primary focus of advocating women’s rights to sexual and reproductive health. By the end of the 1990s, a dedicated international journal, Journal of Women’s Health (New Rochelle, NY, USA), focused on women’s health, promoting a greater engagement by women in clinical trials.1 There is now a greater focus on understanding women’s healthcare needs in the context of their social environment as a reflection of their own life priorities, financial circumstances and family responsibilities. Women engage differently with healthcare provision compared to men, which may contribute to why on average, women live longer than men.2,3 Other factors that contribute to the relative longevity of women may include healthier lifestyles than men or because female physiology confers an innate survival benefit. For example, circulating estrogens have a cardio-protective effect through the reduction of blood pressure.4 Even though women have a longer life expectancy than in previous generations, this is not always reflected in an improved quality of life; in fact, the health outcomes at women of greater age have begun to decline over recent decades with an increase in affluence-associated health issues such as obesity, cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes (T2D).5,6

Chronic conditions, which significantly undermine an individual’s quality of life can be even more deleterious when healthcare provision for a society is unmet.7 No country is exempt from these issues. The United States is the largest economy in World, but a significant subset of the population has unmet healthcare needs due to the lack of affordable health insurance for the less affluent. Malaysia has one of the best healthcare systems in South East Asia, but there are still concerns about equity and accessibility for vulnerable groups, particularly for those who reside in suburban or rural areas.8 Such issues are well-documented globally for women who live in non-urban areas as compared to their urban counterparts.9,10,11,12

Identifying and addressing inequalities in healthcare access, including gender-based inequalities are central to implementing a good healthcare system.13 However, when issues such as these are debated and legislated for, the voices of women are often not heard. For instance, Malaysian women’s rights, especially in the context of managing the different facets of their own health have gone through cycles of deterioration and improvement over the years.14 Maternal healthcare has improved significantly, but rights over sexual reproductive health and family planning are still being debated because society is becoming progressively more conservative. These political arguments have an impact on society, including a reduced awareness of sexual reproductive health among adolescents. There are constraints on what can be taught in schools, and the protagonists in such arguments are often ill-informed.15 Society’s expectations of women vary across different cultures, and these expectations can often generate onerous pressures, especially on younger women. For example, misinformation can harm women who are struggling with weight issues or who are concerned that their general appearance does not meet a stereotypical ideal.16,17,18

The government of Malaysia is aware of problems in women’s healthcare access, which are compounded by the burden on women in the provision of socio-economic support within their families and the wider local community.19 For example, the increased intake of highly processed foods is associated with the lack of time to prepare and consume homemade meals. Lifestyles, in general, are becoming more sedentary, and often a modest increase in affluence is responsible for a significant increase in sedentary behavior. This decline in physical activity in turn, promotes a rise in the prevalence of hypertension and type II diabetes in the population.20,21 There is limited information about gender differences in health status in Malaysia, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended more focused regional studies to identify and explore women’s health issues and healthcare needs. This will allow us to understand the underlying problems and the feasibility of applying best practices to help address these deficiencies.22,23

This present study aims to understand the healthcare needs of women who reside in urban and non-urban areas of Malaysia and describe the trends in women’s health behaviors focusing on exercise, body image, and health screening choices.

METHOD

Study Population

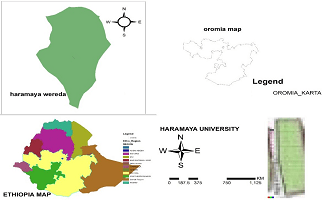

Women residing in semi-urban and rural areas of Kuala Selangor and Sabak Bernam together with women residing in urban localities such as Putrajaya, Selangor and Kuala Lumpur were invited to participate in this study (Figure 1). In total, 1500 women were approached, and of these 1435 (95%) agreed to participate and met our inclusion criteria. All participants were fluent in English or Bahasa Malaysia, 791(55.1%) participants were residents of semi-urban and rural areas, while 644 (45.9%) were from urban areas.

Figure 1. Study Locations in Peninsula (West) Malaysia

Source: from March to September 2018

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Perdana University Institutional Review Board (PUIRBHR0173/174 and PUIRBHR0181). A purposive convenience sampling method was used to recruit potential subjects. The eligibility criteria required individuals to be women who were above 18 or below 45-years of age and able to give informed consent. Data were collected between March to May 2018 and June to September 2018. Participants were given an overview leaflet of the study, and written consent was obtained before the self-administered questionnaire was completed.

Study Tool

The questionnaire gathered information about personal healthcare evaluation, communication with healthcare practitioners, sources of health information, health concerns, weight management, as well as socio-demographic characteristics. The questionnaire was adapted from the Jean Haile’s Women’s Health National Survey 2016 of Australia,24 and translated into Bahasa Malaysia. The adapted questionnaire was divided into eight sections: self-health rating, communication, health information sources, health risk and status, pain experience, weight management, mental health and socio-demographic information.

Data Analysis

Statistical software for social sciences (SPSS) version 23 was used to analyze the data collected. All variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Pearson chi-square was used to evaluate the relationship between variables. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant in all cases. Being overweight or obese was interpreted as an uncontrolled accumulation of adipose tissue that may affect health. In this setting, the WHO body mass index (BMI) classification was utilized in this study. Individual participants were categorized into underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18.5-24.99 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) and obese (BMI>30 kg/m2).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic Factors

Socio-demographic variables were compared between women from urban and non-urban communities (Table 1). The majority of women who responded to this questionnaire from rural/semi-urban and urban locations were from the younger age group. In the rural/ semi urban group (786), 453 (57.6%) respondents were below the age of 25-years while, 487 (84.6%) respondents in the urban group (576) were below the age of 25-years. The ethnicity of the respondents in the urban group broadly reflected the ethnicity of the general Malaysian population, where Malay people represent the majority and people of Chinese descent are the second-largest ethnic group. The proportion respondents with Indian ethnicity were much higher in rural areas at 50.9% (r=-0.167, p<0.01). While younger women are over-represented among respondents from both types of location, there is a significant difference in the marriage rates. Among the urban respondents 68.5% were single while only 27.3% of non-urban respondents were single (r=-0.434, p<0.01). Even though none of the non-urban respondents were over 50-years of age, 21.4% of them were widowed compared to only 1.1% in the urban population. This is a reflection of the cultural practices around marriage in some rural communities, where women marry at a very young age.

| Table 1. Relationship between Demographic Variables and Location of Participants (N=1435) |

|

|

Location of Habitation |

| Rural Urban |

Semi-Urban |

| n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

| Age (years) |

18-25 |

453 |

(57.6) |

487 |

(84.5) |

| 26-45 |

333 |

(42.4) |

89 |

(15.5) |

| Ethnicity |

Malay |

105 |

(13.4) |

342 |

(59.4) |

| Chinese |

77 |

(9.8) |

157 |

(27.3) |

| Indian |

403 |

(51.3) |

55 |

(9.5) |

| Others |

201 |

(25.6) |

22 |

(3.8) |

| Marital Status |

Single |

215 |

(27.4) |

435 |

(75.5) |

| Married |

283 |

(36.0) |

122 |

(21.2) |

| Divorced/Separated |

119 |

(15.1) |

13 |

(2.3) |

| Widowed |

169 |

(21.5) |

6 |

(1.0) |

| Education Level |

Primary/Secondary |

786 |

(100.0) |

232 |

(40.3) |

| Diploma/Cert |

|

|

214 |

(37.2) |

| Degree/Masters |

|

|

130 |

(22.6) |

| Income (RM pcm) |

<3000 |

770 |

(98.0) |

339 |

(58.9) |

| 3001-5000 |

16 |

(2.0) |

140 |

(24.3) |

| 5000 |

0 |

0 |

97 |

(16.8) |

| Number of Children |

1-2 |

0 |

|

320 |

(55.6) |

| 3+ |

786 |

(100.0) |

256 |

(44.4) |

| Total |

|

786 |

|

576 |

|

Women in non-urban areas are less-highly educated, with 100% of respondents finishing education by secondary school level. In comparison, 23.3% of urban respondents are educated to at least degree level. (r=0.585, p<0.01). The more advanced education level of urban respondents is associated with a higher household income. Almost all of the non-urban respondents (98%) had a household income of less than RM 3000 PowerCom (pcm) (720 USD) while 18.6% of urban respondents belonged to households with a monthly income of more than RM 5000 pcm (1,200 USD). There was also a significant difference in the family size of participants in the different groups. Women from urban areas tended to have fewer children compared to women in rural areas. (r=-0.400, p<0.01). In urban areas 256 (44.4%) participants had 3 or more children, while all of the participants from non-urban areas had 3 or more children.

The relationship between location and weight management was evaluated (Table 2). In non-urban areas, 27.4% of women are overweight or obese, while in urban communities, 51.3% are overweight or obese (r=-0.238, p<0.01). Consistent with this, just 17.2% of non-urban women have participated in weight loss programs while 72.8% of urban women have attempt to control their weight by diet, exercise or over-the-counter medications (r=0.696, p<0.01). The majority of urban women (55.7%) do no strenuous exercise over the course of the week while this is the case for 35.9% of non-urban (r=0.670, p<0.01).

| Table 2. Relationship between Location of Habitation and Body Weight Management by the Study Population (N=1,435) |

|

Q1: Weight Loss |

Q2: Body Mass Index |

Q3: Exercise Sessions |

| Yes |

No |

Underweight |

Ideal |

Overweight |

Obese |

Never |

1-2 |

3 Times and above |

| Urban |

n |

572 |

214 |

98 |

285 |

283 |

120 |

438 |

191 |

157 |

| % |

(72.8) |

(27.2) |

(12.4) |

(36.3) |

(36.0) |

(15.3) |

(55.7) |

(24.3) |

(20.0) |

| Rural |

n |

99 |

477 |

151 |

267 |

108 |

50 |

207 |

289 |

80 |

| % |

(17.2) |

(82.8) |

(26.2) |

(46.4) |

(18.8) |

(8.6) |

(35.9) |

(50.2) |

(13.9) |

The health-seeking behaviours between the two groups of women were compared (Table 3). We found that 51.1% of women from non-urban communities were interested in improving their current health status but this dropped to 42.5% among women from urban communities (r=-0.164, p<0.01). This was reflected in routine health clinic attendance, where 64.2% of non-urban women attended regular health checks compared to 54.0% of urban women (r=0.837, p<0.01). Vitamin supplements are the most common complementary therapy used in Malaysia.25 In this study 42.5% of urban women took vitamin supplements compared to 33.3% of non-urban women (r=-0.108, p<0.01).

| Table 3. Location of Habitation versus Personal Healthcare Experiences |

|

Location |

| Rural |

Urban |

| n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

| Q1 : Willingness to Improve Health Status |

| Not willing |

20 |

(2.5) |

45 |

(7.8) |

| Somewhat willing |

364 |

(46.3) |

294 |

(51.0) |

| Very willing |

402 |

(51.1) |

237 |

(41.1) |

| Q2 : Attendance to M-Checkup |

| Yes |

505 |

(64.2) |

311 |

(54.0) |

| No |

281 |

(35.8) |

265 |

(46.0) |

| Q3 : Supplements |

| No supplements |

524 |

(66.7) |

331 |

(57.5) |

| Vitamin supplements |

262 |

(33.3) |

245 |

(42.5) |

| Total |

786 |

|

576 |

|

The study findings concluded the fact that more women’s age, ethnic association, marital status, education level, income and number of children are all significant factors for their well-being. These factors are equally contributing factors in their physical health. However, women are willing to actively improve their health by adhering to health check-ups. All these findings are reflected.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study aimed to evaluate attitudes towards positive health behaviors among women of childbearing age in different socio-economic community in Malaysia. The study revealed that Malaysian women across these communities are willing to engage actively in promoting their well-being, especially those women who reside in rural or semi-urban areas. In recent decades, the Malaysian government has invested in primary care coverage in rural communities as a key facet of the county’s development goals. All women have access to government-managed clinics within five km of their homes and are each equipped to reach out to 15000-20000 patients.26 It is interesting to observe that women in urban communities are less inclined to avail of these primary care facilities with regard to routine check-ups. Decision-making around healthcare needs, may not bee qually divided between the men and women within the household, and this could be dependent on household income27 or the norms of an ethnic group.28,29 Consequently, socio-demographic factors can influence how a woman’s healthcare needs are met. Female empowerment in decision-making around healthcare needs may be restricted due to a lack of socio-economic advancement in some communities.30,31,32

Obesity is an increasing challenge in Malaysia and we observed in our study that there was a significant problem in weight management among our study participants.33 We observed a difference in the prevalence of being obese or overweight between our urban and non-urban participants. Women residing in rural or semi-urban communities were less likely to be obese or overweight than their urban counterparts. The impact of socio-economic factors and cultural identity were also noted in studies of obesity based national health morbidity survey, in particular low-income was associated with obesity, compounding the negative impact on quality-of-life (QoL).34,35 The lower prevalence of obesity and overweight in the non-urban group, was correlated with a somewhat active lifestyle among the non-urban participants, while repeated periods of strenuous activity were more common among urban participants. Urban participants were more likely to be overweight and more likely to attempt to manage their weight somehow. There is an indication that women who do not participate in strenuous physical activity as a weight-loss stratagem may be actively addressing their body weight through other means such as diet. Other studies have found that women in Malaysia often preferred taking weight reduction pharmaceuticals (diet pills), over physical activity.36,37 Our observation that women from rural communities are more interested in improving their health status, but are less likely to take vitamin supplements may be due a number factors such disposable income, a greater belief in traditional interventions or accessibility of pharmacies for non-essential medications.

This study identifies a number of factors that may influence decisions around healthcare engagement by individuals that cause the dichotomy between women in urban and non-urban environments in Malaysia. It may be necessary to develop different, targeted approaches to be effective in different communities to address the problems, such as overweight in younger women that will lead to chronic illnesses in later life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the advice on the statistical analysis provided by Prof Amuthaganesh Mathialagan in support of this project. The authors wish to thank Perdana University – Royal College of Surgeon in Ireland graduates who helped in collecting data at suburban and urban areas in Malaysia: Dr Anderson Yong Zae Szen; Dr Chan Wai Sen; Dr Chua Siaw Fen; Dr Chua Sue Ying; Dr Dhaneersha Nair; Dr Filza Affendi; Dr Kavitha Karnapan; Dr Neoh Seong Kiat; Dr Nurul Ainul Nabiah; Dr Pavitra Gunasekaran; Dr Pua Tze San and Dr Wei Kee Yen.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept (DF, SK), design (DF, SK, WT), definition of intellectual content (SK), literature search (DF, SK, WT), experimental studies (DF,SK), data acquisition (DF, SK), data analysis (SK), statistical analysis (SK), manuscript preparation (DF, SK, WT), manuscript editing (DF, SK, WT) manuscript review (DF, SK, WT) and guarantor (WT).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.