INTRODUCTION

The highest morbidity and mortality due to chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and obesity) are strongly associated with a number of health behaviors.1 Modifiable lifestyle behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise, tobacco use) explain the majority of chronic diseases and account for 60% of all deaths across all demographics and geographic regions.2 Health-promoting behaviors that characterize a healthy lifestyle can reduce both the emotional and the economic burden of chronic diseases.3 If successful, the widespread adoption of a multiple behavior healthy lifestyle is estimated to save over $16 billion in annual medical costs.4

Prospective studies reveal that healthy lifestyle behaviors such as regular physical activity, cancer screening, non-smoking/cessation, low alcohol intake, a healthy diet, and normal body mass index (BMI) increase longevity.5,6,7 Moreover, adopting 3 health promoting behaviors is estimated to reduce chronic disease by over 70%.6 Higher quality of life is also positively impacted by lifestyle, with those adopting four healthy behaviors being 7 times more likely to rate their health as excellent than people reporting no healthy behaviors.8

Health behaviors are inter-related in terms of the psychological, social, and environmental factors that reinforce them, and multiple unhealthy behaviors often coexist. Indeed, statistics reveal that American adults do not meet the minimum guidelines for many health behaviors. For example, more than 33% of American adults do not meet the recommendations for physical activity,9 only 24% of adults consume the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables, over 66% of adults are either overweight or obese, about 35% of adults get insufficient amounts of sleep, and only 31% of adults use lotion that has an SPF of 15 or higher.10 Interventions targeting multiple behaviors simultaneously offer the most promise for sustained behavior change.11

Multiple health behavior change (MHBC) interventions are a relatively new method of initiating lifestyle change that can advance health promotion, increase health benefits and quality of life, and reduce healthcare costs.12,13 The results and conclusions that are drawn from this research are more applicable to everyday life because most people demonstrate multiple health behaviors, or multiple health-risk behaviors. Thus, it is reasonable to create an intervention that targets multiple aspects. Indeed, a person cannot alter one behavior without affecting another one, whether it is intentional or not, thus it is logical to focus on intentionally changing multiple factors at once.

MHBC, which typically focus on special populations, reveals that targeting multiple behaviors may result in more effective health behavior change.14,15 Typically, MHBC interventions target changing two health behaviors, with a focus on diet and exercise, despite the fact that the presence of multiple risk behaviors has an additive or synergistic negative influence on health. For example, having both a poor diet and being physically inactive greatly increases the likelihood of obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.16

Thus, the purpose of our study was to conduct a MHBC intervention focusing on improving the following four health behaviors in adult women: Exercise, diet, skincare, and sleep. The goal of this MHBC intervention is to optimize autophagy. The term autophagy means self-eating, and refers to the processes by which your body cleans out various debris, including toxins, and recycles damaged cell components. We hypothesized that changing these four health behaviors would have significant improvements on women’s body composition, body satisfaction, skin satisfaction, sleep quality, health-related quality of life, and skin health (i.e., wrinkles).

METHODS

Procedures

Prior to study participation, the women completed the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved informed consent and the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q) which is a self-screening tool to determine readiness to start an exercise program.17 Eligible women were then provided with a detailed description of the 60 day MHBC intervention. The following assessments were take on day 0, day 30 and day 60: Subjective self-report questionnaires (i.e., Body Area Satisfaction Scale (BASS), Skin Satisfaction Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)), and objective assessments of body composition (i.e., BOD POD), facial photos taken by a photographer, and vital signs (i.e., blood pressure and heart rate). Each assessment took about 30-45 min to complete. Thirty five women were enrolled in the intervention. One woman dropped out of the study after the 30 day assessments due to a health concern unrelated to study participation. This represented an adherence rate of 97%.

Measures

Subjective assessments

Body area satisfaction scale: This eight-item scale asks participants to indicate their degree of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with discrete body features such as the face, hair, mid torso, upper torso, muscle tone, height, and weight on a Likert scale anchored at the extremes with 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).18 The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale has good psychometric properties and in this study the internal consistency was excellent across the 3 assessments (day 0 α=.92, day 30 α=.88, day 60 α=.93).

Skin satisfaction scale: This ten-item scale assesses satisfaction with the following 10 facial skin areas: Firmness, complexion, glow, pores, youthful appearance, fine lines, elasticity, wrinkles, smoothness, crow’s feet, tone, and overall skin satisfaction on a Likert scale anchored at the extremes with 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).19 This scale has good psychometric properties and the reliability in this study was good (day 0 α=.82, Day 30 α=.86, day 60 α=.85).

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL): HRQOL was assessed with the 4-item Centers for Disease Control (CDC) health days module. Participants rated their perceived overall general health by indicating if their general health was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. Other items on this questionnaire required the participants to indicate the number of days within a month that they felt a certain way. For example: “Now thinking about your PHYSICAL HEALTH, which includes physical illness and injury, how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health NOT good?”. This scale has good psychometric properties.20

Sleep quality: Sleep quality was assessed with the following single item from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: How would you rate your sleep quality overall. Participants used the following Likert type scale to indicate their sleep quality: 1=very good, 2=fairly good, 3=fairly bad, 4=very bad.21 This scale has good psychometric properties.22

Objective assessments

Body composition: Body composition was assessed using the BOD POD which uses air-displacement plethysmography to estimate participant’s fat-free mass, fat-mass, percent body fat, and body mass. The BOD POD assesses weight or body mass by assessing both fat-free mass and fat mass. Fat-free mass includes internal organs, bone, muscle, water, and connective tissue. In comparison, fat mass is the portion of the body that is composed of fat. Participants were measured while wearing tight-fitting clothing (e.g., Lycra swimsuit or compression clothing) according to standardized procedures, and manufacturer’s guidelines were followed for the BOD POD assessment.23

Vital signs: Blood pressure and heart rate were electronically assessed.

Wrinkle severity: Wrinkle severity was assessed by a board certified dermatologist using a 6-point ordinal photonumeric scale on the facial photos that were taken by a professional photographer at day 0, day 30, and day 60. Severity was graded on a 0 (low wrinkles) to 5 (high wrinkles) scale.24

Intervention

Typically, MHBC interventions focus on changing diet and exercise, despite the fact that the presence of multiple risk behaviors has a negative influence on people’s health.25 Thus, the purpose of this intervention was to conduct a MHBC intervention focusing on synergistically improving the following four health behaviors in women: exercise, diet, skincare, and sleep.

The intervention for each health behavior was developed with a goal of activating autophagy.25,26 The exercise consisted of four 30 minute sessions per week with a personal trainer. These sessions included high intensity interval and resistance training. The diet consisted of intermittent fasting in which the participants fasted for 16 hours and then return to their regular diet for 8 hours, all the while focusing on protein cycling. This pattern was followed for 3 days out of the week. For sleep behavior the participants were provided with healthy sleep hygiene education. Finally, for skincare the women followed an autophagy activating skincare regimen twice a day (morning and night) that consisted of a cleanser, brightening serum, an essence spray, a booster, a day cream, and a night cream.

RESULTS

Participants

Participants were a convenient sample of 34 women (M age=44.12, SD=5.93). Most of the participants were Caucasian (n=25), followed by African American (n=5), Hispanic (n=2), Asian (n=1), and other (n=1). The majority of participants had a household income of $120,000 and over (n=18), followed by $80,000-$120,000 (n=7), $50,000-$80,000 (n=7), and less than $50,000 (n=2).The participant’s average BMI was in the overweight range prior to starting the intervention (M=28.25, SD=7.08).

Subjective Assessments

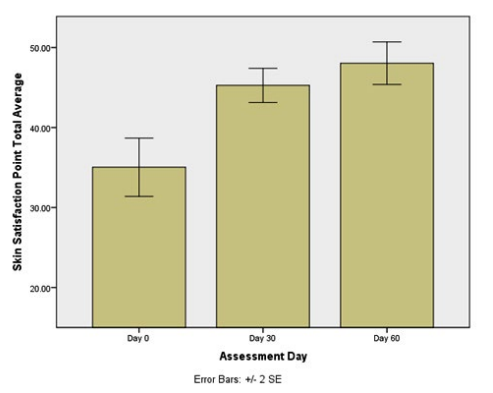

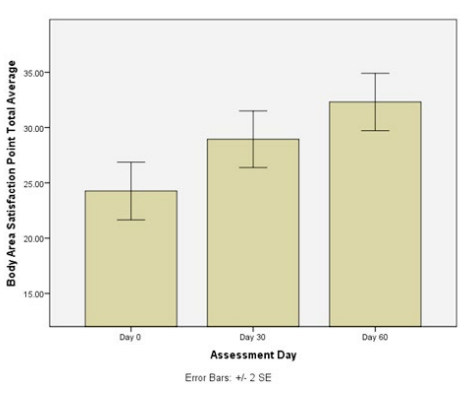

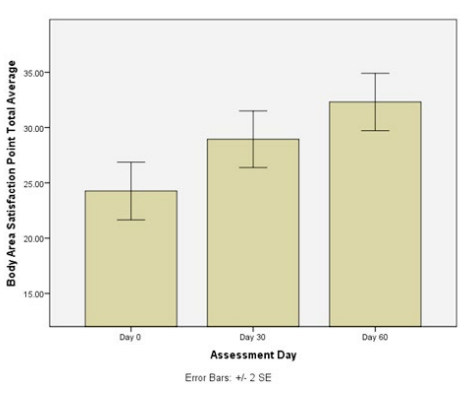

We found a significant improvement in the participants, skin satisfaction scale scores from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (F=20.29, p<.001; See Figure1). We also found a significant improvement in the women’s body areas satisfaction scale scores from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (F=23.03, p<.001; See Figure 2). As well, sleep quality had a significant improvement from day 0 to day 60 (F=5.90, p<.007; See Table 1).

Figure 1: Significant improvement in skin satisfaction scale scores from day 0 to day 30 to

day 60 (F=20.29, p<.001).

Figure 2: Significant improvement in body area satisfaction scale scores from day 0 to

day 30 to day 60 (F=23.03, p<.001)

We found a significant improvement in the women’s overall HRQOL from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (F=5.27, p<.012), with the average rating of HRQOL being “good” for the day 0 assessment and improving to “very good” by the day 60 assessment. A significant improvement was also evidenced in the women’s mental health over the course of the intervention (F=3.63, p>.04). We also found a non-significant improvement in the women’s physical health (F=0.35, p=.71) and the number of days that poor physical or mental health interfered with usual activities (e.g., self-care, work, or recreation (F=2.79, p=.07; see Table 2).

| Table 2: Health-related quality of life scores from day 0 to day 30 to day 60. |

|

Item

|

Day 0

M (SD) |

Day 30

M (SD) |

Day 60

M (SD)

|

| Now thinking about your PHYSICAL HEALTH, which includes physical illness and injury, how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health NOT good? |

4.94 (8.05)

|

4.83 (6.57) |

4.06 (6.30)

|

| *Now thinking about your MENTAL HEALTH, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health NOT good? |

7.6 (7.89)

|

5.96 (8.72) |

4.78 (6.42)

|

| During the past 30 days, how many days did POOR PHYSICAL OR MENTAL HEALTH keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation? |

2.60 (4.31)

|

3.33 (6.16) |

1.91 (4.11)

|

| *Significant differences between day 0, day 30, and day 60 |

Objective Assessments

With regard to skin health, the women had a significant reduction in facial wrinkles from day 0, to day 30, to day 60 (F=57.72, p<.001).

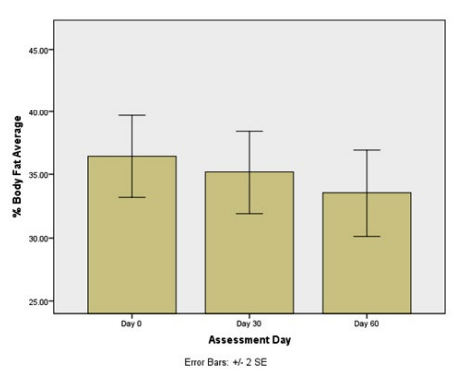

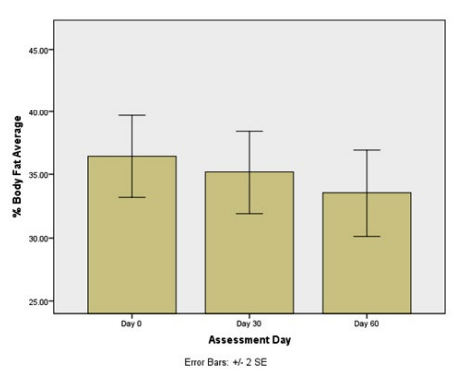

Regarding body composition, we found a significant decrease in body mass (total lbs) of 7.41 lbs from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (F=4.97, p=.01, see Table 1). We found a significant decrease in fat mass of 9.11 lbs from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (F=16.69, p<.001). Regarding fat-free mass, the women had a significant increase of 1.70 lbs from day 0 to day 60 (F=8.91, p<.001). Finally, a significant decrease of 3.65% was evidenced in the women’s % body fat from day 0 to day 30 to day 60 (See Figure 3; F=23.48, p<.001).

Figure 3: Significant improvement in % body fat % on from day 0, to day 30, and to day 60 (F=23.48, p<.001).

| Table 1: Descriptive statistics for the study outcomes. |

|

Item

|

Day 0 |

Day 30 |

Day 60 |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD)

|

|

Sleep Quality**

|

2.11 (0.81) |

2.13 (0.86) |

1.88 (0.65) |

| Facial Wrinkles* |

4.05 (0.54) |

3.60 (0.59) |

3.17 (0.57)

|

|

Skin Satisfaction Scale*

|

35.32 (8.93) |

45.27 (5.46) |

47.31 (6.92) |

| Body Area Satisfaction Scale* |

24.47 (5.62) |

28.56 (5.86) |

31.43 (5.68)

|

|

Body Fat %*

|

36.85 (8.80) |

35.81 (8.60) |

33.20 (8.98) |

| Fat Free Mass (lbs) ** |

104.30 (16.45) |

104.98 (16.44) |

106.00 (16.33)

|

|

Fat Mass (lbs)*

|

66.74 (32.84) |

61.50 (31.44) |

57.63 (31.08) |

| Mass (lbs)* |

171.04 (44.28) |

166.48 (42.51) |

163.63 (43.02)

|

|

BMI*

|

28.25 (7.08) |

27.91 (6.91) |

27.65 (6.81) |

| Systolic BP** |

127.31 (20.71) |

123.19 (18.73) |

122.00 (19.01)

|

|

Diastolic BP

|

83.81 (12.68) |

83.00 (13.06) |

83.42 (14.61) |

| Heart rate** |

74.27 (16.89) |

73.62 (12.56) |

70.23 (12.40)

|

| Notes: BP=Blood pressure; BMI=Body mass index; lbs=Pounds

*Significant differences between day 0, day 30, and day 60

**Significant differences between day 0 and day 60 |

The women’s resting heart rate improved significantly from day 0 to day 60 (F=3.70, p=0.04). We found a significant improvement in systolic blood pressure from day 0 to day 60 (F=2.41, p<0.01. There was no significant time change for diastolic blood pressure over the duration of the intervention (F=0.19, p=0.82).

DISCUSSION

We found that this MHBC intervention, whose underlying development focuses on activating the processes of autophagy at a cellular level, significantly improved women’s body composition and health outcomes. Study findings, study limitations, and future research directions are discussed below. First, we found that the women had significant improvements in their wrinkles as assessed by a board certified dermatologist. In other words, the depth and length of the women’s fine lines and wrinkles decreased over the course of this intervention. Not surprisingly, the women also self-reported an improvement in their skin satisfaction. In short, daily use of the autophagy activating topical skincare products resulted in continual improvements in the women’s skin health (i.e., fine lines and wrinkles) after 30 and 60 days of use.

Second, using the BOD POD as an objective assessment, we found that the women’s body composition improved significantly over the duration of the intervention. Over the course of the intervention, the participants lost an average of almost 7½ lbs of weight. More specifically, however, the women gained over 1½ lbs of fat-free mass(portion of the body that consists of internal organs, bone, muscle, water, and connective tissue) and lost an average of over 9 lbs of fat mass (portion of the body that is composed of fat) over the course of the intervention. The increase in fat-free mass is most likely attributed to the HIIT and resistance training that the women engaged in over the course of the intervention.

With regard to % body fat, the women’s average % body fat was in an excess fat range at the beginning of the study (excess fat range=30.1% to 40%). By day 60 of the intervention the women had lost an average of 3.65% body fat and their body fat rating was approaching a healthier range. Not surprisingly, the women also had a significant improvement in their body satisfaction over the course of the intervention.

Third, the women’s resting heart rate decreased significantly by an average of 4.01 beats a minute by the end of the intervention. A normal resting heart rate for adults’ ranges from 60 to 100 beats a minute. Generally, a lower heart rate at rest implies more efficient heart function and better cardiovascular fitness. Our participants at day 0 had slightly high blood pressure. By day 60 they had an improvement in their systolic, but not diastolic, blood pressure. Of practical importance, at the end of the intervention their blood pressure was approaching the “ideal and healthy blood pressure” range.

In general, our study findings further illustrate that health behaviors are not independent but rather interrelated. Thus, targeting multiple modifiable health behaviors may be most effective for behavior change. In fact, targeting two health behaviors in an individual reduces medical costs by about $2,000 per year.25 Consequently, targeting change in multiple health behaviors has the potential for greater health benefits, enhanced disease prevention, and reduced healthcare costs.

Strengths of our study include examining 4 health behaviors simultaneously. Typically, MHBC interventions focus on only 2 behaviors, usually diet and exercise. To our knowledge, this is the first MHBC intervention to focus on 4 health behaviors. Another strength is that the intervention for each health behavior was implemented with a goal of activating autophagy.26,27 Likely due to their interdisciplinary nature, behavioral health scientists and practitioners are motivated to incorporate MHBC research concepts into their programs.12 Among the MHBC interventions that have been conducted, this is the first lifestyle intervention that focused on altering four different health behaviors (i.e., exercise, diet, sleep, and skincare). Most other MHBC interventions only focus on two health behaviors, usually being physical activity and diet.13

Study limitations of our pilot research include a convenient nonrandomized small sample of motivated overweight women which reduces the generalizability of our findings. Randomized controlled trials, in a variety of populations (e.g., men, obese, older adults), with long-term follow-up are needed to further examine the efficacy of our study findings.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this MHBC intervention was efficacious for improving both objective and subjective health outcomes in the women. It had significant improvements on the women’s overall body composition, body mass, % body fat, skin health, sleep quality, body satisfaction, and skin satisfaction. And although when compared to a single health behavior change intervention it requires more participant adherence and outcome measures 96% of health behavior experts indicate that MHBC interventions are “very-to-extremely important,”.13 Randomized controlled trials, in a variety of populations, with long-term follow-up are needed to further examine the efficacy of our study findings.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Hausenblas H serves as a consultant for W products, who in part funded the study, but she does not receive royalties.