INTRODUCTION

Poliomyelitis is an oro-fecal disease that is easily transmitted in poor sanitation and hygiene environment. The disease mainly affects children under five-years-old. The disease is one of the vaccine preventable diseases. Globally, cases due to wild poliomyelitis virus have decreased by over 99% since 1988, from an estimated 350,000 cases to 33 reported cases in 2018.1 In 2012, the World Health Assembly adopted the Global Vaccine Action Plan with the goal of providing equitable access to vaccines by 2020.2 In April 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) strategic advisory group of experts (SAGE) on immunization stressed that the implementation of immunization in the context of health system strengthening and Universal Health Coverage (UHC) requires increased coordination between the public and the non-governmental (including private) sectors.3 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) role in the health sector has also changed in recent years, and significant emphasis has been placed on NGOs contracts for service delivery.4 In low and middle income countries (LMICs), NGOs play a significant role in financing and providing health care services, and the use of NGOs in advancing public health goals is increasingly common.5 In some areas, NGOs seem to be the best tool for developing essential health services and are part of the strategy to achieve UHC.6 NGOs are uniquely committed to providing health services in sparsely populated areas globally, mainly through their active participation in providing health services directly through the ancillary factors of supply.7 Many governments partnered with NGOs, recognizing their significant and often dominant role in providing health services in LMICs.6 Proponents of formal government interaction with NGOs argue that they operate extensively, even in remote and rural areas, and are more accountable than their public-sector counterparts.5 Despite injecting financial resources into health systems, many counties still face difficulties in progress towards sustainable UHC and did not provide preventive and curative health care services.8 In many LMICs, the challenge of adequate provision of quality care to all who needs it becomes even more apparent, as all available human resources for health (both public and private) are required to achieve this goal. However, it is time to change how we look and think about health issues and health services provision if we want to achieve health attainment and well-being for all.9

The Horn of Africa has a long history of outbreaks of poliomyelitis due to large pockets of children remaining unimmunized, weak surveillance systems in some areas that fail to recognize importations before they take hold, mobile populations that are hard to access, and conflict and insecurity that create inaccessible zones. To ensure that the country stays free from poliomyelitis, it is essential to maintain the momentum to reach every child with poliomyelitis vaccines and to strengthen poliomyelitis surveillance.10 Cases of inequity in access to immunization service continue to exist in the region; it remains for the national governments, communities, civil societies and immunization partners to engage into the drive of universal access to immunization as a cornerstone for health and development in Africa.

In Sudan, the national expanded program of immunization (EPI) services are integrated in primary health care services at facility and community levels. Care providers (medical doctors, medical assistant, health visitors and nutritionists), at facility and community levels represent a backbone for these services as they report vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs), identify and direct non-immunize children to vaccinators and deliver education messages to care-givers.11

Although Sudan has been free from poliomyelitis since 2009,12 Sudan is classified as high-risk country for poliomyelitis as there is difficult to reach many areas in the country because of unrest and conflicts. The influx of refugees from nearby countries is another factor. Low coverage with poliomyelitis vaccine plays also a major role. According to the Sudan multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) that was carried out in 2014,13 Percentage of children age 12-23-months who received the third dose of oral poliomyelitis vaccine 3 (OPV 3) by their first birthday was 65.3%.

In research done to study private sector engagement and its contribution to immunization service delivery and coverage in Sudan, the health system has learned the importance of regulating and licensing private facilities and incorporating them into the immunization program’s decision-making, planning, regular evaluation and supervision system to ensure their compliance with immunization guidelines and the overall quality of services. In moving forward, strategic engagement with the private sector will become more prominent as Sudan transitions out of donors’ financial assistance with its projected income growth.14

Following civil wars in Blue Nile, South Kordofan and Darfur, protracted displacement is widespread in Sudan. Ongoing violence, particularly in Darfur, and disasters, predominantly flooding, also trigger significant new displacement every year. In the first half of 2019, about 29,000 new displacements were recorded, 21,000 by conflict and 8,000 by disasters making the internally displaced people (IDPs) to be 2,072,000.15 A study done in Nayala (South Darfur) to assess the vaccination coverage concluded that “the vaccination coverage in the studied area was low compared to the national coverage”. Efforts to increase vaccination converge and completion of the scheduled plan should focus on addressing concerns of caregivers particularly side effects and strengthening the EPI services in rural areas.16 Moreover, there are 1.2 million refugees and asylum seekers. This indicates a dynamic population that needs to be covered and monitored17 as refugees and IDPs are one of the most vulnerable groups for communicable diseases due to low socio-economic status, poor sanitation and hygiene, and low access to services.

Fifty-five percent (55%) of private health facilities in Sudan (411 out of 752) provide immunization services, with 75% (307 out of 411) are based in Khartoum state and the Darfur region. In 2017, private providers administered about 16% of all third doses of pentavalent (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type (B) vaccines to children. Private health providers contribution in immunization services have especially been critical in filling the gaps in government services in hard-to-reach or conflict-affected areas, among marginalized populations, and thus in reducing inequalities and access to services.14

Thus, assessing the private sector and civil society engagement in delivering poliomyelitis vaccination is a step forward to improve the accessibility of health services among IDPs and irregular settlement in the periphery of urban areas such Khartoum. It is important also to determine the enablers and barriers for the private sector and civil society active engagement in the immunization program.

METHODS

Study Design

In this cross-sectional study we used both quantitative and qualitative methods to identify gaps and to assess the private sector and civil society engagement in the implementation of immunization program especially poliomyelitis vaccination among IDPs and irregular settlement in Khartoum State.

Study Area

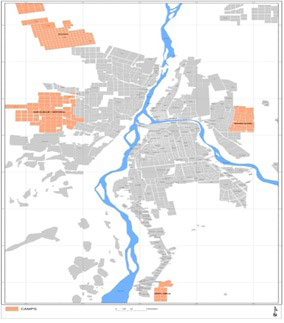

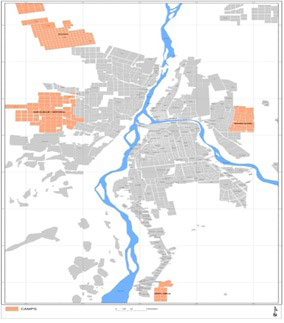

The study area is located in the outskirts of Khartoum. They are distributed over 4 localities out of the 7 localities in Khartoum State (Figure 1). The study covered all the 8 camps and settlements in Khartoum. The study settings included the private and civil society facilities in the camps.

Figure 1. Displaced Camps in Khartoum State-2019

Study Population and Sampling

The study population planned to include one senior facility manger and one EPI service provider at private and civil society’s facilities in the targeted areas. A sample of 30 facilities (15 private clinics/ centers and 15 civil society facilities) had been planned for data collection but we reached 23 of them. The reasons for not including the remaining facilities were: 3 facilities refused to be studied, 2 were closed for maintenance and 2 facilities were visited more than two times and were found closed. In these 23 facilities, 16 managers (3 refused to participate, and 4 were absent during visit time) and 21 EPI service providers (one has no vaccination services and the other the provider was absent) had been interviewed.

Data Collection

For primary data, trained data collectors used a semi-structured interview guideline to interview the managers of private and civil society health facilities at IDPs camps and irregular settlement in Khartoum State. A self-administered questionnaire and review form was used to collect data from the EPI service providers. Data collectors contacted listed participants for permissions and agreement on date and place for interviewing.

Data Analysis

For quantitative variables, the obtained data were coded and then analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 21 and presented in tables. For qualitative part, all data were transcribed verbatim and subsequently translated into english and sent to the qualitative coordinator for initial coding. Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis, paying particular attention to axes of difference, including gender, private center and non-governmental organization. This allowed for an exploration of how and why experiences differ across those axes. The analysis process included coding, sorting and explanation of data, during which links between themes and codes are explored and situated within wider discourses of knowledge about health policies and definition of IDPs. The data coding and emerging themes were discussed regularly.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance: Ethical clearance has been obtained from the national ethical committee at the Federal Ministry of Health on the third of November 2019 and permission from the Khartoum Ministry of Health was also obtained.

Written informed consent: Written informed consent obtained from each participant separately. Consent was documented as a tick on each questionnaire together with signature.

RESULTS

Data obtained through an in-depth interview with 16 managers and self-explanatory questionnaire with 21 EPI services providers at 23 health facilities in the major IDPs camps and the irregular settlement in Khartoum State was presented in Tables 1 and 2. Ten facilities belong to NGOs and the rest were private facilities and both have been established years ago. All mangers were male and 8 of them were medical doctors and all has considerable work experience. Despite that, few were aware about EPI policies, plans and target for immunization (Table 1) and that may explain the findings in Table 5 where the majority of health facilities reported a much higher coverage compared to target. Managers reports that they are willing to have vaccination services and they offer office, furniture and personnel for that. Moreover, they state “we benefit from that. It is a chance to promote for the other services provided at our center” they added “when the mother came to vaccinate her child, she gets to know the center… that is working”. The majority of the managers are not involved in the monitoring process, as they only sign the reports prepared by the service providers.

| Table 1. Characteristics of Health Facilities and their Managers (n=16) |

|

Variable

|

Description |

Frequency |

%

|

| Manger affiliated to |

Private |

9

|

56.3

|

| NGOs |

7

|

43.8

|

| Years since establishment in the current area of work |

Less than 10-years |

7

|

43.8

|

| 10-20-years |

6

|

37.5

|

| More than 20-years |

3

|

18.8

|

| Sex of the mangers |

Male |

16

|

100.0

|

| Female |

0

|

0.0

|

| Age group in years |

<30 |

0

|

0.0

|

| 30-59 |

14

|

87.5

|

| 60 and above |

2

|

12.5

|

| Managers qualification/ specialities |

Medical doctors |

8

|

50.0

|

| Allied health personnel |

3

|

18.8

|

| Others |

5

|

31.3

|

| Managers work experience |

10-years or less |

7

|

43.8

|

| More than 10-years |

9

|

56.3

|

| Managers were aware about EPI policies, plans and targets |

Yes |

3

|

18.8

|

| No |

13

|

81.3

|

Data obtained from EPI service providers through the self-administered questionnaire showed that: 20 were female and the majority was in the age group between 30-59-years and with only basic education (Table 2). Two-third of them reported a work experience less than 10-years. Thirteen of them were vaccination technicians and eight were doing both vaccination and nutrition services at the center. While only 11 (52.4%) of them trained in vaccination, most of participants (95.2%) were trained in communication and health education skills. However, 13 of them reported that the last training was more than 10-years-ago.

| Table 2. Characteristics of EPI Service Providers (n=21) |

|

Variable

|

Description |

Frequency |

%

|

| Age group in years |

Less than 30 |

02 |

09.5

|

| 30-59 |

16

|

76.2

|

| 60 and above |

03

|

14.2

|

| Sex |

Male |

01

|

04.8

|

| Female |

20

|

95.2

|

| Education |

Basic education |

18

|

85.7

|

| University and above |

03 |

14.3

|

| Job title |

Vaccination technicians |

13

|

61.9

|

| Vaccination and nutritionist technicians |

08

|

38.1

|

| Service provider trained in vaccination |

Yes |

11

|

52.4

|

| No |

10

|

47.6

|

| Service provider trained in health education and communication |

Yes |

20

|

95.2

|

| No |

01

|

04.8

|

| Time since last training |

Less than 10-years |

08

|

38.1

|

| 10-years and above |

13

|

61.9

|

| Works only for vaccination and/ or nutrition |

Yes |

13

|

61.9

|

| No |

08

|

38.1

|

| Work experience |

Less than 10-years |

14

|

66.7

|

| 10-years and above |

07

|

33.3

|

Ten of the facilities surveyed offered vaccination services (including poliomyelitis vaccination) on daily basis and 7 more provided the services three times a week. Almost all (95.2%) have an outreach service and 16 (76.2%) served general population as well as displaced population and offering health education services on regular basis at both facility and community level. Twelve facilities (57.1%) have a known catchment area. The majority of health facilities have a contact with the general population in the area but less (only 14, 66.4%) have such contact with displaced people. Twenty (95.2%) facilities perceived that the general population were willingness in vaccination while only 15 (71.4%) have this perception regarding the willingness in vaccination among displaced people. The major gaps in EPI services at facility level include: Lack of awareness (28.6%), the center is far (access issues) from the target population (28.6%), shortage in staff (23.8%), shortage in vaccine supply (14.3%), specified days for immunization are not enough (14.3%), and financial barriers (14.3%), (Table 3).

Table 4 lists the enabling factors and barriers to vaccination services at facility level comparing between general population and displaced people. With exception of the service availability nearby the residential areas, EPI services providers perceived that the general population have a better chance in terms of enabling factors compared with displaced people. Regarding the barriers to vaccination, EPI service providers reported that the barriers were almost the same or slightly different with exceptions of displaced people awareness about consequences of non-vaccination (Table 4). With exception of 3 health facilities in general population and 5 in displaced people, health facilities largely exceeded their assigned monthly target (Table 5).

| Table 4. Enabling Factors and Barriers to Vaccination Services at Facility Level |

|

Variables

|

General Population |

Displaced People |

| Frequency |

% |

Frequency |

%

|

| Enabling Factors |

| Services are available nearby their residence |

13

|

61.9 |

17 |

81.0

|

| They are aware about immunization benefits |

17

|

81.0 |

10 |

47.6

|

| They are aware about the consequence of non-vaccination |

16

|

76.2 |

13 |

61.9

|

| Services are free of charge |

15

|

71.4 |

14 |

66.7

|

| Frequency of services (2 or 3 times per week) |

14

|

66.7 |

11 |

52.4

|

| Staff are welcoming and encouraging |

10

|

47.6 |

7 |

33.

|

| Barriers to vaccination |

|

Too far to reach

|

14 |

66.7 |

14 |

71.4

|

| One has to pay to get services |

12 |

57.1 |

11 |

52.4

|

| Lack of awareness about immunization benefits |

13

|

61.9 |

14 |

66.7

|

| Lack of awareness about the consequences of non-vaccination |

13

|

61.9 |

17 |

81

|

| Limited availability of staff (only one session per week) |

12

|

57.1 |

13 |

66.7

|

|

12

|

57.1 |

11 |

52.4

|

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The health facilities belonging to civil societies and private sector (in areas known as residence for displaced) in Khartoum State provide vaccination services for general population and for displaced people. The managers of these facilities were relatively young (30-50-years) and 50% of them were physicians. The fact that 80% of the managers were not aware of the policies and plans of EPI at state level complies with the finding from Nigeria.18 To reach the target, the experience with other programs showed the need for special efforts to involve frontline managers and staff in health reforms, as well as provision of adequate resources, and an enabling practice environment.19

What is good in the experience of Sudan is that provision of free immunization services is the pre-requisite to be authorized as a primary health centre. The locality health authorities (LHA) asked the center to spare a space with furniture and to nominate a person to be trained by the locality and to be supplied with supplies and equipment such as vaccines on regular basis. The Locality accepts only reports that were signed by the center managers although most of the managers are not involved directly in the vaccination process. This system made immunization unit is more like a delegation from the locality that is settled in those health centers. Although being linked to the locality directly made the communication easier and quicker, but it is obvious that the Ministry of Health (MOH) has to have clear policy towards the private and civil societies health facilities and there should be a special effort to involve frontline managers and staff in health reforms, as well as provision of adequate resources, and an enabling practice environment.18 More involvement of primary health care (PHC) managers in the monitoring process such as being part of coordination committees could ensure the quality of services provided. A study conducted in Asia showed that these coordination committees are important in information sharing and the global alliance for vaccines and immunisation (GAVI) application processes.19

EPI service providers at the surveyed centers were female who were having basic education and with experience of more than 10-years. The last training courses received by the majority were more than 10-years-ago. This calls for giving more attention for continuous professional development as it is found that care providers (medical doctors, medical assistant, health visitors and nutritionists), at facility and community levels represent a backbone for these services.12 Moreover, there is a need for special efforts to involve frontline managers and staff in health reforms, as well as provision of adequate resources, and an enabling practice environment.19 Such special efforts need more engagement from private sector and NGOs.

The Ministry of Health documents revised by the team, showed little attention in displaced people and it seems that no special attention was given to them during planning despite the fact that the majority of children who were not vaccinated were coming from these areas (Ministry of Health reports). Furthermore, the health system profile highlighted that there is a deficiency in the available information about NGOs working in Sudan regarding their plans, budget and distribution. However, they play an important role in filling some of the gaps identified by the government system. Until recently there was no clear national policy towards NGOs and the monitoring and coordination mechanisms were weak.12

In conclusion, the major gaps for vaccination in general and poliomyelitis in particular are low awareness about EPI policies, plans and targets among health facilities managers, low access to EPI services and underestimation of the role of the private and civil societies. This is further complicated by the lack of bad consequences resulted from missing vaccination among displaced people. The Ministry of Health in the State and localities would gain a lot if they adopted a bottom-up approach to ensure primary health facilities manager’s engagement in planning for EPI services in their areas. A clear agreement with a clear mandate for engagement with the private sector and NGOs could add a lot. More attention should also be given to the concept of catchment area as it is become the base for monitoring the progress towards the specified monthly and annual targets for each area.

The private and civil society’s health facilities were not well utilized by EPI program in Khartoum, Sudan to improve the access of people living in areas known as displaced areas to vaccination services. The adoption of a bottom-up approach to engage the private and civil society’s facilities managers in planning for EPI services in their catchment areas is highly needed. A clear mandate for engagement and periodic training for the service providers in private and civil society’s health facilities is highly needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors would like to acknowledge the support provided for this study by the GHD/EMPHNET “EMR Operational Research Studies” The mini-grants funding opportunity.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD (IRB)

Ethical clearance has been obtained from the national ethical committee at the Federal Ministry of Health on the third of November 2019 and permission from the Khartoum Ministry of Health was obtained also. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant separately. Consent was documented as a tick on each questionnaire together with signature.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.