INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a major health problem in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA),1 and has been the most common cancer in women for the past 12 years in KSA.2 Late stage at presentation and occurrence in young women are serious problems, especially in countries like KSA where the development of breast cancer is increasing and developing at a younger age.3,4

Depression is common in patients with cancer, with a recent meta-analysis of 94 studies finding significant symptoms in 29.0% (95% confidence intervals 10.1-52.9) of patients depending on the particular cancer, the particular way that depression is measured, and the particular study and location.5 In one of the first studies to examine depression in those with cancer, now considered a classic, researchers examined 215 women from three outpatient cancer centers in the US finding that adjustment disorder or major depression was present in 50% of patients.6 Similar results have been reported among cancer patients in more recent studies, especially those who are hospitalized.7,8,9

Rates depend largely on the type of measure used to assess depression. A 20-year review of depression after the diagnosis of breast cancer found that rates based on screening measures ranged from 15 to 30%, whereas for depressive disorder based on structured psychiatric interview, they ranged from 5-15%.10 In one of the largest studies, completed since that 20-year review, researchers examined the prevalence of emotional symptoms in 1,996 breast cancer cases seen at Johns Hopkins Oncology Center (Baltimore, Maryland, USA) between 1984 and 2000.11 In that study, only 2.8% had pure depressive symptoms while an additional 10.8% had mixed symptoms of depression and anxiety. Depression is not a benign disease in women with breast cancer, and may adversely affect the course of cancer over time reducing survival.12,13 It may do so by adverse effects on immune function14 and by decreasing the likelihood of accepting and complying with chemotherapy,15 especially hormonal therapy in younger women.16

The highest rates of depression have been reported during the first year after diagnosis,17 especially in women who are younger.18 Women who receive adjuvant chemotherapy report more depressive symptoms,19 which are thought to be due to the distressing side effects that chemotherapy can have (direct effects of chemotherapy on mood, energy level, cognitive functioning, and pain, which all interfere with activity).20 Chemotherapeutic agents such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors can induce sudden and intense menopausal symptoms in breast cancer patients, in whom estrogen replacement therapy is contraindicated.20 Because of this, women with breast cancer may be even more vulnerable to depression than patients with other kinds of cancer.

Cancer stage has generally not been found to be a strong predictor of depression in breast cancer patients,21 although there are numerous exceptions,22,23 and the risk of depression increases with disease severity, level of patient disability, and physical impairment.24 Other factors that increase risk of depression include a past history of psychiatric illness,25 neurotic personality traits,26 and ethnic/emigrant status.27

Another factor related to depression in women with breast cancer is lack of a confiding relationship, and the most confiding relationship in this regard is often the spouse.28 The quality of the marital relationship, however, may suffer following diagnosis and this may further increase depression risk. In fact, a vicious cycle can develop with depression and treatments for depression adversely affect sexual functioning and other aspects of intimacy in marriage.29 Having the care and support of a loving spouse can help to buffer the shocking news of this deadly illness, the side effects of treatment, the life-threatening complications of the disease, and the constant fear of recurrence among those women who achieve remission. However, the diagnosis of cancer can also adversely impact the emotional state of spouses, many of whom experience significant depressive symptoms as well, making them less able to provide support and care during this time.30,31 Lack of spousal support, then, is not uncommon. Depression can also adversely affect the woman’s ability to fulfil her obligations at home, particularly for young women who are still raising children.16 All of these factors can have a devastating effect on the marital relationship.

SAUDI ARABIA

Little systematic information exists on the mental health of women living with breast cancer in the Middle East and we could find no research from Arabic countries that examined how the quality of the marital relationship may influence the likelihood of these women developing depressive symptoms. An even greater research gap exists in Saudi Arabia, where there is almost a total absence of data on depression and other emotional symptoms experienced by married women with breast cancer. This conservative country has a rich historical past rooted in the culture and traditions of Bedouin tribes and is the place where the great religion of Islam was born and now Muslims from all over the world come to worship. We were able to locate only one study of the mental health of cancer patients, which was conducted at the King Khalid National Reserve Hospital and involved 30 cancer patients on the inpatient service (including 9 patients with breast cancer).32 Half of the patients (n=15) had a mental disorder based on (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition) DSM-IV clinical criteria, including nine with adjustment disorder, three with major depression, and three with generalized anxiety disorder; no information on correlates or specific information on breast cancer was provided.

The only study that has examined the knowledge and attitudes of men toward breast cancer in Saudi Arabia (and the only study examining any psychological or social aspect of breast cancer in this country) examined 500 men who accompanied their female relatives to outpatient clinics at King Abdulaziz University hospital in Jeddah.33 Nearly a quarter (24%) did not know the symptoms of breast cancer, and 13% thought that all cases of breast cancer ended with mastectomy. When the participants were asked what they would do if their wives were diagnosed with breast cancer, 9.4% said they would leave their wives.

Given the gap of knowledge on depression in women with breast cancer in Saudi Arabia, a preliminary study to examine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and to identify risk factors for depression (quality of the marital relationship, in particular) among women with breast cancer living in a large urban city in this country was conducted. Relationship with anxiety symptoms have been reported elsewhere.34

OBJECTIVES

The present study sought to (1) determine the preva lence of depressive symptoms in younger and middle-aged married women with breast cancer being seen in a university-based outpatient clinic in Saudi Arabia; (2) determine whether marital relationship quality was associated with depressive symptoms, independent of other risk factors; and (3) determine whether nationality (Saudi vs. emigrant) interacted with the relationship between marital quality and depression. It was hypothesized that depressive symptoms will be prevalent, that higher marital quality will be strongly and inversely related to depressive symptoms, and that the inverse relationship between marital quality and depressive symptoms will be strongest among Saudi citizens who are likely most influenced by the surrounding Arabic and Bedouin culture.

METHODS

In this descriptive study, a consecutive series of women diagnosed with breast cancer attending the outpatient clinic at the Sheikh Mohammed Hussein Al-Amoudi Breast Cancer Center of Excellence at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) in Jeddah were approached. Inclusion criteria were (1) age 18-65; (2) documented diagnosis of breast cancer; (3) female; (4) currently married; and (5) attending the clinic on days that interviewers were present.

The questionnaire was translated into Arabic. The study was explained to participants and informed consent was obtained. Medical students, trained by KAU psychiatry faculty, administered the questionnaire to eligible participants. The women filled out the questionnaires by themselves without assistance. The ethics committee of King Abdulaziz University Hospital approved the study.

Questionnaire

Demographic characteristics assessed included age, nationality/citizenship (Saudi=1 vs. emigrant=0), education level (none=1, primary school only=2, high school only=3, university=4, post-graduate=5), employment status (yes=1 vs. no=0), and family yearly income (<36,000 SAR=1; 36,000 to 60,000=2;>60,000=3).

Cancer-related:

Duration of illness in months and type of treatment received (radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or surgery) were assessed.

Depression:

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)35,36 is a self-rated scale measuring anxiety and depressive symptoms in outpatient medical populations, and has been used in many studies of women with breast cancer,37,38 including at least two studies in the Middle East.39,40 The HADS includes a 7-item depression subscale Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression (HADS-D) where each item is rated from 0 to 3, with scores ranging from 0 to 21 (higher scores indicating greater depression). Scores 0-7 indicate no significant depression, 8-10 “possible” depression, and >10 “probable” depression. These cut-offs have been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 80% when compared against clinical interviews.41 The Cronbach’s alpha for the depression subscale has been reported to be high (0.86).42 In the present sample, the alpha was 0.84, which is above the threshold of 0.70 as recommended.43

Marital relations:

Marital relationships were assessed with two standard scales: the 6-item subscale of the Spousal Perception Scale (SPS)44 and the 6-item Quality of Marriage Index (QMI).45 The SPS is a self-rated scale that includes two 6-item subscales, one assessing spousal emotional support and one measuring emotional strain. We use here the 6-item perceived emotional support from spouse subscale. Each of the 6 items is rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot), with a score range from 6 to 24 where higher scores indicate greater spousal support. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale is reported to be 0.91.46 In the present study, the internal reliability was likewise high (alpha=0.85). The QMI is a self-rated scale that includes items assessing the “essential goodness of a relationship.” Each of the 6 items is rated on a scale from 1 (very strong disagreement) to 7 (very strong agreement) with a theoretical scale score ranges from 0 to 42 (higher scores indicating a more positive marital relationship). Internal reliability of the QMI is reported to range from 0.91 to 0.97 in husbands and wives.45 The alpha in the present sample was 0.89. In order to assess overall marital quality and limit the number of analyses, the SPS and QMI were combined to form a single 12-item scale whose score ranged from 6 to 66 (alpha=0.91 in the present sample).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic, cancer-related, psychological, and marital adjustment characteristics (Table 1). Bivariate correlations (Pearson r) were used to construct a correlation matrix with all study variables (Table 2). For multivariate analyses, income was dichotomized into low (<36,000 SAR/year=0) vs. high (>36,000=1), and education was dichotomized into low (0=no education or grammar school [primary] only) vs. high (1=high school [secondary] or greater). Blocks of variables were entered in a stepwise fashion into three general linear models predicting anxiety symptoms: Model 1 included only sample demographics; Model 2 added cancer-related factors; and Model 3 added overall marital quality (Table 3). Since the sample size was relatively small, only variables significant at p<0.10 were carried forward into later models. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses, significance level was set at p<0.05 and trend level was set at 0.05<p<0.10. Analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The SAS statistical package (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used to perform analyses.

Table 1: Characteristics of the sample.

emographics Mean (SD) (range) %(n)

Age, years 48.9(7.1)(35-65)

Nationality, % Saudi (n) 58.3(28)

Education, % high school or more (n) 73.5(36)

Employment status, % employed (n) 31.9(15)

Family income per month (SAR), % (n)

<3000 (750 USD) 12.2(6)

3000-5000 (750-1250 USD) 61.2(30)

>5000 (1250 USD) 26.5(13)

Cancer characteristics

Duration of illness, months 38.4(48.9)(0.5-180)

Treatment, % (n)

Radiation therapy 57.1(28)

Chemotherapy 83.7(41)

Surgery 89.8(44)

Depression

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-D (total) 6.2(4.3)(0-17)

(1) Enjoys thing as much as used to (reverse) 1.0 (0.9) (0-3)

(2) Can laugh & see funny side (reverse) 0.9(0.8)(0-3)

(3) Feels cheerful (reverse) 0.9(0.8)(0-3)

(4) Feels slowed down 1.0(0.8)(0-3)

(5) Have lost interest in appearance 1.1(1.0)(0-3)

(6) Looks forward with enjoyment (reverse) 0.6(0.8)(0-3)

(7) Enjoys TV, radio program, book (reverse) 0.7(0.9)(0-3)

HADS-D score 0-7 (no significant depression) 70.8(34)

HADS-D score 8-10 (possible depression) 8.3(4)

HADS-D score 11-17 (probable depression) 20.8(10)

Marital Quality

Spousal Perception Scale (SPS) (total) 16.7(3.9)(6-23)

(1) Spouse or partner really cares 2.7(0.8)(1-4)

(2) Spouse understands the way you feel 2.6(0.8)(1-4)

(3) Spouse appreciates you 2.9(0.8)(1-4)

(4) Can rely on spouse if have serious problem 2.8(0.9)(1-4)

(5) Can talk about worries with spouse 2.8(0.9)(1-4)

(6) Can relax and be yourself around spouse 2.8(0.9)(1-4)

Quality of Marriage Index (QMI) (total) 31.0(5.7)(9-40)

(1) Has good relationship with partner 5.2(1.0)(2-7)

(2) Relationship with partner is stable 5.1(1.1)(2-7)

(3) Has strong relationship with partner 5.0(1.2)(1-7)

(4) Relationship with partner makes me happy 5.3(1.1)(2-7)

(5) Fells like part of a team with partner 5.2(1.3)(1-7)

(6) Could not be more happy in relationship 5.2(1.5)(1-7)

Total Marital Quality (SPS+QMI) 47.6(8.7)(15-62)

n=47-49

Table 2: Bivariate correlations between all variables.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

- Age .12 -.13 -.02 .16 .27* .30* .10 .17 -.23 -.16 -.10 -.15

- Nationality – .36* .42* .48* .16 .19 -.04 .13 -.28* -.13 -.09 -.13

- Education – – .63* .66* .22 .18 -.04 -.08 -.48* .27* .30* .31*

- Employment – – – .31* .06 .13 -.05 .09 -.33* .29* .15 .26*

- Income – – – – .38* .27* -.08 -.03 -.31* .00 .09 .04

- Duration – – – – – .59* .33* .22 -.19 .11 .19 .16

- Radiation therapy – – – – – – .51* .25* -.38* -.05 -.01 -.04

- Chemotherapy – – – – – – – -.15 -.21 .01 -.05 -.01

- Surgery – – – – – – – – -.05 -.21 -.09 -.18

- HADS-D – – – – – – – – – -.19 -.20 -.21

- QMI – – – – – – – – – – .65* .94*

- SPS – – – – – – – – – – – .87*

- MQ-total – – – – – – – – – – – –

SPS: Spousal Perception Scale; QMI: Quality of Marriage Index; MQ-total: SPS + QMI; HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression, *p<0.10

Table 3: Multivariate model examining relationships between depression (HADS-D) and overall marital quality (MQ-total).

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Demographics B(SE) B(SE) B(SE)

Age -0.15(0.05)*** -0.12(0.06)** -0.12(0.05)**

Nationality 0.64(1.17) — —

Education -3.73(1.65)** -4.63(1.23)**** -4.33(1.21)****

Employment -1.48(1.23) — —

Income -2.76(1.96) — —

Illness characteristics

Duration of illness — 0.01(0.01) —

Rx (radiation vs. other) — -2.37(1.35)* -1.96(1.11)*

Marital quality

MQ-total — — -0.09(0.06)

Model R-square (n) 0.44(46)**** 0.37(48)**** 0.40(48)****

Rx: treatment; SPS: Spousal Perception Scale; QMI: Quality of Marriage Index; MQ-total: SPS + QMI

HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression

*0.05<p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01, ****p<0.001

RESULTS

All women (100%) approached by the medical students agreed to participate (n=50), although one participant completed only part of the questionnaire, leaving a final sample of 49. Women were on average 48.9 years old; slightly more than half the sample was Saudi citizens (58%); about three-quarters (74%) had a high school education or more; about one-third (32%) was employed; and the majority (61%) had a family income of 36,000-60,000 SAR/year ($9,720 USD-$16,200 USD) (Table 1). Average time since breast cancer diagnosis was about 3 years (38.4 months), although duration ranged from 2 weeks to 15 years. Most women had undergone breast cancer surgery (90%) and chemotherapy (84%), and the majority had received radiation therapy (57%). Overall marital adjustment was moderate with a score of 47.6 on a scale whose possible range was 6-66.

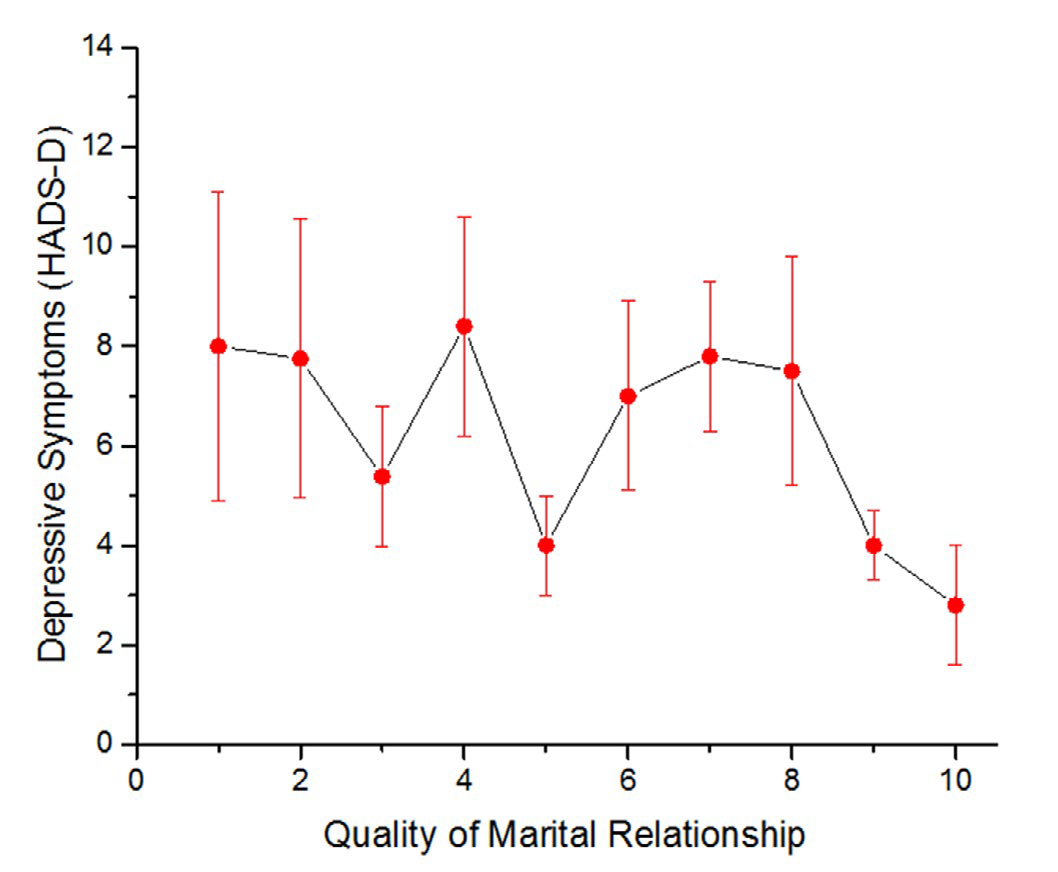

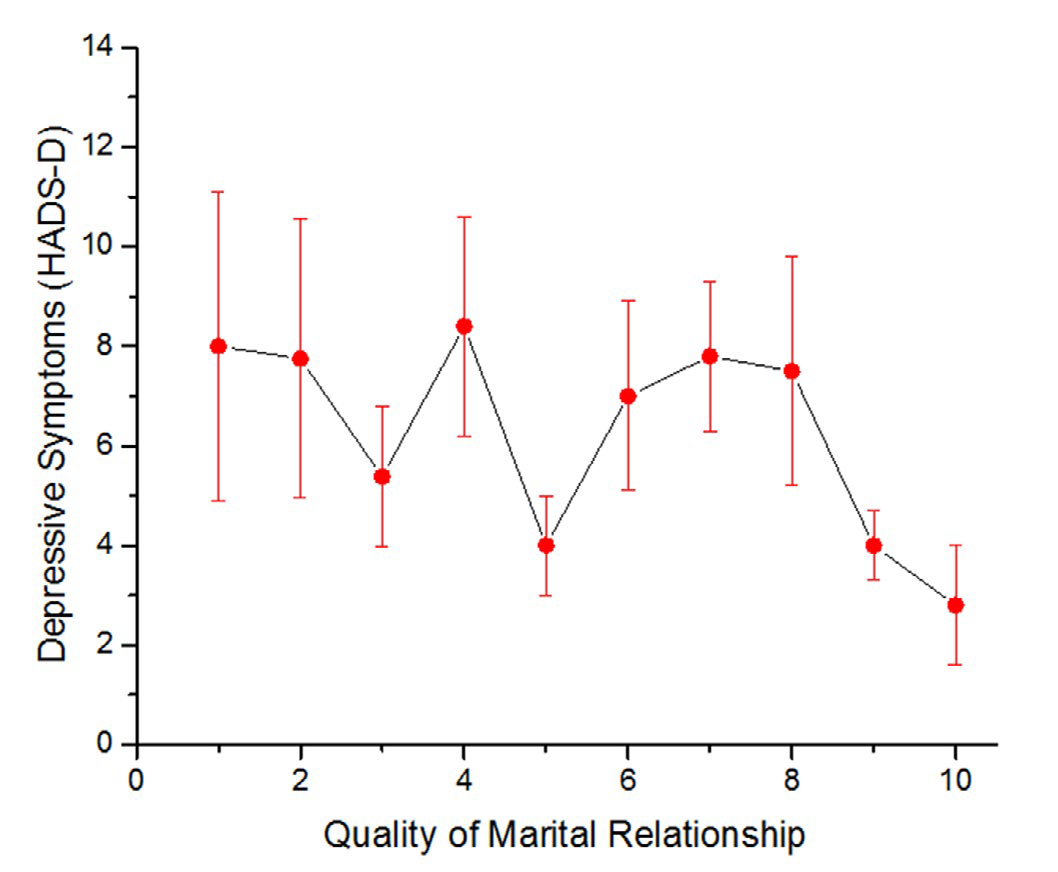

The average number of depressive symptoms in women was 6.2(SD=4.3). The prevalence of ‘possible’ significant depression (HADS-D score 8-10) was 8.3% and ‘probable’ depression (HADS-D score 11-21) was 20.8%. The most common depressive symptom was loss of interest in appearance. Bivariate correlates of depressive symptoms were emigrant status (vs.Saudi nationals) (r=-0.28, p=0.06), lower education (r=-0.48, p=0.0006), lack of employment (r=-0.33, p=0.02), lower family income (r=-0.31, p= 0.03), and not having received radiation therapy (r=-0.38, p=0.007) (Table 2). Time since diagnosis was not related to depressive symptoms. There was a weak, nonsignificant inverse relationship between depressive symptoms and perception that spouse cares and really understands (SPS) (r=-.20, p=0.17), score on the marital quality index (MQI) (r=- 0.19, p=0.20), and marital relationship quality overall (r=-0.21, p=0.15) (see Figure 1, where marital quality divided into deciles (tenths) is plotted against depressive symptoms).

Figure 1: Relationship between quality of the marital relationship and depressive symptoms (standard error). HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression.

Multivariate analyses indicated that only age (B=-0.12, SE=0.05, p=0.03) and education (B=-4.33, SE=1.21, p=0.0009) were significantly and independently associated with depressive symptoms (Table 3, Model 3). As in the bivariate analyses, no significant relationship was found between overall marital quality and depressive symptoms, although a trend in the expected direction was present (B=-0.09, SE=0.06, p=0.13).

Nationality did not influence the relationship between marital quality and depression. The estimate from the regression model for the nationality by marital quality interaction was B=0.10 (SE=14.0, t=0.75, p=0.46). In other words, the relationship between overall marital quality and depressive symptoms was not stronger in women who were Saudi citizen (vs. emigrant), as hypothesized.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the prevalence of depressive symptoms and correlates (marital adjustment, in particular) among married women with breast cancer in Saudi Arabia. More than one in five of these women seen in a university-based outpatient clinic had depressive symptoms severe enough to qualify for a probable depressive disorder. However, contrary to the study’s expectations, the quality of the marital relationship was not significantly related to depressive symptoms, and there was no interaction with nationality (Saudi vs. emigrant status).

Several reasons help to explain why this study was unable to identify a significant relationship between marital relationship quality and depressive symptoms in these women. First was the relatively small sample size that reduced the power of the study to detect significant relationships. Trends in the expected direction were identified, but did not reach statistical significance. Perhaps a larger sample size would have reduced the likelihood of such a Type II error. Second, women with breast cancer in the Al-Amoudi Breast Cancer Center at KAU receive excellent care, with special attention paid to the effect of the cancer diagnosis on the marital relationship and the woman’s mental health. This could reduce both the prevalence of depressive symptoms and strength of relationship to marital quality.

A third explanation for lack of a significant relationship between marital quality and depressive symptoms may have involved a selection effect. Women included in this study were on average three years from initial diagnosis of their breast cancer and were still married. Women in whom the breast cancer diagnosis resulted in significant marital discord may have divorced soon after diagnosis, and would not have been included in the present study. Recall that a survey of men accompanying female family members to the clinics at this same university hospital found that nearly 10% said they would leave their lives if they were diagnosed with breast cancer.33 Such a selection effect may have reduced variability in responses and decreased the ability to detect significant effects in these women whose marriages had endured and stabilized.

Finally, longstanding religious and Bedouin cultural traditions may have allowed women to accept and successfully cope with a lack of spousal support. In this strongly patriarchal society, then, women may have adapted to their cancer by seeking support from other family members or from their religious beliefs.47

More important than marital quality in terms of depression risk in this study was level of education, age, and type of treatment for their cancer. Those with a lower level of education and younger age were more likely to experience depressive symptoms, as were women who did not receive radiation therapy. This is one of the first studies (and possibly only study) to report that education level has an association with depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer, although it is consistent with research finding that minorities, emigrants, women with low income, unemployed, or unmarried (i.e., women with breast cancer from disadvantaged groups) experience greater risk of depression.27,48,49 Bivariate analyses in the present study also indicated a weak inverse relationship between nationality and depressive symptoms, suggesting that emigrant (minority) status was associated with increased depression. This association, however, was accounted for by the lower education of emigrant women (vs. Saudi nationals) in multivariate analyses.

As indicated earlier, numerous studies report that younger women with breast cancer have an increased risk of depression,18,27 and an increased risk of negative health consequences from breast cancer due to a reluctance to accept or comply with hormonal therapies that adversely affect marital intimacy.29 We too found that younger age was associated with more depressive symptoms, especially in multivariate analyses that controlled for education. Younger women have more family and work responsibilities. The development of breast cancer and its treatments can adversely affect energy level and the ability to engage in physical (and sometimes cognitive) activities. The fact that breast cancer may not be expected (as in older age) can also make it more difficult for younger women to cope.

Finally, those who did not receive radiation therapy were more likely to experience depressive symptoms than women who did. Radiation therapy may have fewer distressing side-effects than either surgery or chemotherapy, and this may account for this finding. Chemotherapy, in particular, has been associated with many side effects and so might be more likely to interfere with life and lead to depression. Alternatively, the receipt of radiation therapy may indicate that the breast cancer was localized and not as advanced,50 and might have served as a proxy for cancer stage.

LIMITATIONS

A number of limitations affect conclusions that can be drawn from these findings. The sample was relatively small and was acquired from only one university breast cancer clinic in Jeddah, which may limit our ability to generalize results to women with breast cancer in rural areas or those seeking care in non-university settings. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the analyses precludes saying anything about the direction of causation in the relationships detected. Another weakness is our use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression rather than a structured psychiatric interview. We chose HADS because of its widespread use in studies of breast cancer patients and because the shortness of the scale reduced interview burden on these women, many of whom were frail. Finally, not assessed was detailed information on cancer stage, severity of functional impairment, and concurrent medical co-morbidities, factors known to be correlated with depressive symptoms in other studies.24,27

However, the study also has a number of strengths. First, standard measures of depressive symptoms and marital quality with established psychometric properties were used, and the data were carefully analyzed using bivariate and multivariate statistics. Second, this is the first report from Saudi Arabia on the prevalence of depressive symptoms, correlates, and relationship between marital quality and depression in married women with breast cancer. Given the important role that religion, cultural, and social forces play in this Middle Eastern country,51 even these preliminary findings will be of value in future investigations that examine how quality of the marital relationship influences depression in this setting.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Depressive symptoms are common in married women with breast cancer being seen as outpatients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The primary risk factors for depression in this setting are younger age and lower education level. Although weak trends were found in the expected direction, no significant relationship was found between perceptions of spousal support or quality of the marital relationship and depressive symptoms. Low power (given sample size), high quality of care received in this university-based cancer clinic, and a possible selection effect may at least partly explain this lack of association. Nevertheless, given the relatively high prevalence of depressive symptoms in this population, and the potential for cultural influences to affect the marital relationship after breast cancer diagnosis, further research is needed that utilizes a larger sample size, a design that is prospective (beginning immediately after the diagnosis), and controls for severity of illness and functional disability. Clinicians who treat breast cancer patients in Saudi Arabia should also be particularly alert for symptoms of depression in young women and those with lower education.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by Sheikh Mohammed Hussien AlAmoudi Center of Excellence in Breast Cancer, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.