INTRODUCTION

Dendritic cells (DCs) have a central role in body’s immune system by triggering antigen-specific immune responses. DCs are the most potent antigen presenting cells (APCs) as they have a high capacity to take up antigens from the periphery, and processing and presenting them at the cell surface in the context of both major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules. After antigen capture, DCs migrate to the peripheral lymphoid tissues and upregulate expression of MHC molecules as well as costimulatory molecues at the cell surface, and secrete several chemokines and cytokines to attract T cells, as well as other immune cells, and induce their differentiation towards specialized effector immune cells.1,2 DCs are functionally divided into immature DCs and mature DCs. Immature DCs are usually found in nonlymphoid tissues and express pathogen/ pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as toll like receptors (TLRs) to explore periphery from pathogenic agents. Immature DCs have a high capacity to capture and process antigens, but are unable to react with T cells. These cells have intracellular MHC class II molecules and express low levels of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules on the cell surface compared with mature cells. After antigen capture, they migrate to peripheral lymphoid tissues and become mature. Mature DCs express upregulated levels of MHC molecules, costimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD80 (B7-1), and CD86 (B7-2), and adhesion molecules such as lymphocyte-function associated antigen-3 (LFA-3/CD58) and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1/CD54). Expression of MHC molecules and MHC-peptide complexes on DCs is 10-100 fold more than other professional APCs, including B cells and monocytes. Mature DCs can also produce several cytokines and other soluble factors. Phenotypical and functional changes occur within one day after exposure of DCs to maturation stimuli.2,3 Therefore, mature DCs are efficient in activation of naïve T cells as well as some other immune cells. Maturation of DCs is mediated by different stimuli including microbial products such as LPS, and peptidoglycan, TLR agonists, cytokines, prostaglandins, and CD40 ligand (CD40L) expressed on T cells. TNF-α and CD40L can block differentiation of granulocytes from precursor cells and stimulate terminal maturation of DCs.4

Since mid-1990’s, DCs pulsed with peptide antigens were used to induce antigen-specific immune responses. DCs pulsed with peptides or soluble protein induced antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells.5,6 Because tumor specific/associated antigens are not identified in most cancers, tumor cell lysates were extensively used as a source of tumor antigens for antigen loading of DCs. Stimulation of T cells by tumor lysate-pulsed DCs led to generation of tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells.7 Furthermore, total tumor antigen vaccines contain both MHC class I- and class II-restricted epitopes, hence, these vaccines can induce multivalent CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. In general, tumor cell lysate-pulsed DCs have produced better clinical responses than highly specific tumor vaccines. Other approaches, including tumor cell ribonucleic acid (RNA) and fusion of tumor cell to DC, have also been used for antigen loading of DCs.4 Recently, encapsulated peptides in biodegradable nanoparticle have been successfully used to enhance DC presentation of peptides in the context of MHC class I and class II molecules.8 Virally-engineered DCs have also been used to activate antigen-specific immune responses against murine tumors9,10,11 and human cancer cell lines.12

In this work, we produced DCs from bone marrow precursor cells, assessed their immunophenotype and function in vitro as well as their antitumor activities in vivo, and investigate effects of maturation status of DCs and influences of the tumor environment on the antitumor efficacy of DCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor Cell Line and Culture Media

Fibrosarcoma cell line, Wehi-164, was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gipco-Invitrogen, UK) supplemented with 2 mM Lglutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), penicillin-streptomycin mixture with 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gipco-Invitrogen, UK). Cell culture flasks were incubated at 37 °C in atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. Cells were sub-cultured every 3 days after treatment with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, UK).

Antibodies and Reagents

Fluorochrome conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were used to examine DCs immunophenotype by flow cytometry. FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c (N418), PE-conjugated anti-mouse I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD40 (1C10), CD80 (16- 10A1), CD86 (GL-1), purified anti-mouse CD16/32 and appropriate isotype control mAbs conjugated to FITC or PE were purchased from Biolegend (CA, USA). Cytokines used for ex vivo generation and maturation of DCs, included recombinant mouse-granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (rmGM-CSF), rm-interleukin-4 (rm-IL-4), and rm-TNF-α, were obtained from BD-Pharmingen (CA, USA).

Ex Vivo Generation of DCs from Bone Marrow Precursor Cells

Bone marrow cells were obtained from femur and tibia of 6 to 10 wk old BALB/c mice by flushing into RPMI-1640 medium (Gipco-Invitrogen, UK) and red blood cells (RBC) were depleted by RBC lysis buffer (Biolegend, USA). After washing, 0.7-1.5×106 cells/ml were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol (Daejeon, Korea), penicillin-streptomycin mixture with 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (SigmaAldrich, UK), 1000 IU/ml GM-CSF (BD-Pharmingen, USA), 500 IU/ml IL-4 (BD-Pharmingen, USA), and 10% FBS (Gipco-Invitrogen, UK). Cell culture plates were incubated at 37 °C in atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. On days 3 and 5, fresh culture medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 1000 IU/ml GM-CSF, 500 IU/ml IL-4, and 10% FBS were added to the plates. Morphology and immunophenotype of ex vivo generated DCs were analyzed by microscopically examination and immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric analysis, respectively.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Flow Cytometric Analysis of Ex Vivo Generated DCs

Non-adherent cultured cells were harvested on day 6, washed two times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and stained with anti-CD11c, anti-I-A/I-E, anti-CD40, anti-CD80, and antiCD86 FITC- or

PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. After incubation at 4 °C in the dark for 30 minutes, cells were washed by PBS supplemented with 0.5% FBS and immediately assayed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA). Acquired data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, USA). In all experiments, isotypically stained cells were used to set cursors so that the results of ˂1% of cells were considered positive.

Tumor Cell Lysate Preparation

Fibrosarcoma tumor cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS, as mentioned in the previous section. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed in PBS, and resuspended in PBS at 1×107 cells/ml. For preparation of tumor cell lysate, fibrosarcoma cells underwent four cycles of freezing and thawing in liquid nitrogen and 37 °C water bath, respectively. At this point, 100% of cells were seen to take up trypan blue when assessed by light microscopy. After centrifugation at 300 g for 10 minutes, the supernatants were taken and stored at -20 °C or -75 °C.

Tumor Antigen Loading of DCs

On day 6, DCs were harvested and cultured in fresh RPMI-1640 medium at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml. For tumor antigen loading, tumor cell lysate was added to the DCs at a ratio of three tumor cell equivalents to one DC. Coculture continued for four hours. Some DCs did not cocultured with tumor cell lysate (unpulsed DCs).

Induction of Maturation in DCs

Maturation of ex vivo generated DCs was stimulated with TNF-α and/or LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, UK). After antigen loading of DCs, 5 ng/ml TNF-α and 0.5 µg/ml LPS were added to the culture medium of DCs separately or in combination. Culture incubation was continued for another 24 hours. Some DCs cultured in the absence of TNF-α/LPS (immature DCs). Maturation of DCs was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of upregulation of MHC-II molecules and costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 on DC cell surface.

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF DCs IN VITRO

Analysis of Proliferation Induction in Lymphocytes

Antigen loaded mature DCs are potent stimulator of proliferation in lymphocytes. For evaluation of this property in ex vivo generated DCs, DCs (2×104 cells/ml) were cocultured with splenocytes (2×105 cells/ml) obtained from naïve BALB/c mice at a responder-to-stimulator ratio of 10:1 (splenocyte:DC) in RPMI1640 containing 15 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mM nonessential amino acids (Biochrom AG, Germany), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS in 96 well plates. After incubation of plates for 96 hours at 37 °C in atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% humidity, MTT, 3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5- diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide, (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) was added to the wells and proliferation was assessed according to the manufacturer instructions.

Measurement of IL-12 Secretion

DCs can direct differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells toward type 1 helper T (Th1) cells, a major subset of CD4+ T cells with antitumor activity, by secretion of large amount of interleukin-12 (IL-12).13 IL-12 activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) signaling pathway and the transcriptional factor T-bet, which are involved in the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th1 cells. This cytokine also activates natural killer (NK) cells14 and has potent antitumor activities.15

Therefore, we assessed IL-12 secretion by ex vivo generated DCs. DCs were cocultured with splenocytes at a responder-to-stimulator ratio of 10:1 (splenocyte:DC) in RPMI-1640 containing 15 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mM nonessential amino acids (Biochrom AG, Germany), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. After 48 hours, culture supernatants were collected and IL-12 secretion was measured by measuring IL-12p70 in the supernatant of cultures using a commercial ELISA kite (R&D systems, Australia) according to the manufacturer instructions.

EVALUATION OF ANTITUMOR EFFECTS OF DCs IN VIVO

Vaccination with Mature DCs

For evaluation of antitumor effects of ex vivo generated DCs in vivo, DCs (1×106 cells/200 µl) pulsed with tumor antigens, or unpulsed DCs, matured with TNF-α were injected subcutaneously to the flank of female 8-10 wk old BALB/c mice (antigen pulsed DC group and unpulsed DC group, respectively). Two groups of mice were also injected with tumor cell lysate and PBS (tumor lysate group and PBS group, respectively). One other group was considered as healthy control group that did not receive any treatment (number of mice in each group was 3-5). Forty-eight hour later, fibrosarcoma tumor cells (0.7×106 cells/200 µl) were inoculated subcutaneously to the same flank (previously injected site) of all mice, except for healthy control group. Tumor growth was examined every 3-4 day up to 40 days after tumor inoculation. Tumor sizes were measured by a digital caliper and tumor volumes were calculated by the formula “length×width2 ×0.5”.

Injection of Immature DCs Directly into the Tumor Tissue

For evaluation of the effects of the tumor microenvironment on antitumor activity of ex vivo generated DCs, immature DCs were injected to mouse harboring large established tumor. Fibrosarcoma tumor cells (1-1.5×106 cells/200 µl) were inoculated subcutaneously to right flank of mice. After 30 days, immature DCs were injected directly into the tumor tissue in three different sites. Tumor growth was measured every 3-4 day up to day 50. One group of mice received PBS and another group was considered as healthy control group (n=5).

RESULTS

Morphology and Immunophenotype of Ex Vivo Generated DCs

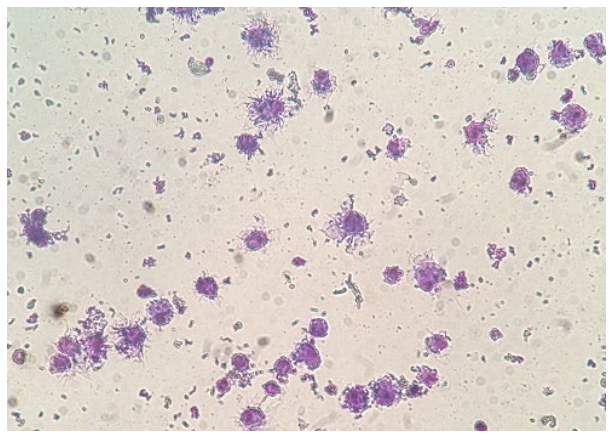

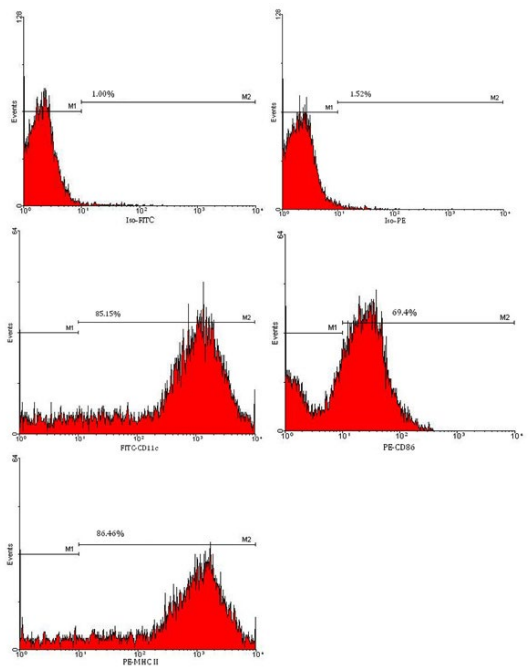

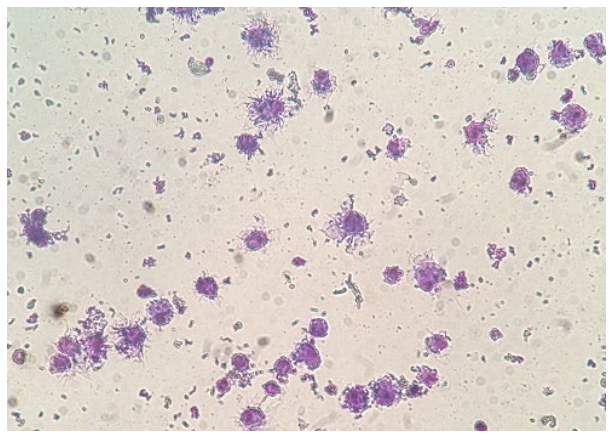

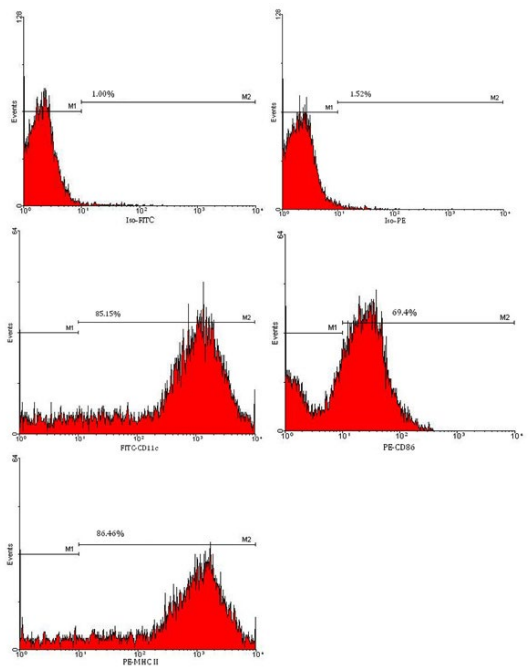

Some bone marrow cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 were differentiated into DCs within two days of culture, but the numbers of DCs showing the DC morphology were increased by enhancing the culture duration time. Cells cultured in the absence of GM-CSF and IL-4 did not show any cellular projections (dendrites) and enlarged cell size. Also, the numbers of cells in these cell culture wells were diminished at the end of incubation period. In contrast, cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 showed large cell sizes and enormous cellular dendrites indicative of DCs (Figure 1). Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface expression of CD11c, MHC class II, CD40, CD80, and CD86 molecules also confirmed the generation of DCs from bone marrow precursor cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. At day 7 of culture, more than 84% of cells expressed CD11c and MHC class II molecules (Figure 2). Expression of costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 was also upregulated at the cell surface of cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. These cells did not express CD4 or CD8 on their cell surface (data did not show). At the end of culture period, 5-7×106 DCs were obtained from 2-2.5×107 cultured bone marrow cells.

Figure 1: Bone marrow cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 showed typical dendritic morphology. Cells were cytocentrifuged for Giemsa staining (×400).

Figure 2: Flow cytometric analysis of ex vivo generated DCs. DCs differentiated from bone marrow precursor cells were examined for the expression of DC cell surface marker CD11c, costimulatory molecules CD86, as well as MHC class II molecules by flow cytometric analysis.

In Vitro Functional Analysis of DCs

Induction of proliferation in splenocytes: Results of MTT assay showed that tumor antigen-loaded DCs matured with TNF-α or LPS plus TNF-α induced proliferation of splenocytes, but immature DCs did not. Splenocytes cultured in the absence of DCs did not proliferate. Cell counting by trypan blue exclusion test and microscopically examination also confirmed proliferation of splenocytes in the presence of mature DCs as numbers of splenocytes were enhanced 3-4 fold after four days. There was no increase in the numbers of splenocytes cultured in the absence of DCs.

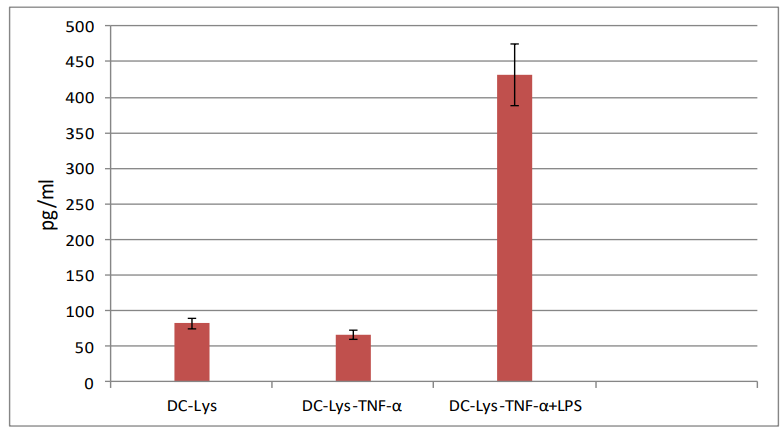

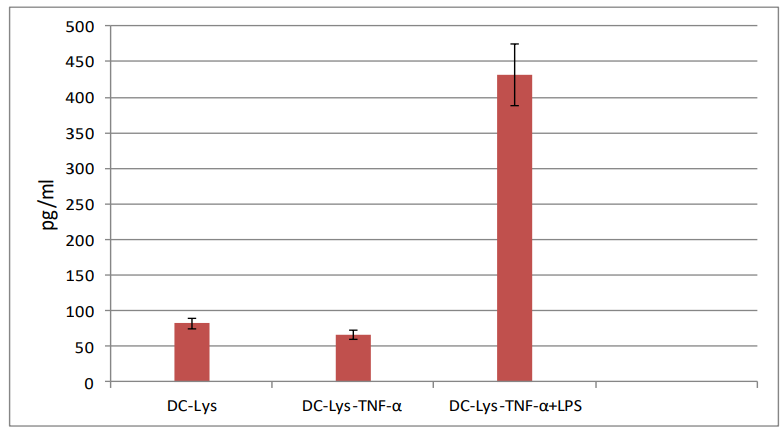

IL-12 secretion: IL-12p70 was not detectable by the commercial standard ELISA kit in the culture supernatant of immature DCs cocultured with splenocytes, as well, in the supernatant of splenocytes cultured alone. IL-12p70 level was low in the supernatant of TNF-α-induced mature DCs cocultured with splenocytes. In contrast, high level of IL-12 was detected in the supernatant of LPS plus TNF-α induced-mature DCs cocultured with splenocytes (Figure 3).

Figure 3: IL-12p70 secretion by ex vivo generated DCs. DC-Lys: DCs pulsed with tumor

cell lysates, DC-Lys/TNF-α: DCs pulsed with tumor cell lysates and then matured in the

presence of TNF-α; DC-Lys/TNF-α+LPS: DCs pulsed with tumor lysates and then matured in the presence of TNF-α and LPS.

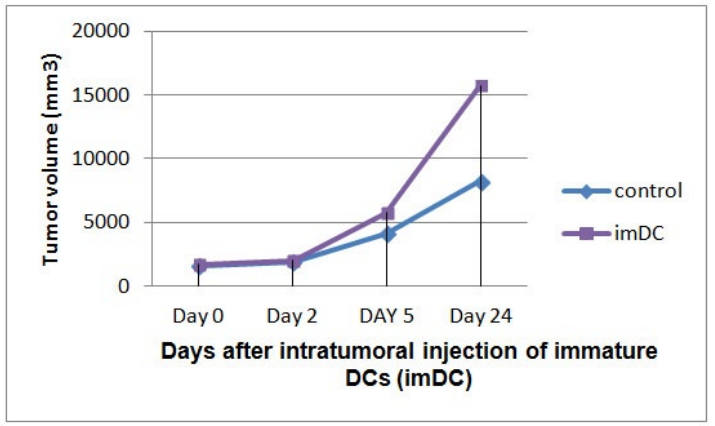

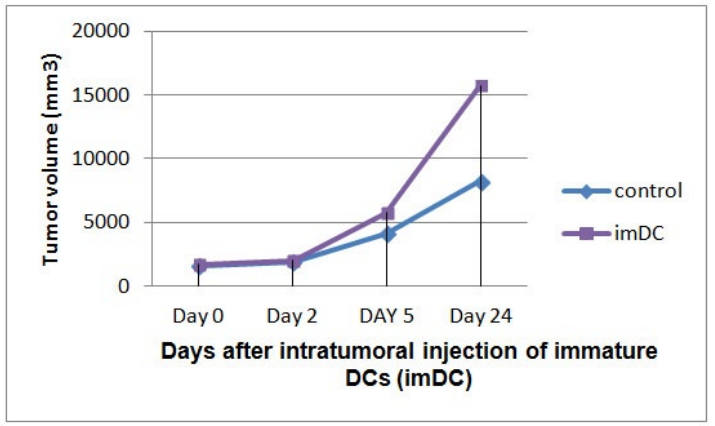

In vivo antitumor effects of DCs: Tumor growth rate was similar in mice received PBS, tumor cell lysates, or tumor cell lysatepulsed DCs matured with TNF-α. But, injection of antigen-unpulsed mature DCs 48 hour prior to tumor inoculation led to delayed tumor growth in 2 of 3 mice. Injection of immature DCs directly into the tumor tissue resulted in enhanced tumor growth when compared with tumor growth rate in mice of control tumor group (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Intratumoral injection of immature DCs directly into established tumor tissue resulted in enhanced tumor growth rate.

DISCUSSION

DCs with potent immunostimulatoy activity at the tumor sites are needed for efficient anticancer DC vaccine. Maturation and activation status of DCs robustly dictate immunostimulatory or immunoregulatory activities of DCs. Various maturation stimuli have been used to induce maturation in ex vivo generated DCs. In previous studies, a cytokine cocktail including TNF-α, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been used for maturation induction in DCs.16 However, these DCs failed to produce IL-12 and exhibited weak immunogenicity.17 Furthermore, in later studies PGE2 has been shown to induce interleukin-10 (IL-10) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These matured DCs were also capable of expanding regulatory T cells (Tregs),18,19 a major immunosuppressive cell type in cancer.20 Myeloid DCs generated in the presence of IL-1β, TNF-α, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), inter-feron-alpha (IFN-α), and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) showed high migratory activity and produced high levels of IL-12p70 (the founding member of IL-12). These DCs induced up to 40-fold higher numbers of melanoma-specific cytotoxic T cells when compared to DCs matured by IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and PGE2.21 Although maturation of human DCs with a combination of IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IFN-α, and poly I:C resulted in production of high levels of IL-12p70, however, this cocktail did not induce better T cell activation than the standard DC maturation cocktail.22 In our 8 days culture of DCs, TNF-α induced upregulation of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules on the cell surface of DCs. Tumor cell lysate-loaded DCs matured in the presence of TNF-α plus IFN-γ produced high levels of IL-12 in vitro while DCs matured in the presence of TNF-α alone produced low levels of IL-12. Thus, results emphasis that appropriate maturation stimuli should be used for induction of antitumor activity in ex vivo generated DCs.

In various murine tumor models, intratumoral injection of DCs retrovirally transduced with IL-12 gene led to regression of day 7 established tumors (eventual rejection in 2 of 5 tumors). In contrast, intratumoral injection of non-transduced DCs did not show significant antitumor effects. IL-12-transduced DCs could migrate to tumor-draining lymph node to the same extent as non-transduced DCs. Furthermore, intratumoral injection of IL-12-transduced DCs induced more tumor-specific Th1-type responses in regional lymph nodes and spleen than non-transduced DCs.23 In a mouse intracranial glioma model, intratumoral injection of interleukin-23 (IL-23)-transduced DCs induced effective antitumor immunity. Robust intratumoral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration, specific Th1-type response to the tumor in regional lymph nodes and spleen at levels greater than those of non-transduced DCs, and systemic immunity against the same tumor rechallenge were observed in animals received intratumoral injection of IL-23-transduced DCs.24 In our study, injection of antigen-unpulsed mature DCs two days before tumor inoculation resulted in antitumor effects while injection of immature DCs directly into the tumor tissue enhanced the tumor growth.

To explain these findings, it is important to know how ex vivo generated DCs affect tumors, and vice versa. In multiple murine T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and primary patient samples, tumor associated DCs were identified as a key cell type in the tumor microenvironment and these DCs were necessary and sufficient to support T-ALL survival ex vivo. 25 In transgenic adenocarinoma of mouse prostate model, tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid DCs expressed low levels of costimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86 and elevated levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). DCs isolated from prostate tumor tissues were able to tolerize peripheral blood T cells and microarray-based gene expression analysis showed that the tumor associated DCs express upregulated levels of genes associated with immune suppression such as IDO, arginase, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and forkhead box O3 (FOXO3).26

In some studies, tumor infiltrating DCs have been shown to have an immature phenotype with low expression of costimulatory molecules and incapable of inducing potent antitumor immune responses.27,28 In a murine ovarian carcinoma model, tumor progression was correlated with phenotypic changes in tumor-infiltration DCs from immunostimulatory to immunoinhibitory.29 Melanoma-derived factors suppressed expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and altered production of proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine by DC lines in vitro. 30 Melanoma-derived factors also altered maturation and activation of differentiated tissue resident DCs.31 In a lung metastasis model of melanoma, tumor-altered chemokine expression by lung-resident DCs correlated with increased lung infiltration by tumor-associated macrophages with M2 phenotype.31 Freshly isolated tumor cells could derive DCs to differentiate into immunosuppressive DCs expressing high levels of IL-10, nitric oxide (NO), VEGF, and arginase I.32

Recently, presence of immature DCs has been found to be associated with tumor growth and angiogenesis.33 In a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma, immature DCs contributed to ovarian cancer progression by acquiring a proangiogenic phenotype in response to VEGF secreted by engineered VEGF-A-expressing tumor cells.34 Immature DCs expressing VEGF-receptor 2 have also been contributed to the tumor angiogensis in a murine model of endometriosis and in the peritoneal Lewis lung carcinoma tumor model.35 DCs can help angiogenesis by producing factors that promote growth of endothelia cells.36 In addition, DCs participated in the generation of neovessels by interacting with endothelial cells and stabilizing newly expanded vasculature at the level of lymph nodes.37 On the other hand, DCs cultured in the presence of tumor derived factors showed some characteristics of endothelial cells suggesting transdifferentiation of DCs into epithelial-like cells.38,39

These findings indicate that tumor cells, tumor stromal cells, or tumor derived factors can dampen antitumor activity of DCs. On the other hand, DCs may encourage tumor growth by immunosuppressive activities or other effects such as promotion of tumor angiogenesis. Appropriate maturation induction in ex vivo generated DCs and manipulating the tumor microenvironment before DC vaccination may improve antitumor efficacy of DC vaccines.

CONCLUSION

For improving antitumor efficacy of DC vaccines it is important to understand how tumor and DCs influence each other. In several studies, tumor-associated DCs were immunosuppressive as they were unable to trigger tumor specific immune responses or they induced immunoregulatory cells expansion. Tumor-infiltrating DCs have also been related with tumor angiogenesis. Our results reveal that one of the main reasons why anticancer DC vaccines show limited successfulness in clinical trials may be adverse effects of the tumor microenvironment on DCs. It should be taken into account that DCs have a high plasticity, especially in the tumor microenvironment, and efforts must be done to improve their antitumor efficiency for example by optimal maturation of ex vivo generated DCs and reprogramming the immunosuppressive status of the tumor microenvironment.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ANIMAL CONSENT

In our study, we used female BALB/c mice for evaluation of antitumor effects of ex vivo generated DCs in vivo. The mice were housed in 12:12 h light-dark cycle with appropriate temperature and moisture and allowed for free access to food and water in the whole period of the study. This experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in Tehran University of Medical Science (Tehran, Iran).